What constitutes a ‘document’ and how does it function?

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the etymological origin is the Latin ‘documentum’, meaning ‘lesson, proof, instance, specimen’. As a verb, it is ‘to prove or support (something) by documentary evidence’, and ‘to provide with documents’. The online version of the OED includes a draft addition, whereby a document (as a noun) is ‘a collection of data in digital form that is considered a single item and typically has a unique filename by which it can be stored, retrieved, or transmitted (as a file, a spreadsheet, or a graphic)’. The current use of the noun ‘document’ is defined as ‘something written, inscribed, etc., which furnishes evidence or information upon any subject, as a manuscript, title-deed, tomb-stone, coin, picture, etc.’ (emphasis added).

Both ‘something’ and that first ‘etc.’ leave ample room for discussion. A document doubts whether it functions as something unique, or as something reproducible. A passport is a document, but a flyer equally so. Moreover, there is a circular reasoning: to document is ‘to provide with documents’. Defining (the functioning of) a document most likely involves ideas of communication, information, evidence, inscriptions, and implies notions of objectivity and neutrality – but the document is neither reducible to one of them, nor is it equal to their sum. It is hard to pinpoint it, as it disperses into and is affected by other fields: it is intrinsically tied to the history of media and to important currents in literature, photography and art; it is linked to epistemic and power structures. However ubiquitous it is, as an often tangible thing in our environment, and as a concept, a document deranges.

the-documents.org continuously gathers documents and provides them with a short textual description, explanation,

or digression, written by multiple authors. In Paper Knowledge, Lisa Gitelman paraphrases ‘documentalist’ Suzanne Briet, stating that ‘an antelope running wild would not be a document, but an antelope taken into a zoo would be one, presumably because it would then be framed – or reframed – as an example, specimen, or instance’. The gathered files are all documents – if they weren’t before publication, they now are. That is what the-documents.org, irreversibly, does. It is a zoo turning an antelope into an ‘antelope’.

As you made your way through the collection,

the-documents.org tracked the entries you viewed.

It documented your path through the website.

As such, the time spent on the-documents.org turned

into this – a new document.

This document was compiled by ____ on 15.12.2022 16:51, printed on ____ and contains 17 documents on _ pages.

(https://the-documents.org/log/15-12-2022-4908/)

the-documents.org is a project created and edited by De Cleene De Cleene; design & development by atelier Haegeman Temmerman.

the-documents.org has been online since 23.05.2021.

- De Cleene De Cleene is Michiel De Cleene and Arnout De Cleene. Together they form a research group that focusses on novel ways of approaching the everyday, by artistic means and from a cultural and critical perspective.

www.decleenedecleene.be / info@decleenedecleene.be - This project was made possible with the support of the Flemish Government and KASK & Conservatorium, the school of arts of HOGENT and Howest. It is part of the research project Documenting Objects, financed by the HOGENT Arts Research Fund.

- Briet, S. Qu’est-ce que la documentation? Paris: Edit, 1951.

- Gitelman, L. Paper Knowledge. Toward a Media History of Documents.

Durham/ London: Duke University Press, 2014. - Oxford English Dictionary Online. Accessed on 13.05.2021.

Coming back from holidays, we were waiting for the ferry to take us from Ramsgate to Ostend. We were well on time. As the ship entered the harbour, I asked my parents if I could take a photograph. It’s the first photograph I recall taking. I remember my dad telling me to wait long enough for the ship to get closer. I didn’t. I only got one try.1

It took a while before the film was developed. I couldn’t stop imagining what the photograph would look like: some picturesque waves in the foreground, the shining white ship, the red and blue text on the side, and a cloud filled sky.

Following every holiday, when we got home, the garden and our house would be photographed with the remaining exposures on the roll of film in the camera.

Depending on the perspective one chooses to look at the address, the house is adorned or not. The perspective from the main road is an image made in August 2020, the website (Google Maps) says. Our car is in front of the garage. It must be the end of August. We drive home from the hospital with the newborn, who doesn’t stop crying. Maybe I tightened the belts in the car seat too much. Arriving at our house, we see the slogans and decorations friends have hung at our front door. On the sill of the neighbour’s first floor window, there’s a brick that must have fallen from the second floor facade.

In between two cities along the Belgian coast, water has run from the dunes (and the Second World War Heritage site scattered among them), underneath the coastal road and tram rails, to the beach. It has formed a small S-shaped estuary, bound to disappear due to the increasingly harsh wind coming from the coast of Britain, blowing North-easterly, and hammering down on the levee. The vibrations of the empty Ostend-bound tram passing just before the photograph was taken, had no visible impact on the estuary.

Besides the scale indicating the length in centimeters, and the marks made by using it, a folding ruler displays other marks. These are the marks found on the weber broutin www.weber-broutin.be folding ruler, from left to right:

- 2m (in a frame, between 1cm and 2cm); indicating the total length of the folding ruler.

- a hexagon, barely visible, punched into the wood (between 2cm and 3cm); unknown signification.

- LUXMA (in a frame, between 4cm and 5cm); the manufacturer of the folding ruler (different from the company who ordered the folding ruler, their (the company’s, i.c. weber-broutin’s) name is printed on the sides of the ruler, and is only readable when the ruler is folded together for at least 50% (=1m).

- III (in an oval, between 6cm and 7cm); indication of the preciseness of the scale in centimeters, with ‘I’ in roman numbers meaning the most precise, and ‘IV’ in roman numbers meaning the least precise. (It is therefore not entirely certain that the ‘III’ on weber-broutin’s folding ruler can actually be found between 6cm and 7cm.)

- D 99 (in an oval, probably between 7cm and 8cm, see argument mentioned above); unknown signification.

- 1.1.60 (in an oval, probably between 7cm and 8cm, beneath D 99), signification unknown.

At the State Archive in Kortrijk, I am leafing through a 1955 photo album of the construction of the provisional church in Lokeren by the famous furniture company Kunstwerkstede De Coene. Gigantic wooden, prefabricated beams structure the building. It is cold. An old man in a grey suit shuffles between the racks to look up the date of birth of his great great grandmother. Snow covers the unfinished provisional roof. A bus passes, I reckon, through the pouring rain.

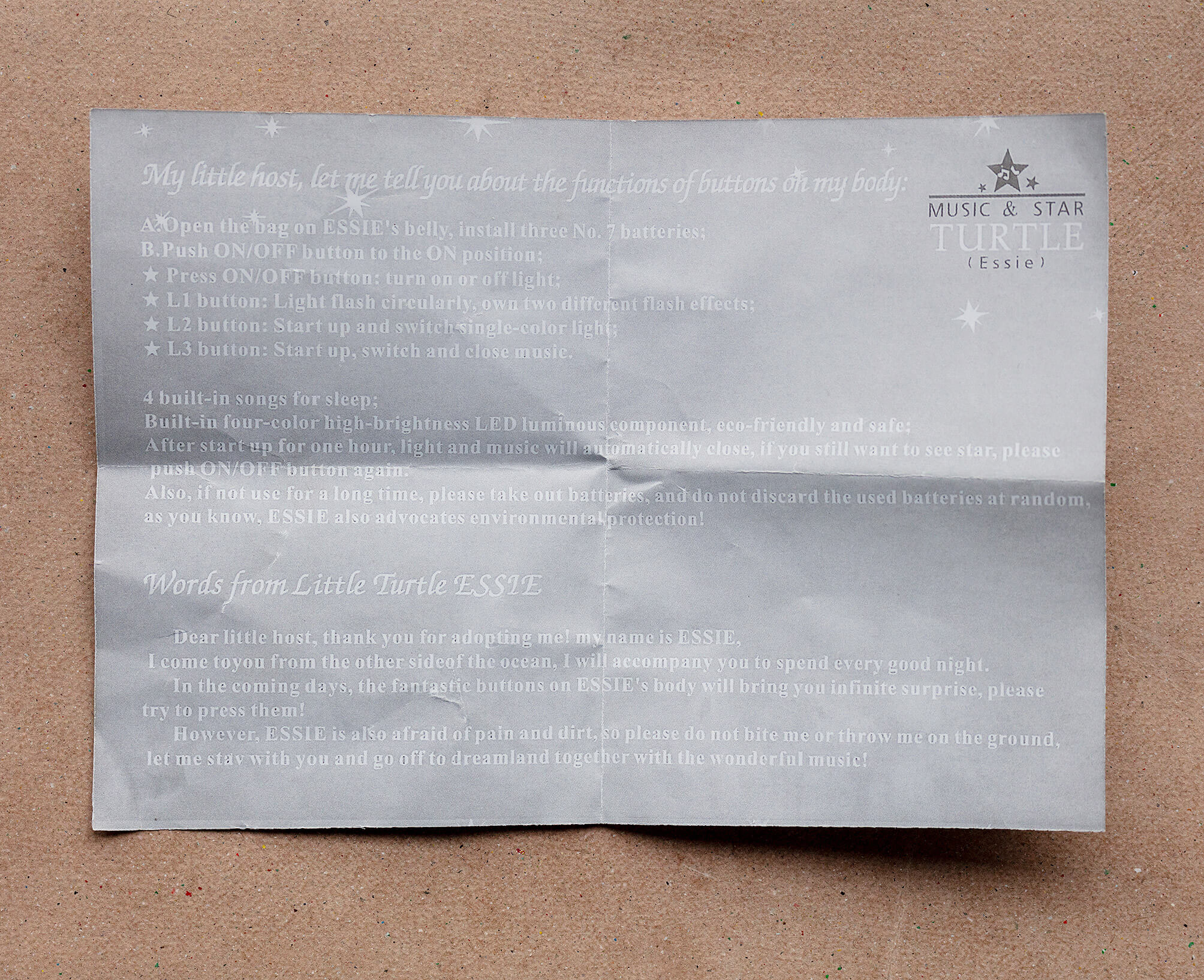

I bought my son a gift while abroad: a toy turtle named Essie whose perforated shield projects stars onto the ceiling in blue, green or amber. ‘8 actual star constellations’, the box proclaims.

The manual explains how to power up the turtle and what the four buttons on Essie’s back do. The small document (recto: Chinese, verso: English) concludes with some ‘Words from Little Turtle ESSIE’. In it the turtle shifts from direct speech to illeism1 and back.

The act of referring to oneself in the third instead of first person.

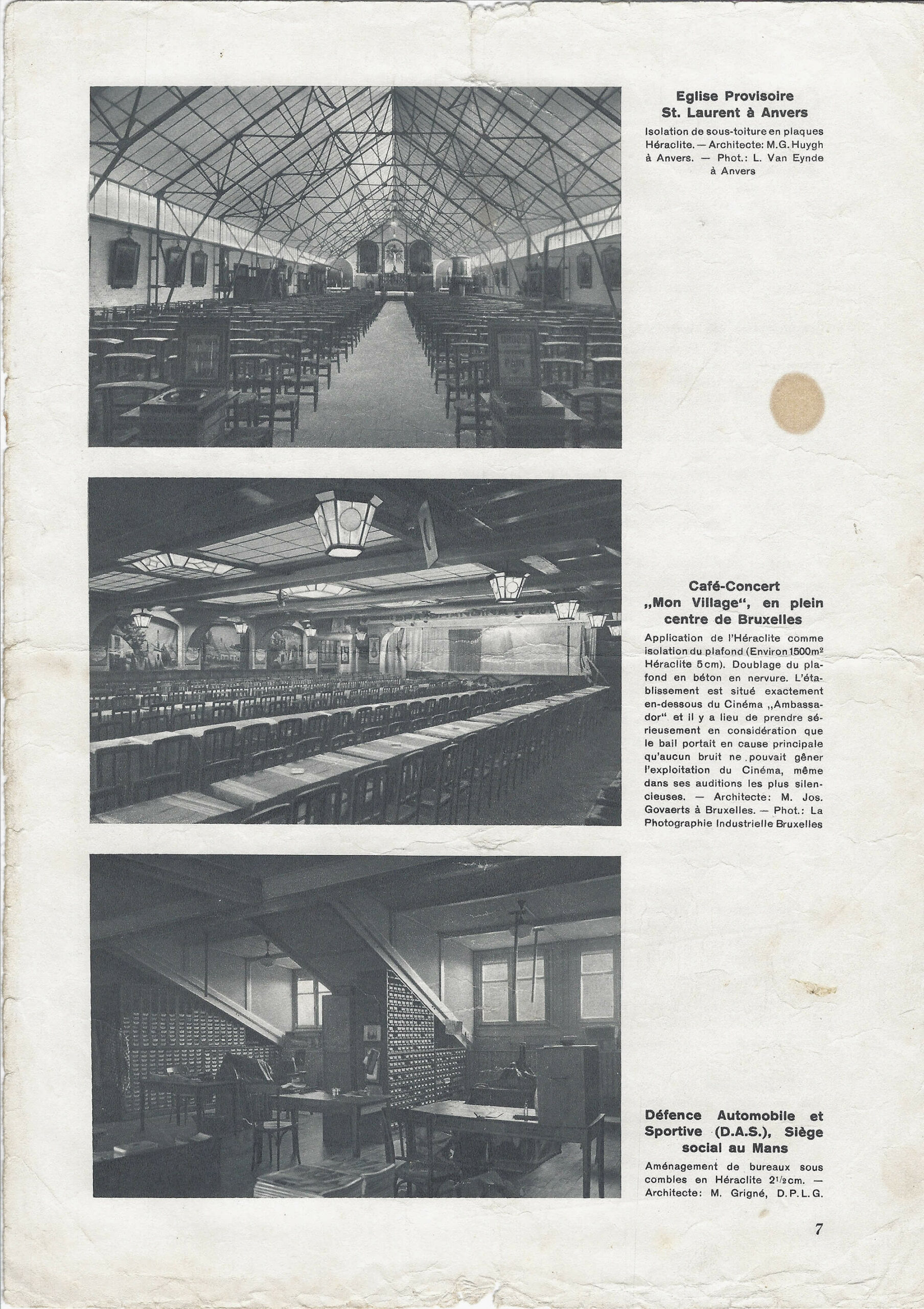

All chairs are empty, but all face something different. The bottom photograph shows empty chairs facing empty desks. In the middle picture, empty chairs face each other (underneath the inaudible sound of the cinema above). In the top photograph, the chairs seem to be facing the photographer. However, the altar’s in front of the photographer. He stands at the back of the provisional church. The chairs face the photographer and have turned their backs to the altar.

Revue Héraclite, 5 (1), april 1936, p. 7, paper, from the archive of architect O. Clemminck.

September 2020, three days before Neptune is in opposition, I meet Frédéric on top of a hill in Luxembourg.

Earlier that day he had sent me the coordinates of an airfield for remote controlled aeroplanes. He told me to meet him there at 20h. The airfield is situated on the top of a hill, granting a clear view of the horizon. Removed from highways and city centres, only the southern horizon lights up, where the Grand Duchy’s capital is located, some 15 kilometres farther. The weather is promising: ‘We might get a chance to see and photograph Neptune!’ he wrote.

I get there early. Frédéric is already setting up his tripod. Two elderly men are training for the perfect landing.

It is said that ‘if a space traveller were unfortunate enough to enter the atmosphere of one of the giant planets [such as Neptune], he or she would not find a single solid surface. Instead, as he or she descended into the planet, our traveller would find that the temperature, pressure, and density would all continue to increase smoothly, with no sharp transitions. Assuming that he or she was adequately protected from the temperature, pressure, and radiation, our traveller would eventually “float” at that level in the atmosphere where the surrounding density and his or her own density were equal.’1

It is said that it storms on Neptune.

Violently.

1200 mph.

They observed a great dark spot and called it: The Great Dark Spot.

It rains diamonds on Neptune.

Miner, E.D. & R.R. Wessen. Neptune. The Planet, Rings and Satellites. Chichester: Springer-Praxis, 2002, p. 18.

As the light of celestial objects travels through the Earth’s atmosphere, the various wavelengths that make up this light are refracted differently. This effect is called ‘dispersion’ and results in colour fringing on the edges of planetary discs: images with a sliver of blue at the top and a red one at the bottom appear.

When celestial objects are positioned close to the horizon (like Neptune when observed from Luxembourg) the images are severely affected: the path of the light through the atmosphere is longer, leading to greater dispersion.

For the same reason sunsets are red, Neptune turns from a monochromatic blue disc into a misaligned, multicoloured oval.

September 2020, three days before Neptune is in opposition, I meet Frédéric on top of a hill in Luxembourg.

Earlier that day he had sent me the coordinates of an airfield for remote controlled aeroplanes. He told me to meet him there at 20h. The airfield is situated on the top of a hill, granting a clear view of the horizon. Removed from highways and city centres, only the southern horizon lights up, where the Grand Duchy’s capital is located, some 15 kilometres farther. The weather is promising: ‘We might get a chance to see and photograph Neptune!’ he wrote.

I get there early. Frédéric is already setting up his tripod. Two elderly men are training for the perfect landing.

In Veurne, at the bakery museum, old speculaas moulds are presented in an almost religious fashion. Looking at these wooden blocks, they appear to be the negatives to Romanesque sculptures.

How does it feel to be conserved and showcased when your nature is to be a tool? What would it mean to re-use them, to fill those empty moulds, to shape something new without altering the matrix, to project what it would be like, to try out recipes and different baking, to learn from it and enjoy the results together? What scenes are even depicted? We lost part of their meaning, we could dig further, browse the books, ask our grandparents and collectively invent whatever narrative they might hold.

Clementine Vaultier’s interests, although trained as a ceramist, are in the warm surroundings of the fire rather than the production it engenders.

This video-still is taken from a documentary about ‘Le Coin du Balai – De Bezemhoek’, a Brussels neighborhood on the edge of the Sonian Wood. Historically, the inhabitants had the exclusive right to harvest young shoots of trees to make and sell brooms. In 1976, filmmaker Willy Biesemans captured the last broom-maker, still in possession of this vernacular knowledge.

Nowadays, the Sonian Wood is commonly understood as a place of natural beauty surrounding the city. The wood the forest produces is managed as a chain of production and sold in public auction to the best buyer. The bulk of the forest’s produce is exported abroad and eventually imported back as manufactured goods.

Clementine Vaultier’s interests, although trained as a ceramist, are in the warm surroundings of the fire rather than the production it engenders.

Biesemans, W. De Bezemhoek. 1976 (YouTube – De Bezemhoek)

For about an hour, he has been saying ‘owl’ at regular intervals. A cartoon character he picked up somewhere and is now fantasizing about, I guess. Or a Disney reference in one of the songs that have been playing on repeat all day, in the car, driving home from holidays.

50 kilometers further, I recognize the birds in the high-voltage pylons along the highway.

According to the amateur experts at hoogspanningsforum.com, these French pylons – used for conducting electricity from 63kV to 400kV – are nicknamed ‘chats’: the wiring can be interpreted as feline whiskers.

Some genera of owls, such as the Megascops or Screech owls, have whiskers.

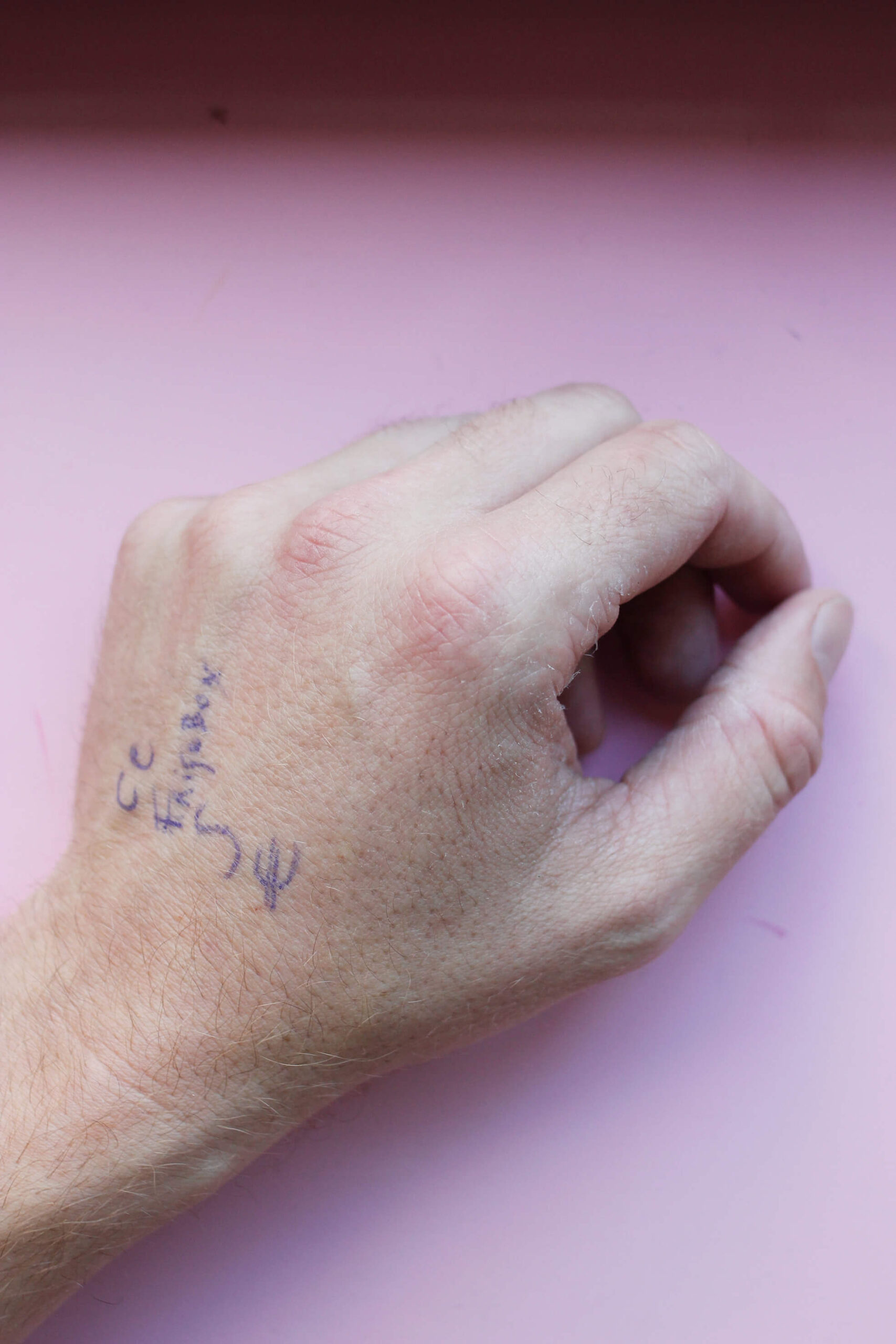

At the end of the day, riding home after work, I find a text on my hand:

C

D[…]ers

Desk

K

Communication book

‘Diapers’, I recall, and stop at the shop to buy them. Sweat, dust, and manic hand rubbing have rendered parts of the writing illegible. ‘C’ is for Carl, whose newborn I need to visit as soon as possible. Sometimes, I can’t remember what the initial stands for. I don’t have any friends with names beginning with a K (who have newborns I need to visit).

The right hand writes, the left hand serves as the canvas. The back of the right hand, folded around the pen, is blank and tells the always already written on back of the left hand, whose palm never holds a pen, what to register. Right: an author. Left: a poem, sunken into the pores.

Back home, I trace ‘Desk’ again, as not to forget to clean it tomorrow.

On Mondays, before noon, I go to the supermarket with my two-year-old son. After passing the lasagnes, the loaves of bread and the fruit and vegetables, we make a short stop at the aquarium with the lobsters. Around New Year, there are two of them.

After we’ve paid for the groceries and have put them in the car, we walk into the pet shop. We look at the parrots (Jacques, Louis and Marie-José), the rabbits, the guinea pigs, the assorted caged birds and the fish and turtles. He’s very fond of the Cyphotilapia Frontosa Burundi. He calls them zebras. They hail from Lake Tanganyika, the label says. It’s the second-oldest freshwater lake, the second-largest by volume and the second-deepest. The pet shop has adorned their aquarium with a scene of ocean waste.

In an effort to avert guilt, I look for something cheap and more or less useful to buy: birdseed, a snack for the neighbour’s cat, a comb for his grandparent’s Labrador, etc.

The GPS-plotter displays the ship near Keyhaven Lake, indefinitely. The sea appears calm, the horizon is level from one perspective.