What constitutes a ‘document’ and how does it function?

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the etymological origin is the Latin ‘documentum’, meaning ‘lesson, proof, instance, specimen’. As a verb, it is ‘to prove or support (something) by documentary evidence’, and ‘to provide with documents’. The online version of the OED includes a draft addition, whereby a document (as a noun) is ‘a collection of data in digital form that is considered a single item and typically has a unique filename by which it can be stored, retrieved, or transmitted (as a file, a spreadsheet, or a graphic)’. The current use of the noun ‘document’ is defined as ‘something written, inscribed, etc., which furnishes evidence or information upon any subject, as a manuscript, title-deed, tomb-stone, coin, picture, etc.’ (emphasis added).

Both ‘something’ and that first ‘etc.’ leave ample room for discussion. A document doubts whether it functions as something unique, or as something reproducible. A passport is a document, but a flyer equally so. Moreover, there is a circular reasoning: to document is ‘to provide with documents’. Defining (the functioning of) a document most likely involves ideas of communication, information, evidence, inscriptions, and implies notions of objectivity and neutrality – but the document is neither reducible to one of them, nor is it equal to their sum. It is hard to pinpoint it, as it disperses into and is affected by other fields: it is intrinsically tied to the history of media and to important currents in literature, photography and art; it is linked to epistemic and power structures. However ubiquitous it is, as an often tangible thing in our environment, and as a concept, a document deranges.

the-documents.org continuously gathers documents and provides them with a short textual description, explanation,

or digression, written by multiple authors. In Paper Knowledge, Lisa Gitelman paraphrases ‘documentalist’ Suzanne Briet, stating that ‘an antelope running wild would not be a document, but an antelope taken into a zoo would be one, presumably because it would then be framed – or reframed – as an example, specimen, or instance’. The gathered files are all documents – if they weren’t before publication, they now are. That is what the-documents.org, irreversibly, does. It is a zoo turning an antelope into an ‘antelope’.

As you made your way through the collection,

the-documents.org tracked the entries you viewed.

It documented your path through the website.

As such, the time spent on the-documents.org turned

into this – a new document.

This document was compiled by ____ on 13.09.2022 11:16, printed on ____ and contains 18 documents on _ pages.

(https://the-documents.org/log/13-09-2022-4363/)

the-documents.org is a project created and edited by De Cleene De Cleene; design & development by atelier Haegeman Temmerman.

the-documents.org has been online since 23.05.2021.

- De Cleene De Cleene is Michiel De Cleene and Arnout De Cleene. Together they form a research group that focusses on novel ways of approaching the everyday, by artistic means and from a cultural and critical perspective.

www.decleenedecleene.be / info@decleenedecleene.be - This project was made possible with the support of the Flemish Government and KASK & Conservatorium, the school of arts of HOGENT and Howest. It is part of the research project Documenting Objects, financed by the HOGENT Arts Research Fund.

- Briet, S. Qu’est-ce que la documentation? Paris: Edit, 1951.

- Gitelman, L. Paper Knowledge. Toward a Media History of Documents.

Durham/ London: Duke University Press, 2014. - Oxford English Dictionary Online. Accessed on 13.05.2021.

In Veurne, at the bakery museum, old speculaas moulds are presented in an almost religious fashion. Looking at these wooden blocks, they appear to be the negatives to Romanesque sculptures.

How does it feel to be conserved and showcased when your nature is to be a tool? What would it mean to re-use them, to fill those empty moulds, to shape something new without altering the matrix, to project what it would be like, to try out recipes and different baking, to learn from it and enjoy the results together? What scenes are even depicted? We lost part of their meaning, we could dig further, browse the books, ask our grandparents and collectively invent whatever narrative they might hold.

Clementine Vaultier’s interests, although trained as a ceramist, are in the warm surroundings of the fire rather than the production it engenders.

In John Berger and Jean Mohr’s groundbreaking book Another Way of Telling, the index at the end gives information on the images printed throughout the book. Most of them are Jean Mohr’s. In the section ‘If each time…’ – a wordless sequence of images which aims to develop an alternative way of telling a story – some images are referenced as ‘documents’. The information is sparse. On page 138, the index states, there is a ‘Document, detail’. It features a closeup of a knitted piece of fabric. It appears to be the same picture as seen on the first page of the section (p. 135), where it is printed beneath another image – a photo by Mohr of hands knitting. On this occasion, the image is indexed as ‘Document’.

Berger, J. & J. Mohr. Another Way of Telling. London / New York: Writers and Readers, 1982.

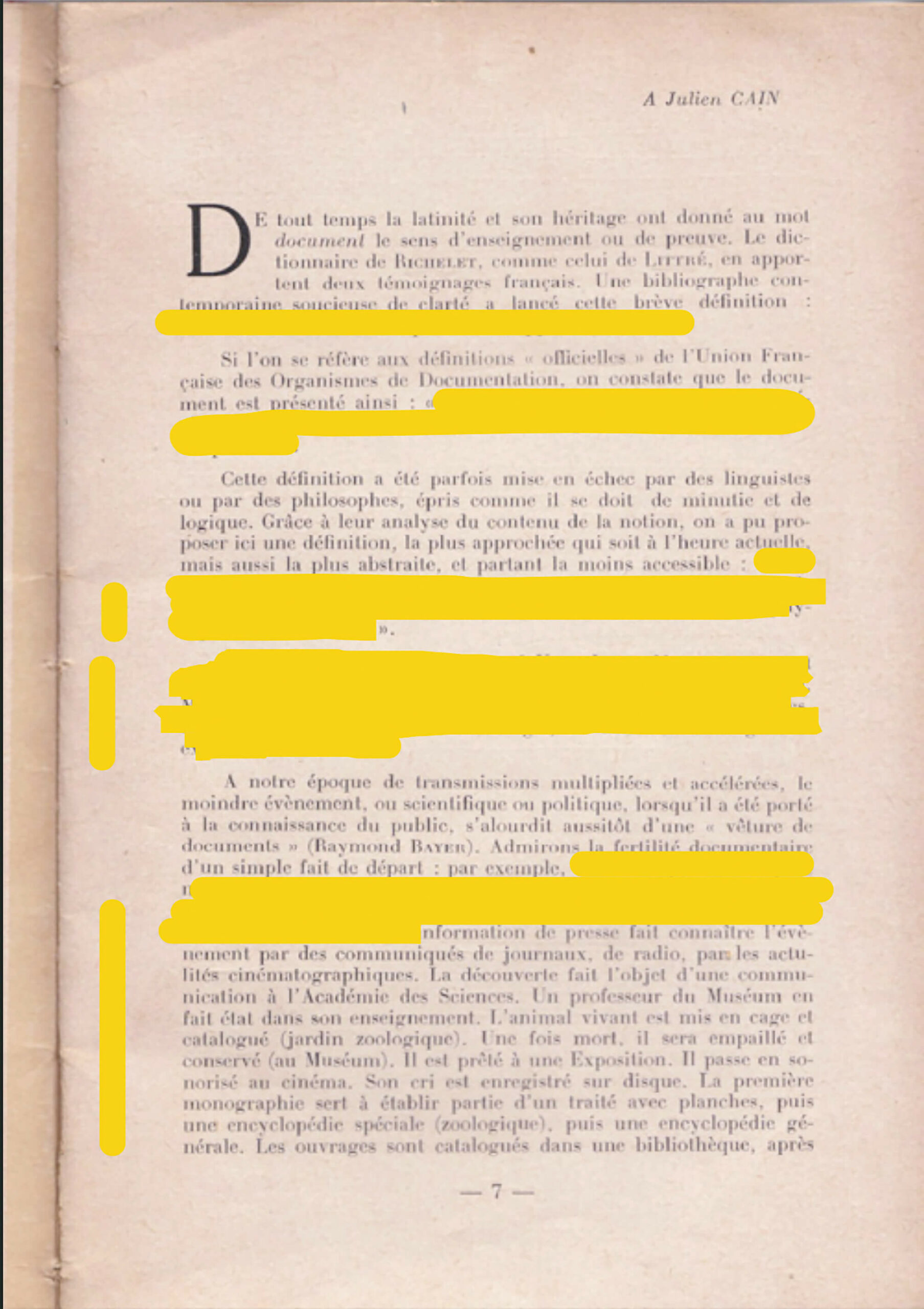

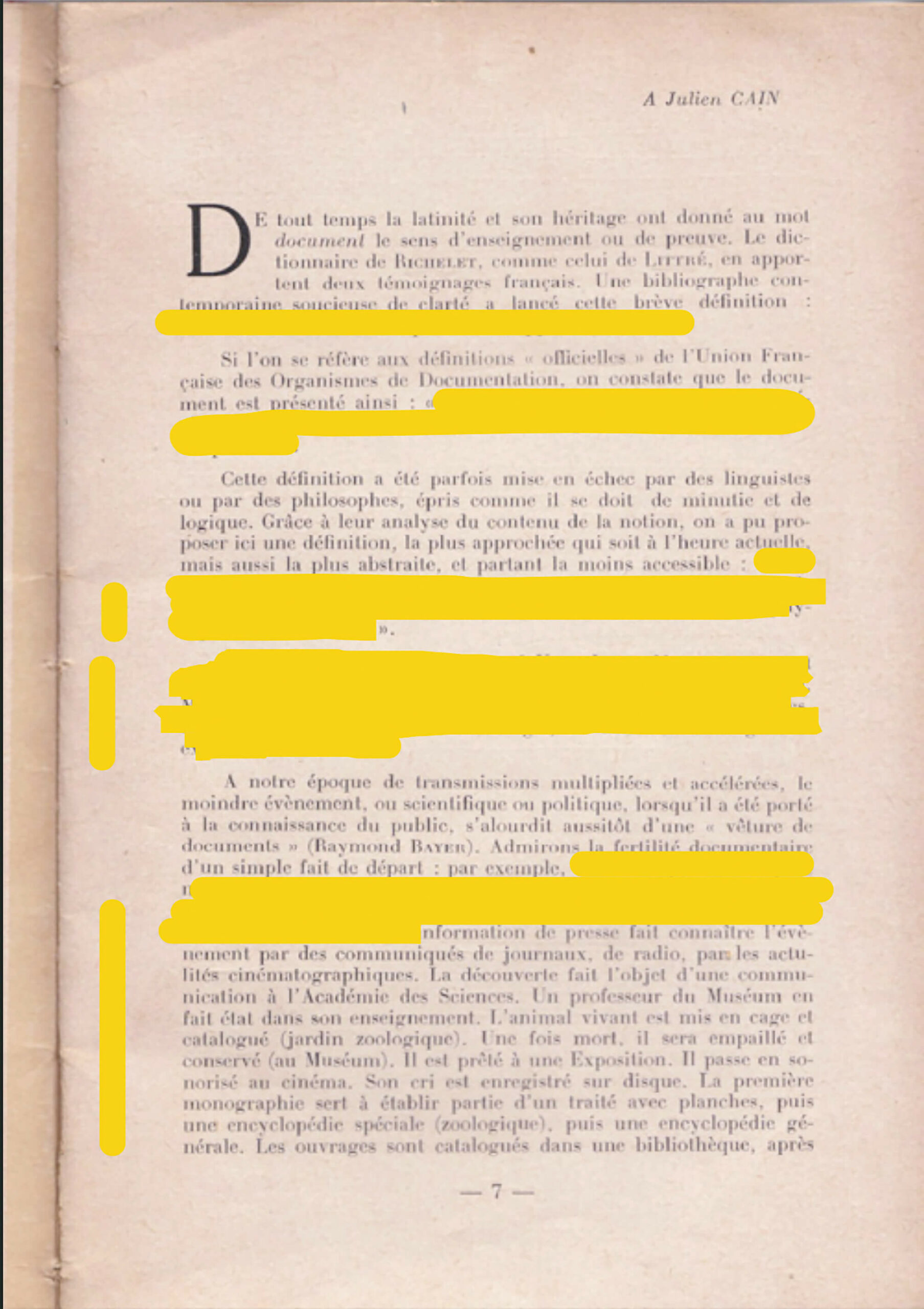

In the introduction to her book Qu’est-ce que la documentation?, French ‘documentalist’ Suzanne Briet asks what a document is. In a scrappy scan of her book I found online I am highlighting almost everything she writes. Is a star a document? Briet says it isn’t. But the catalogues and photographs of stars are. When I quickly opened the file with Apple’s ‘Preview’ application to check the above paraphrase, the highlighted sentences were illegible.

Briet is cited in Lisa Gitelman’s Paper Knowledge (2014).

Briet, S. Qu’est-ce que la documentation? Paris: Edit, 1951. Online: http://martinetl.free.fr/suzannebriet/questcequeladocumentation/briet.pdf

Depending on the language one chooses, the Wikipedia entry for ‘document’ shows a different picture. The French-language page shows what appears to be a Slovenian thesis written in 1984. The caption states it is a ‘book of Czechoslovak computer science author Květoslav Šoustal about computer networks’. The image was uploaded by Kelovy, a Slovakian mushroom-picker.

The anonymous hand rests on a lemon-yellow tablecloth, on which a yellow book and a blue binded file lie. The top left corner is the most intriguing, however: the tablecloth seems to be draped over a lemon, alongside a drinking glass. The cloth, however, does not get shaped by the lemon. Nor does the shadow-side of the lemon coincide with the shadow the other documents throw on the tablecloth. A closer look seems to indicate that the lemon is in fact an image of a lemon, printed on a plastic napkin.

The Russian wikipedia shows the image of a lease agreement. The German wikipedia for ‘document’ is text only.

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Document#/media/Fichier:KVETOSLAV_SOUSTAL_BOOK.JPG, created October 3, 2006 / original in original: paper, 1984

In the introduction to her book Qu’est-ce que la documentation?, French ‘documentalist’ Suzanne Briet asks what a document is. In a scrappy scan of her book I found online I am highlighting almost everything she writes. Is a star a document? Briet says it isn’t. But the catalogues and photographs of stars are. When I quickly opened the file with Apple’s ‘Preview’ application to check the above paraphrase, the highlighted sentences were illegible.

Briet is cited in Lisa Gitelman’s Paper Knowledge (2014).

Briet, S. Qu’est-ce que la documentation? Paris: Edit, 1951. Online: http://martinetl.free.fr/suzannebriet/questcequeladocumentation/briet.pdf

Ten years ago, in November, I drove up to Frisia – the northernmost province of The Netherlands. I was there to document the remains of air watchtowers: a network of 276 towers that were built in the fifties and sixties to warn the troops and population of possible aerial danger coming from the Soviet Union. It was very windy. The camera shook heavily. The poplars surrounding the concrete tower leaned heavily to one side.

I drove up to the seaside, a few kilometers farther. The wind was still strong when I reached the grassy dike that overlooked the kite-filled beach. I exposed the last piece of film left on the roll. Strong gusts of wind blew landwards.

Months later I didn’t bother to blow off the dust that had settled on the film before scanning it. A photograph without use, with low resolution, made for the sake of the archive’s completeness.

The dust on the film appears to be carried landwards, by the same gust of wind lifting the kites.

_44A6588.dng

At 13:26:43 I took a photograph of a concrete building without windows in an industrial zone just south of Brussels.

_44A6590.dng

At 16:46:15 I photographed a succession of office buildings in the same industrial zone.

_44A6589.dng

I must have walked about 1 kilometer between the concrete building without windows and the section of the industrial zone with the offices. At 13:43:49, the camera, safely stored in my backpack, recorded 0.4 seconds of the 20 minutes it took me to get there.

In The Snows of Venice, Alexander Kluge wonders whether he can take the liberty to conjure up what the sky looked like on 31 December 1799, as Schiller made his way to Goethe’s house. He goes on by saying that, historically, there’s a ‘LACK OF SENSORY ATTENTION AT CRUCIAL MOMENTS’.1 There are exceptions, though, like the cameraman that was sent out to document the fireworks on New Year’s Day 2000. The camera was turned on prematurely. The batteries were used up by midnight, but ‘certain gray tones, however, filtered through the cracks of its protective case, conveyed the motion of the walking cameraman, the transportation. The incompletely shut, low-information container was documented exactly […] To this day it provides inexact testimony as to the qualities of the leather of a twenty-first century carrying case and the precise sensitivity to light and dark demonstrated by a twenty-first century recording medium.’2

Lerner, B., Kluge, A. The Snows of Venice. Leipzig: Spector Books, 2018, p. 53

Ibid.

‘Because there is a kind of technological beauty to it.’

[…]

‘Yes, a perfect combination of the analogous on the one hand, and a kind of state of the art-futuristic cool on the other hand. It was elegant (unlike audio-cassettes), you could see the disc upon which your music was written (unlike the unfathomable MP3), it was less fragile than a CD(-R), and conveniently sized (you could hold it in the palm of your hand, slip it into your pocket). It had a kind of Mission Impossible-esque gadget feel to it. It had the aura of being permanently ahead of its time, but not in a far-fetched sci-fi kind of way. It was real.’

[…]

‘You mean the clicks. Yes, it had a sound of its own. A pleasant sound – the hard plastic hitting the hard plastic sleeve. The slidable, uhm, metal thing. The small read/write handle at the side. The small disc that was just a little bit loose. It – without being played – looked, felt and sounded like, like data, yes, like palpable data.’

[…]

‘Not any more.’

[…]

‘My uncle’s Elvis Costello This Year’s Model LP with way too little bass-sounds. Watching the detectives, to be precise.’

Robert Nemiroff and Jerry Bonnell’s lesser known project (R.N. and J.B. being the creators of Astronomy Picture of The Day), was making websites containing over a million of digits of square roots of irrational numbers, e.g. seven. ‘They were computed during spare time on a VAX alpha class machine over the course of a weekend. […] We believe these are the most digits ever computed for the square root of seven on or before 1 April 1994.’ Elsewhere, R.N. states: ‘They are not copyrighted and we do not think it is legally justifiable to copyright such a basic thing as the digits of a commonly used irrational number.’ If one wanted to get a copy of the 10 million digits of the square root of the number e R.N. and J.B. computed in their spare time, one can send an email to R.N. at nemiroff@grossc.gsfc.nasa.gov.

https://apod.nasa.gov/htmltest/gifcity/sqrt7.1mil

https://apod.nasa.gov/htmltest/rjn_dig.html

https://apod.nasa.gov/htmltest/rjn.html

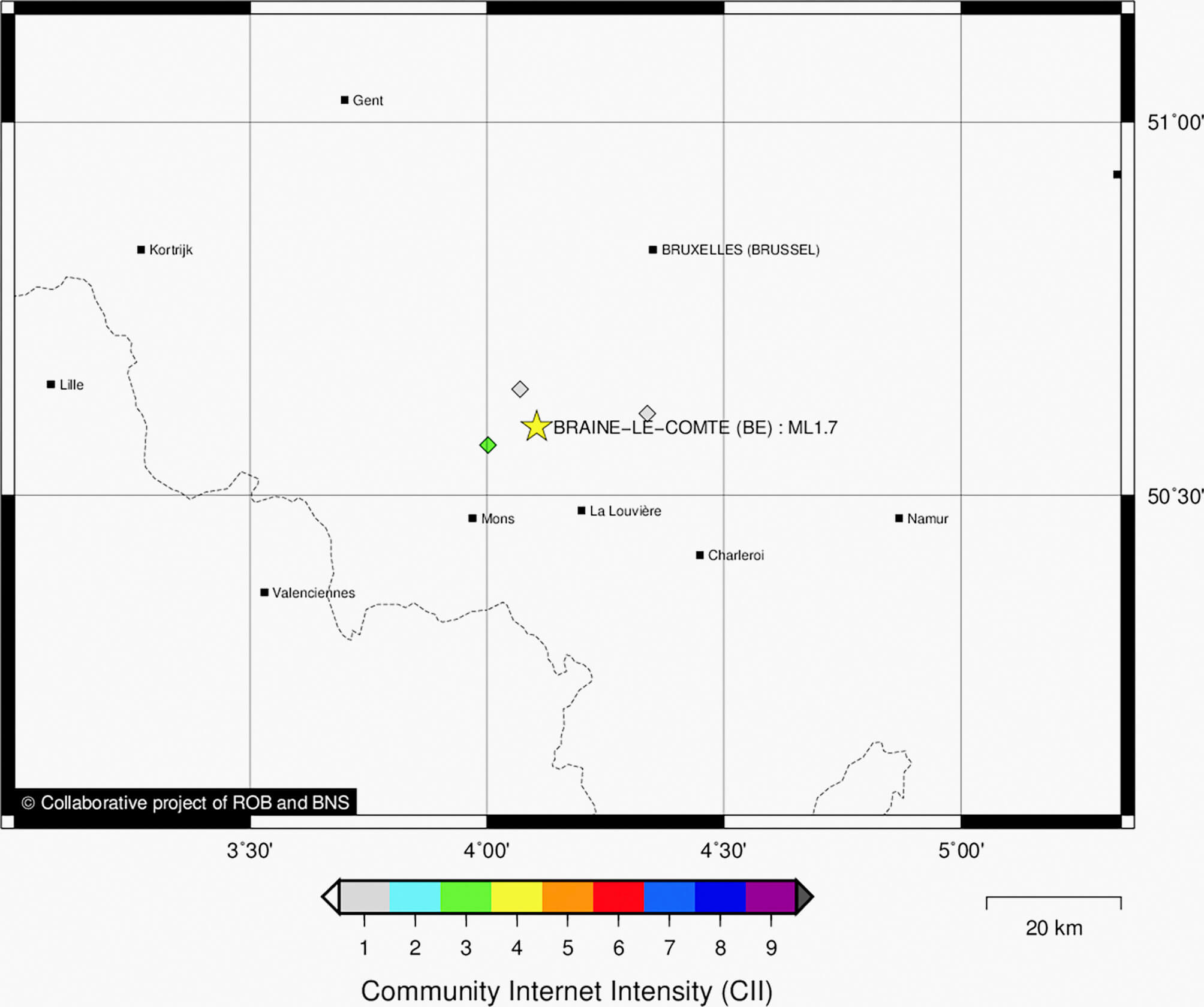

On May 6th 2020, 14h06 and 31 seconds, the Belgian Seismological Institute records an earthquake with a 1,7 magnitude in the region of Braine-Le-Compte. Three reactions from people in the neighbourhood, filed by the Institute, confirm the official seismological recordings. The Institute’s website classifies the earthquake as a ‘quarry blast’.

http://seismologie.be/nl/seismologie/aardbevingen-in-belgie/en130qj1o

The road down from the top of Mount Vesuvius, at Atrio Del Cavallo. The sun sets. The last tourist bus has headed down. Then the headlights of the guardian’s car swing their way down. It must be freezing. I am holding an orange-sized piece of petrified lava, probably stemming from the 1872 or 1944 eruption. A kilometer further down the road, the old Observatory is empty. Nowadays, monitoring seismic changes is done in a research centre in the city of Naples. Their seismographic registrations can be followed online, in real time. Two headlights swirling along the slopes, underneath me, are coming upwards.

A visit to the Royal Observatory of Belgium, in Ukkel. Most of the domes are damaged and need repairing. Only a few telescopes are in use. It is difficult to find a good spot from which to film the site. When we asked the people at the Royal Meteorological Institute – the Observatory’s neighbouring institution – if we could access their building’s roof to film the observatory, the answer was ‘no’.

I (M.D.C.) remember there was a fire nearby. We couldn’t see the flames, but a tall dark plume of smoke rose above the trees lining the site. We didn’t insist any longer and ceased our attempt to access the roof, hoping we might find a good spot to film the smoke with a dome in the foreground.

Kesteloot, J. Leerboek van Cosmografie voor Middelbaar en Lager Normaal Onderwijs (derde vermeerderde uitgave). Brugge: Firma Karel Beyaert, 1948.

The road down from the top of Mount Vesuvius, at Atrio Del Cavallo. The sun sets. The last tourist bus has headed down. Then the headlights of the guardian’s car swing their way down. It must be freezing. I am holding an orange-sized piece of petrified lava, probably stemming from the 1872 or 1944 eruption. A kilometer further down the road, the old Observatory is empty. Nowadays, monitoring seismic changes is done in a research centre in the city of Naples. Their seismographic registrations can be followed online, in real time. Two headlights swirling along the slopes, underneath me, are coming upwards.

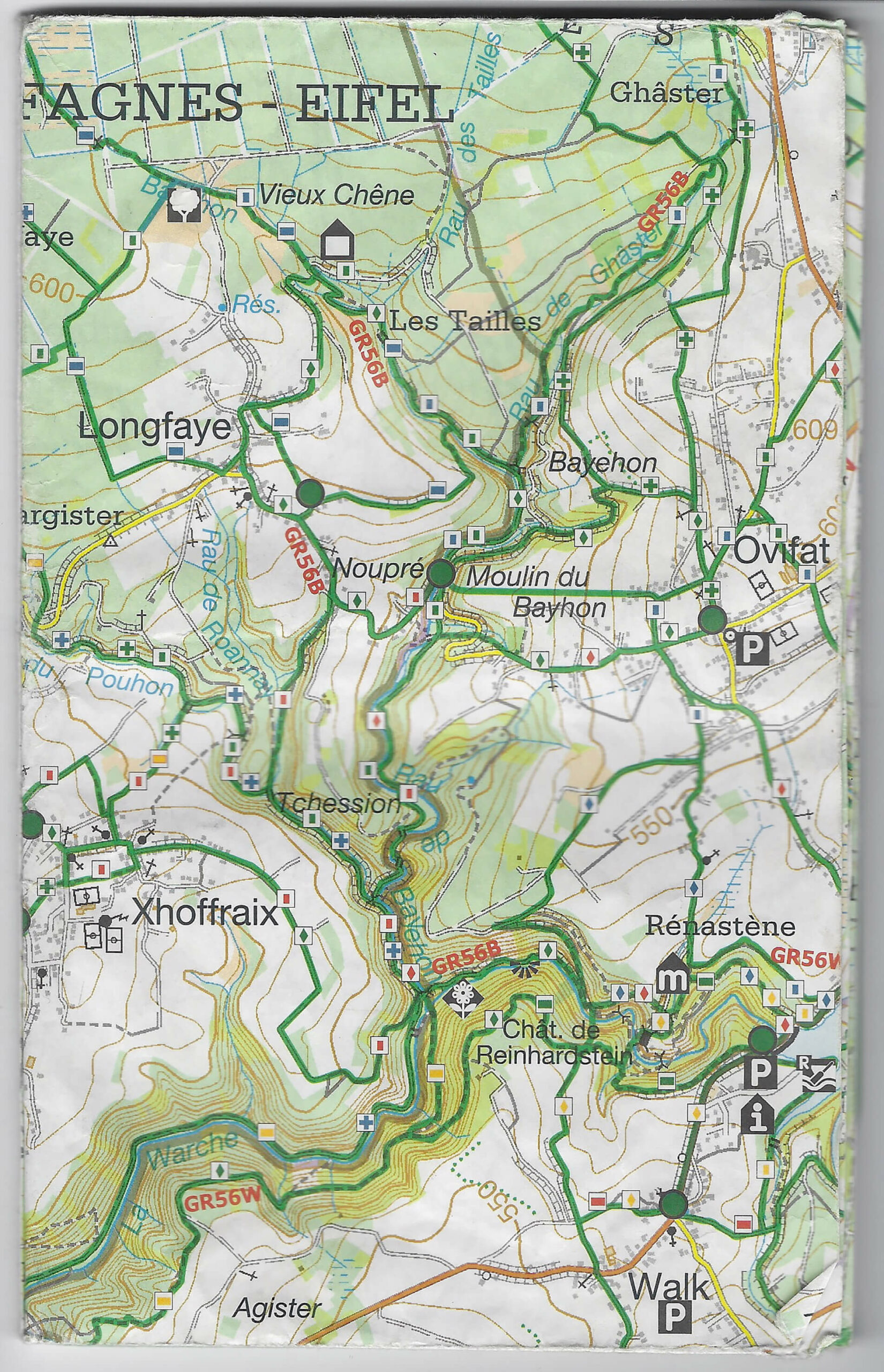

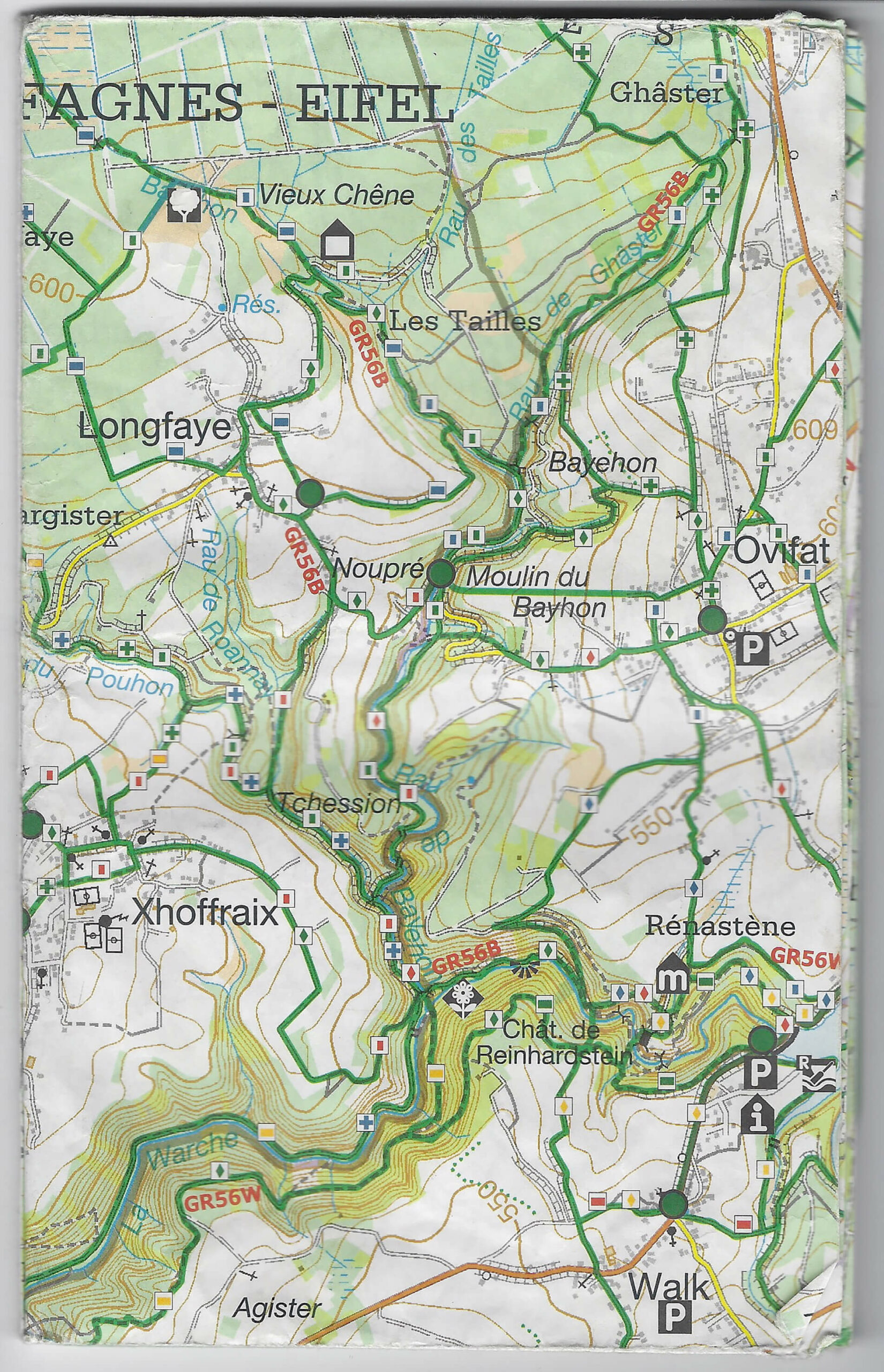

The paths in the valley of the Bayehon are covered with ice. We are making our way down towards the valley of the Ghâster. The temperature is minus 15 degrees Celsius. The water in our drinking bottles is frozen. We are betting on the shelter indicated on the map (Au Pied des Fagnes, Carte De Promenades, 1:25.000, Institut Geographique National) to pitch our tent. There is almost no wind, but every breath of air feels like we’re being hit with a thousand needles. What the map indicates as a shelter appears to be a picnic table.

Fairly detailed map of the two major marble quarries on the island of Tinos, Greece. The spontaneous route-advice was prepared by a local marble worker, P.D., in the Karia region of the island on a locally extracted, green marble slab. The waved lines represent roads traversing uphill, while the straight lines represent roads following a contour line of the topography.

‘Tell your friend that the wine is for girls; it’s very sweet,’ the marble worker alerted my travel companion K.S. after offering us local sweet wine. The workshop smelled like boiled meat and bones.

Notes on map from left to right, top to bottom:

- Towards Vathi

- Quarry

- incomprehensible

- Towards Vathi Bleu

- Isternia

- Pirgos

Márk Redele pursues projects that fundamentally relate to architecture and its practice but rarely look like architecture. www.markredele.com

The paths in the valley of the Bayehon are covered with ice. We are making our way down towards the valley of the Ghâster. The temperature is minus 15 degrees Celsius. The water in our drinking bottles is frozen. We are betting on the shelter indicated on the map (Au Pied des Fagnes, Carte De Promenades, 1:25.000, Institut Geographique National) to pitch our tent. There is almost no wind, but every breath of air feels like we’re being hit with a thousand needles. What the map indicates as a shelter appears to be a picnic table.

During the one day course Safety and Avalanches, teacher G.T. shows pictures of different manifestations of snow and ice. If one learns to read them, one can deduce the wind direction when hiking or skiing in mountainous terrain. Wind direction is crucial for assessing the stability of the snow. G.T.’s examples are of Austrian origin. He speaks about ‘Anraum’: displaced snow can get stacked horizontally against an object, such as a tree or a cross. The snow ‘grows and builds into the wind’. Counter-intuitively, the snow points to the side the wind is coming from. One can expect dangerous terrain in the direction of the ‘unbuilt’ side of the object.

Between the rhinos and the kangaroos in the Antwerp Zoo a wooden footpath curves through a grove of Sequoiadendron Giganteum trees. In the middle of this Californian forest, visitors find the giant slice of a felled tree of the same species. It was brought to the zoo in 1962 and was approximately 650 years old at the time. Eleven labels point out significant moments in history on the tree’s growth rings. They range from zoo- and zoology-related moments (for instance: ‘1901: The Okapi is described as a species’, or ‘1843: Foundation of the RZSA and opening of the Zoo’, or ‘1859: Darwin publishes The Origin of Species’, etc.), to cultural and historical milestones (‘1555: Plantijn starts publishing books in Antwerp’, or ‘1640: Rubens (baroque painter) dies’, or ‘1492: Columbus in America’). Another label points to the last growth ring and reads: ‘1962: this tree is felled and this tree disc is installed at the Zoo.’

The label pointing to the centre of the tree implies a simultaneity between the tree’s first growth year and the Battle of the Golden Spurs in 1302.

On closer inspection the slice seems to consist of two halves that were put together like a jigsaw puzzle. The resulting gap is skilfully patched with what appears to be wood from the same species – possibly even the same mammoth tree.