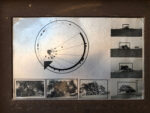

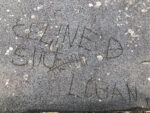

A document can function as something unique, or as something reproducible. A passport is a document, but a leaflet is equally so. Documents abound and vary: a photograph left as a bookmark in a second-hand book, a screenshot in the trash bin, a worn-out note on the pavement testifying to a school assignment and yesterday’s rain. But also a car recording the impact of a crash, a disappointing first photograph, a profanity carved in warm roofing, a slice of a mammoth tree representing historical events, a fragment of charred wood from a utility pole, a list of to-do’s written on the back of a hand. Defining a document involves ideas of communication, information, evidence, inscription, and implies notions of objectivity and neutrality – but the document is neither reducible to one of them, nor is it equal to their sum. Moreover, documents can lie; they can be ephemeral and subject to change. It is hard to pinpoint the document, as it disperses into and is affected by other fields: it is intrinsically tied to the history of media and to important currents in literature, photography and art; it is linked to epistemic and power structures. Despite its ubiquity, and however unwavering and stable it is considered to be, a document confuses.

the-documents.org aims to question what a document is and how it functions. It gathers documents and provides them with a caption – a short textual description, explanation, or digression. But as it collects documents, it also creates documents. In Paper Knowledge, Lisa Gitelman paraphrases documentalist Suzanne Briet, stating that ‘an antelope running wild would not be a document, but an antelope taken into a zoo would be one, presumably because it would then be framed – or reframed – as an example, specimen, or instance.’ The files gathered on the-documents.org are all documents – if they weren’t before publication, they now are. That is what the-documents.org, irreversibly, does. It is a zoo turning an antelope into an ‘antelope’.

Navigating the website can be done in different ways. There are links in the textual descriptions leading to other documents; there is a collection of all files published; at the right, the sidebar allows users to filter and arrange files based on themes, authors, types, etc. You can hit ‘random’. As the visitor makes his/her/their way through the collection, the-documents.org tracks the entries that have been viewed. It documents the path through the website. Your path can be saved digitally, printed at home, or ordered as a book. As such, the time spent on the-documents.org turns into a new document.

To get an email with updates when a new document is added, please leave your email address:

Contact: info [@] the-documents.org

The-documents.org is a project by De Cleene De Cleene; design & development by atelier Haegeman Temmerman.

This website uses cookies. By using this website you consent to the use of these cookies. For more information, please visit our Privacy Policy.

Arnout De Cleene & Michiel De Cleene combine a background in literature and photography with an interest in the document and the documentary. Topics vary. The poetics of blockchain. Mount Vesuvius’ 1872 eruption. Coppicing near a highway parking lot. An architect’s photographic archive. Etc. Research leads to artist books, as well as essays, lectures and exhibitions. They conduct research at KASK & Conservatory, School of Arts, Gent.

www.decleenedecleene.be

contact: info [@] decleenedecleene.be

This project was made possible with the support of the Flemish Government and KASK, the School of Arts of HOGENT and Howest.

Briet, S. Qu’est-ce que la documentation? Paris: Edit, 1951.

Gitelman, L. Paper Knowledge. Toward a Media History of Documents. Durham/London: Duke University Press, 2014.

Oxford English Dictionary Online. Accessed on 13.05.2021.

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,