What constitutes a ‘document’ and how does it function?

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the etymological origin is the Latin ‘documentum’, meaning ‘lesson, proof, instance, specimen’. As a verb, it is ‘to prove or support (something) by documentary evidence’, and ‘to provide with documents’. The online version of the OED includes a draft addition, whereby a document (as a noun) is ‘a collection of data in digital form that is considered a single item and typically has a unique filename by which it can be stored, retrieved, or transmitted (as a file, a spreadsheet, or a graphic)’. The current use of the noun ‘document’ is defined as ‘something written, inscribed, etc., which furnishes evidence or information upon any subject, as a manuscript, title-deed, tomb-stone, coin, picture, etc.’ (emphasis added).

Both ‘something’ and that first ‘etc.’ leave ample room for discussion. A document doubts whether it functions as something unique, or as something reproducible. A passport is a document, but a flyer equally so. Moreover, there is a circular reasoning: to document is ‘to provide with documents’. Defining (the functioning of) a document most likely involves ideas of communication, information, evidence, inscriptions, and implies notions of objectivity and neutrality – but the document is neither reducible to one of them, nor is it equal to their sum. It is hard to pinpoint it, as it disperses into and is affected by other fields: it is intrinsically tied to the history of media and to important currents in literature, photography and art; it is linked to epistemic and power structures. However ubiquitous it is, as an often tangible thing in our environment, and as a concept, a document deranges.

the-documents.org continuously gathers documents and provides them with a short textual description, explanation,

or digression, written by multiple authors. In Paper Knowledge, Lisa Gitelman paraphrases ‘documentalist’ Suzanne Briet, stating that ‘an antelope running wild would not be a document, but an antelope taken into a zoo would be one, presumably because it would then be framed – or reframed – as an example, specimen, or instance’. The gathered files are all documents – if they weren’t before publication, they now are. That is what the-documents.org, irreversibly, does. It is a zoo turning an antelope into an ‘antelope’.

As you made your way through the collection,

the-documents.org tracked the entries you viewed.

It documented your path through the website.

As such, the time spent on the-documents.org turned

into this – a new document.

This document was compiled by ____ on 11.03.2022 16:24, printed on ____ and contains 71 documents on _ pages.

(https://the-documents.org/log/11-03-2022-3907/)

the-documents.org is a project created and edited by De Cleene De Cleene; design & development by atelier Haegeman Temmerman.

the-documents.org has been online since 23.05.2021.

- De Cleene De Cleene is Michiel De Cleene and Arnout De Cleene. Together they form a research group that focusses on novel ways of approaching the everyday, by artistic means and from a cultural and critical perspective.

www.decleenedecleene.be / info@decleenedecleene.be - This project was made possible with the support of the Flemish Government and KASK & Conservatorium, the school of arts of HOGENT and Howest. It is part of the research project Documenting Objects, financed by the HOGENT Arts Research Fund.

- Briet, S. Qu’est-ce que la documentation? Paris: Edit, 1951.

- Gitelman, L. Paper Knowledge. Toward a Media History of Documents.

Durham/ London: Duke University Press, 2014. - Oxford English Dictionary Online. Accessed on 13.05.2021.

At the nuclear waste processing facility. While the photographer and the head of the communication department are making their way from the processing building to the temporary storage building, they walk past the central chimney.

‘On the highest of the accessible levels of the chimney, operators were finding small steel rings. They gathered them, but soon noticed that new rings were added. At a certain point at a rate of one ring a day.

[…]

It took them some time to realize what they were, so they started collecting them by slipping them onto a piece of rope. By now the rings on the rope span about this distance [spreads his arms to indicate a distance of about 1.2m].

[…]

They turned out to be rings that came from pigeon’s legs.

[…]

On top of our chimney resides a peregrine falcon.

[…]

I was told pigeon fanciers have a tendency to give a peregrine falcon – or any other bird of prey in their area – a hand at disappearing, but this one took up residency in the internal perimeter, where – as you know – access is severely restricted.’

First published in: De Cleene, M. Reference Guide. Amsterdam: Roma Publications, 2019

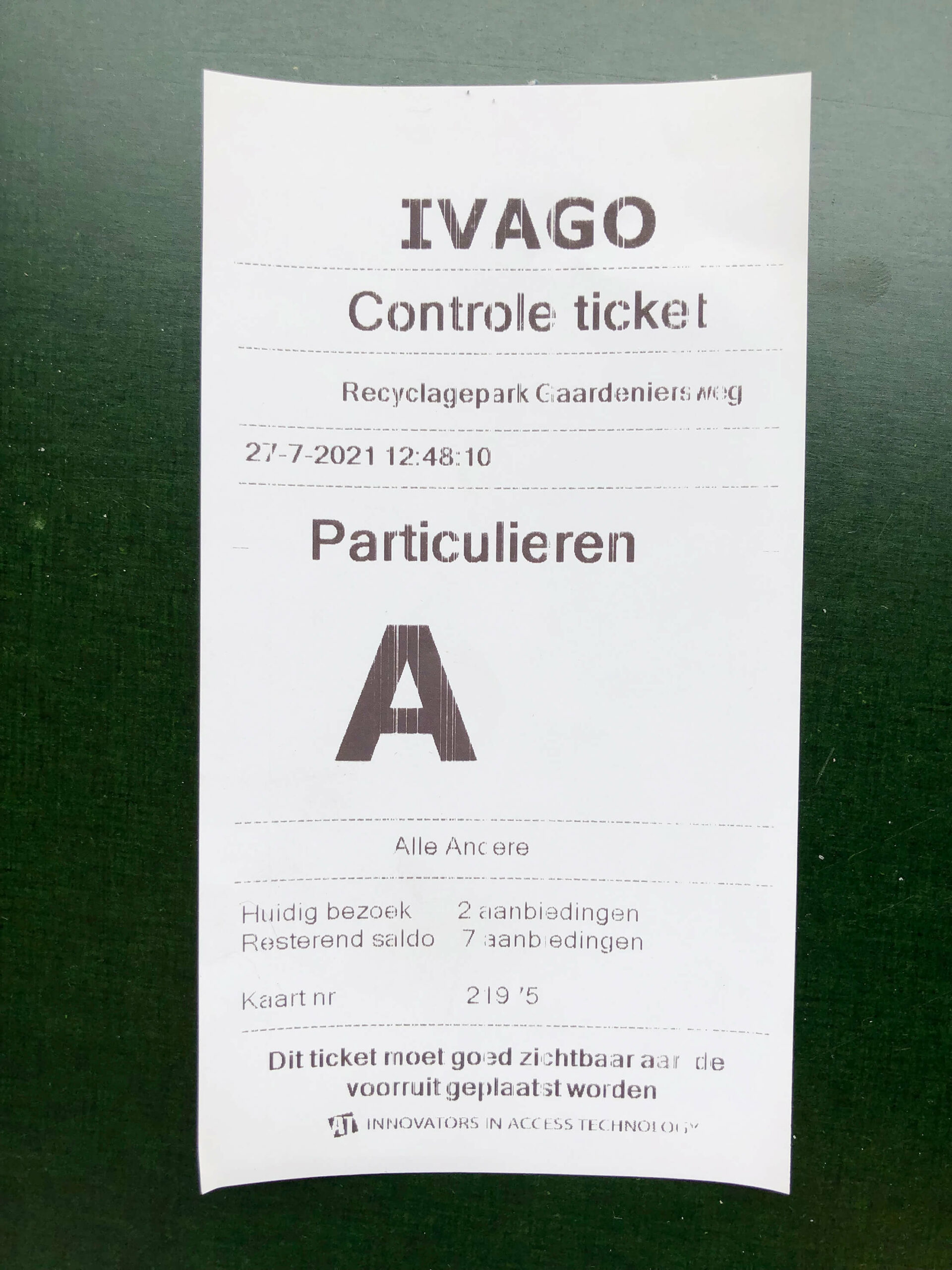

Today I brought an old bedspring, the styrofoam the air-humidifier came in, a few bags of sawdust and some scrap pieces of plywood to the municipal recycling center. As I was waiting to mount the stairs to the scrap metal container, a gray-haired man wearing blue leather shoes, dark jeans and a checkered shirt was tipping – with relative ease – a weight bench over the edge of the container.

‘You see?!’

[The man points at the waybill1 on the floor behind the glass door that closes off the abandoned and dismantled hall.]

‘It used to be here, I’m sure.’

[He looks around.]

‘I’m sure.’

[He turns towards me.]

‘Are you also here for the Leen Bakker?2 This used to be a Leen Bakker. I just looked it up on their website. They are open from 9 to 6 today.’

[He points at the waybill again.]

‘It was here. I remember well. It’s been years. But it’s here.’

[He walks away.]

‘I’ll look around.’

The waybill documents the transport of a 30m3 container filled with approximately 5000 kg of waste from this branch of Leen Bakker to a scrap processing company in nearby Ninove. They take care of scrap, both ferrous and non-ferrous metals. They also have a recognized depollution center for end-of-life vehicles.

A chain of furniture and interior stores with branches in the Netherlands, Belgium and the Caribbean part of the Kingdom of the Netherlands.

A block of concrete. Fissures are showing and rebar is sticking out from all sides. If it were still straight, the block would measure approximately 130 x 15 x 40cm.

It is lying by the side of the road, a few hundred meters from a construction site. It appears to be shaped by impact. Maybe the block plummeted to the ground from a great height. Perhaps, something heavy hit it. For all one knows, it served as a column and was exposed to an unforeseen amount of pressure, causing it to buckle.

According to Eyal Weizman ‘[a]rchitecture emerges as a documentary form, not because photographs of it circulate in the public domain but rather because it performs variations on the following three things: it registers the effect of force fields, it contains or stores these forces in material deformations, and, with the help of other mediating technologies and the forum, it transmits this information further.’1

Weizman, E. ‘Introduction’, in: Forensic Architecture. Forensis. The Architecture of Public Truth. London/Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2014.

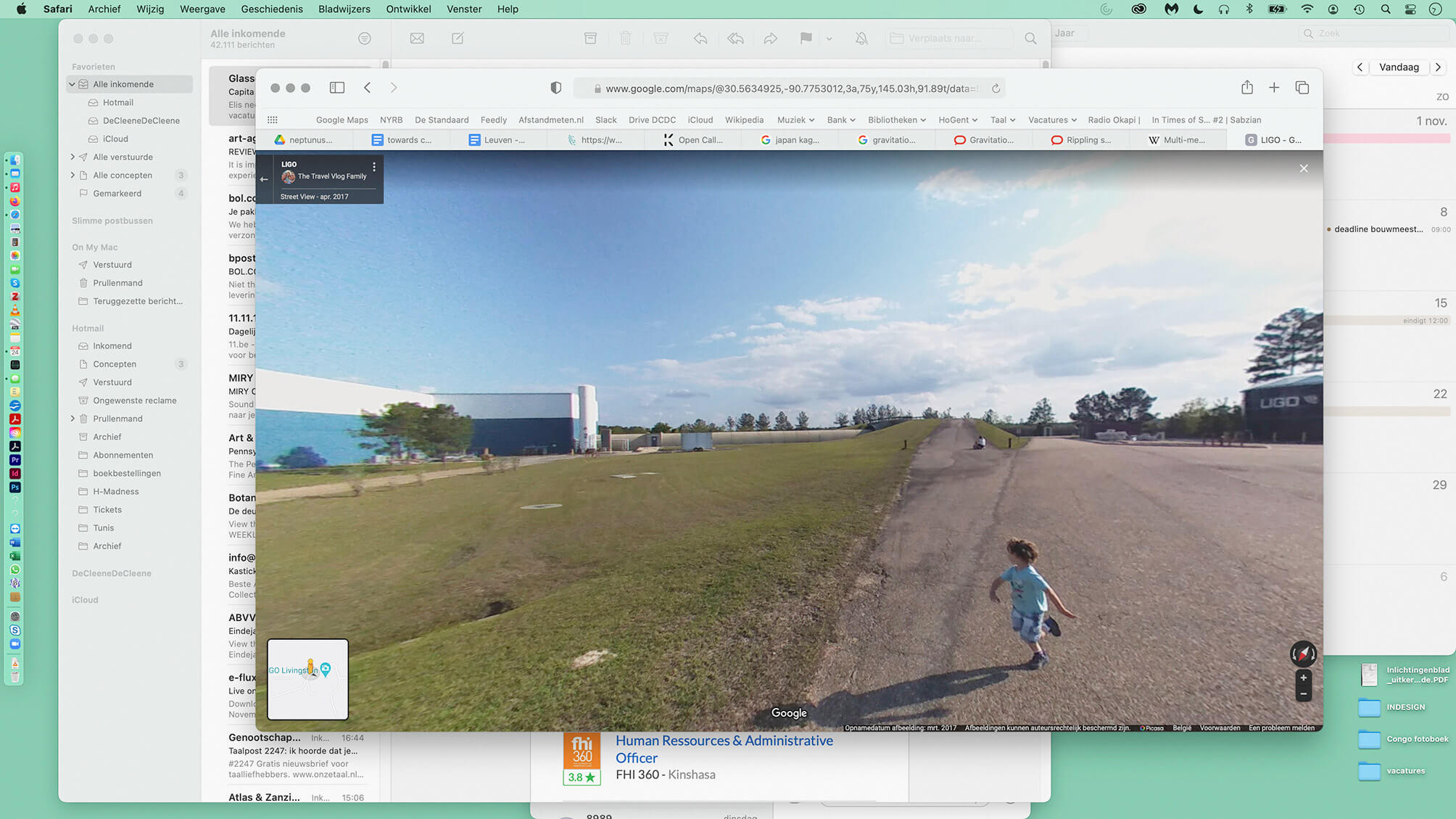

To detect gravitational waves, physicists built enormous research centers, amongst others at Livingston, Louisiana. The facility mainly consists of two tunnels in an L-shape. Mirrors inside provide data. Disturbances from gravitational waves are miniscule. To prevent interference from outside, such as vibrations caused by people passing in the neighbourhood, the mirrors have to be detached from the earth. They ‘float’, suspended by glass fibers in a pendulum-like construction. As I was watching my screen, a courier was on his way to deliver a book (Noel-Todd, J. The Penguin Book of the Prose Poem: From Baudelaire to Anne Carson. London: Penguin, 2019).

On the online thrift shop 2dehands.be the homepage generates a ‘for you’ section. On November 9th this section listed, among other things, a picture of the sky on a patch of concrete. On closer inspection, it became clear that it was the sky’s reflection in a mirror with a red frame and four lightbulbs in it, the kind you might see at the hairdresser’s or backstage in a television studio or theatre. The seller estimates the mirror’s current value to be 45,00 EUR. The listing includes five photographs. In the fifth one, the object for sale reflects a bucolic landscape: a blue sky, white clouds, some trees and a fragment of a barn.

I recognized it in a flash, the late Jurassic-early Cretaceous herbivore looming dangerously over the road I was cycling on. I thought of Some Windy Trees.1

A utility pole (425638, 07/99, 07/2002, COBRA), electrical wires, a hawthorn (Crataegus) and an old man’s beard (Clematis vitalba). A symbiosis.

Delbrouck, V. Some Windy Trees. Loupoigne: Wilderness, 2013.

On the second to last day of a research visit at CERN, there was some spare time in the schedule. I took a long walk towards building 282 in search of some excavation samples: cylindrical pieces of rock that were preserved when the tunnel was dug, glued to a block of wood and frequently exhibited in museums over the last three decades as material evidence of the earthwork and as a witness to the depth. The route led me along the back of building 363 where the wind caused young trees – now gone – to scuff the facade over time.

First published in: De Cleene, M. Reference Guide. Amsterdam: Roma Publications, 2019, as W.569.EXC CERN, Towards Building 282, in search of excavation samples

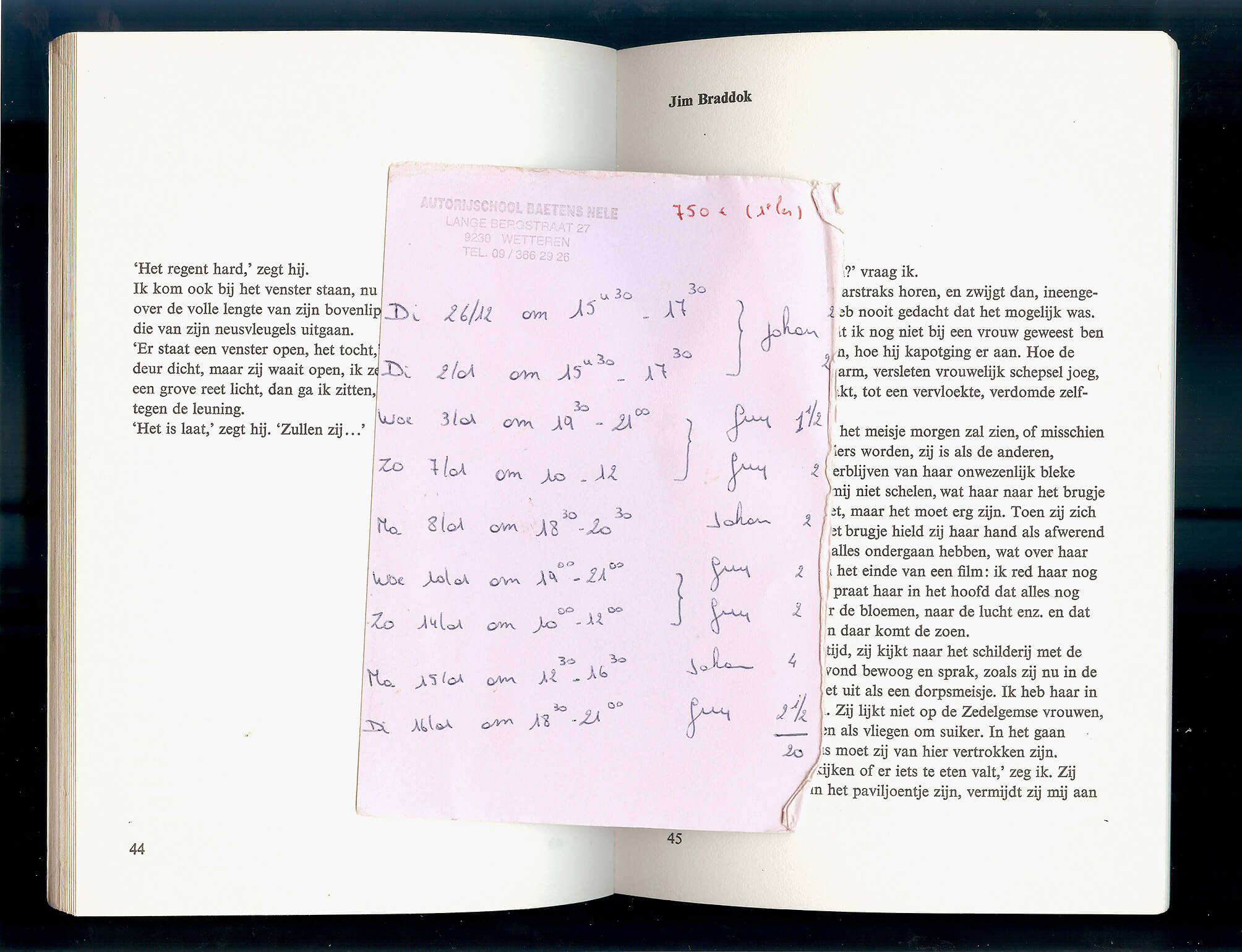

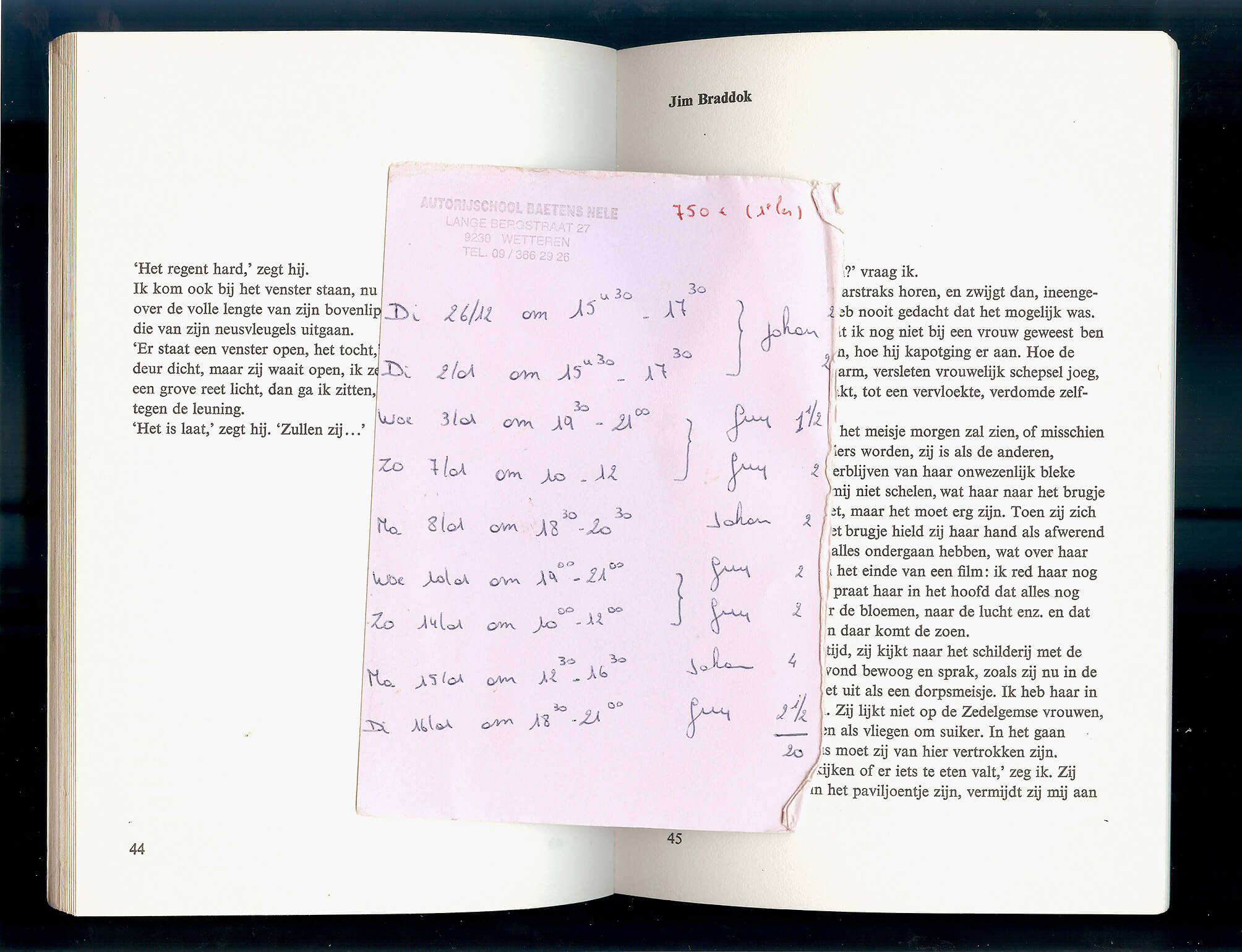

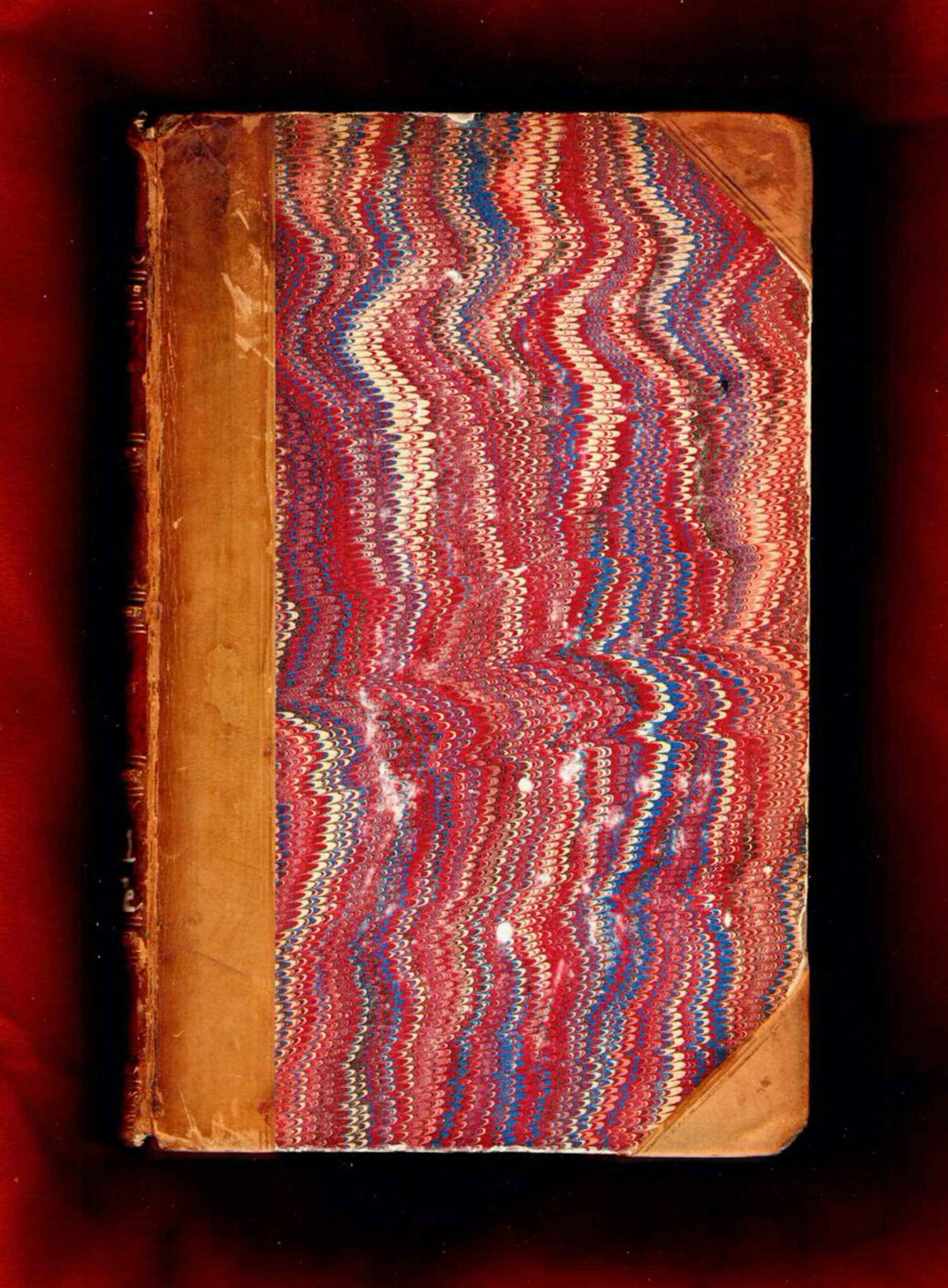

In his debut novel ‘De Metsiers’ Hugo Claus employs a multiple narrative perspective. In the copy I picked up in a thrift store, there’s a bookmarker between pages 44 and 45 where the perspective shifts from Ana to Jim Braddok. It’s pouring. The pink piece of paper lists 9 sessions at a driving school. There’s a total of 20 hours, taught alternately by Johan and Guy.

In 2000, 2006 and 2017 the twenty-sixth of December was a Tuesday. (Earlier years are improbable, since the Euro was not introduced yet.)

Claus, H. De Metsiers. Amsterdam: Uitgeverij De Bezige Bij, 1978.

‘ORIGINAL. Rire de tout ce qui est original, le haïr, le bafouer, et l’exterminer si l’on peut.’

[‘ORIGINAL. Laugh with everything that’s original, hate it, scold it, exterminate it if you can.’]

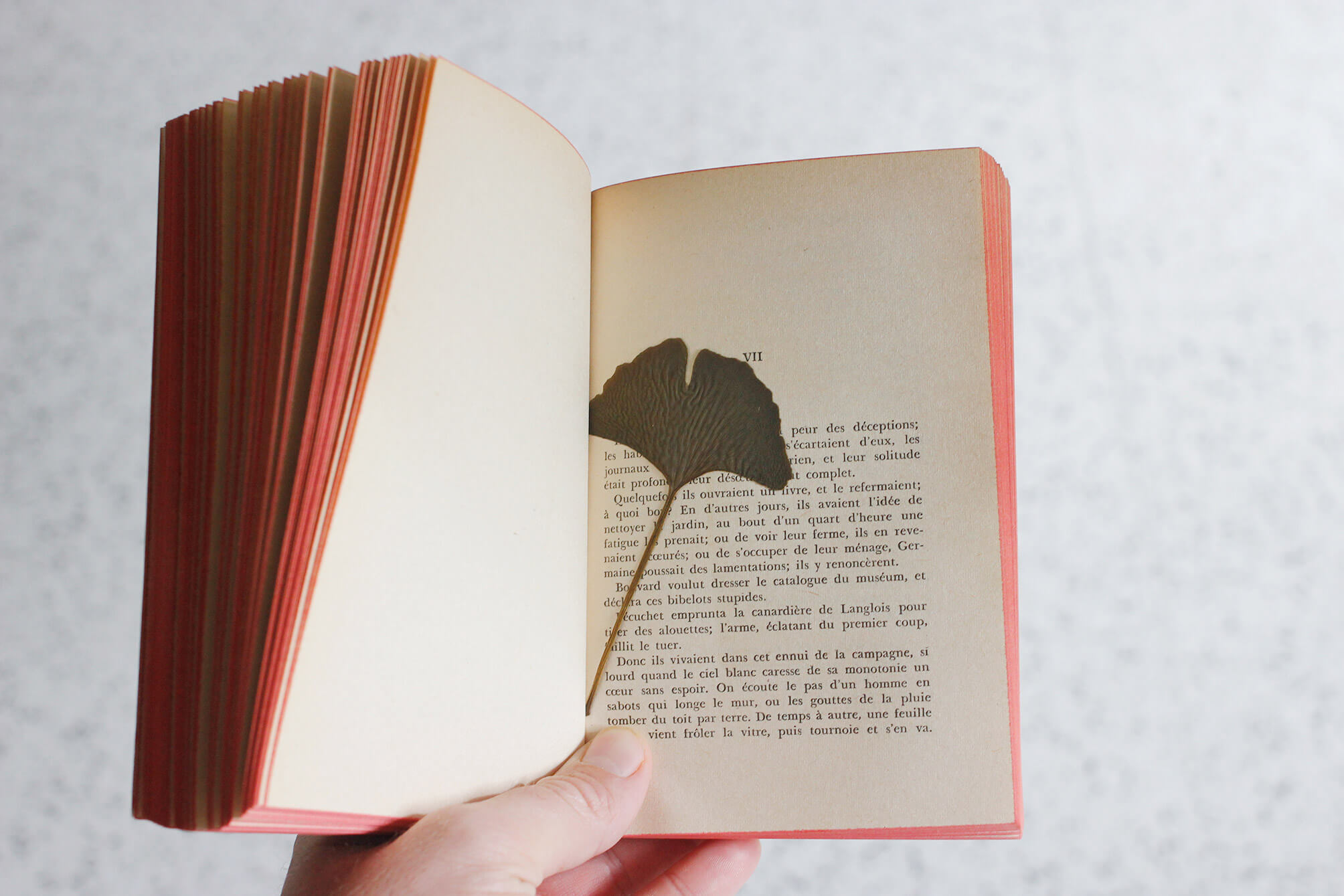

Flaubert. Bouvard et Pécuchet (présenté par Raymond Queneau). Paris: Livre de poche, 1959 (with p. 232-233: dried leaf of a ginkgo tree, and p. 324-325: dried leaf of a birch tree), p. 429 [2,00 EUR, Librairie Vic-sur-Cère, August 2021].

On Wednesday, May 9, 2018 at 2:23:14 PM Koh Elaine starts the thread original or original copy on the The Free Dictionary by Farlex’s forum.

‘Is “original copy” correct or should it be “original”? Thanks.’

The seventh reply to Elaine’s question is Wilmar’s on Thursday (his was preceded by towan52, georgew, NKM, Koh Elaine, Sarrriesfan, ChrisKC, Ashwin Joshi).

‘An original copy IS the original.

Folks usually call the document first created the original, but some will say original copy. If I run that original thru the copy machine, I end up with two copies (yes, I said copies) of the same thing – the original and the duplicate of it (in terms of content). This is how the term is commonly used.

If your writing or conversation depends heavily on understand the difference, I would recommend using the terms original and duplicates. There are many times when that is very important, in that the original must be retained by a particular party, and the duplicates are marked as such and distributed or stored as required depending on the document and the circumstance.

If you are just trying to make sure that you have enough copies to distribute to everyone at the company meeting this afternoon, use whatever terms trips your trigger. But, if you want to ensure that you keep custody of the original, so that you can make additional duplicates (copies) when additional people attend, then be more specific about the words you use.

OH, and, please, in the future, include some context with your question. Asking if “word” is correct doesn’t go very far in supplying a reasonably useful response.’

https://forum.thefreedictionary.com/postst182102_original-or-original-copy.aspx

Our one year old’s favourite toy he’s not supposed to play with is the HP Officejet Pro L7590 All-in-one in my office. I have given up on forbidding him to play with it. We have a new game: he brings me one of his other toys, we put it on the flatbed, close the lid – as far as possible –, press the button ‘START COPY – COLOR’ and wait for the print to come out of the machine. When we place the original onto the copy, he laughs. So far we have copied his blue pacifier, his planet-earth-bouncy-ball and his rattling crocodile.

At the copyshop, on a shelf above photocopier 8, the lid of a box of paper serves as the container for ‘forgotten originals’.1

The book being copied: Didi-Huberman, G. La ressemblance par contact. Archéologie, anachronisme et modernité de l’empreinte. Paris: Les Editions de Minuit, 2008.

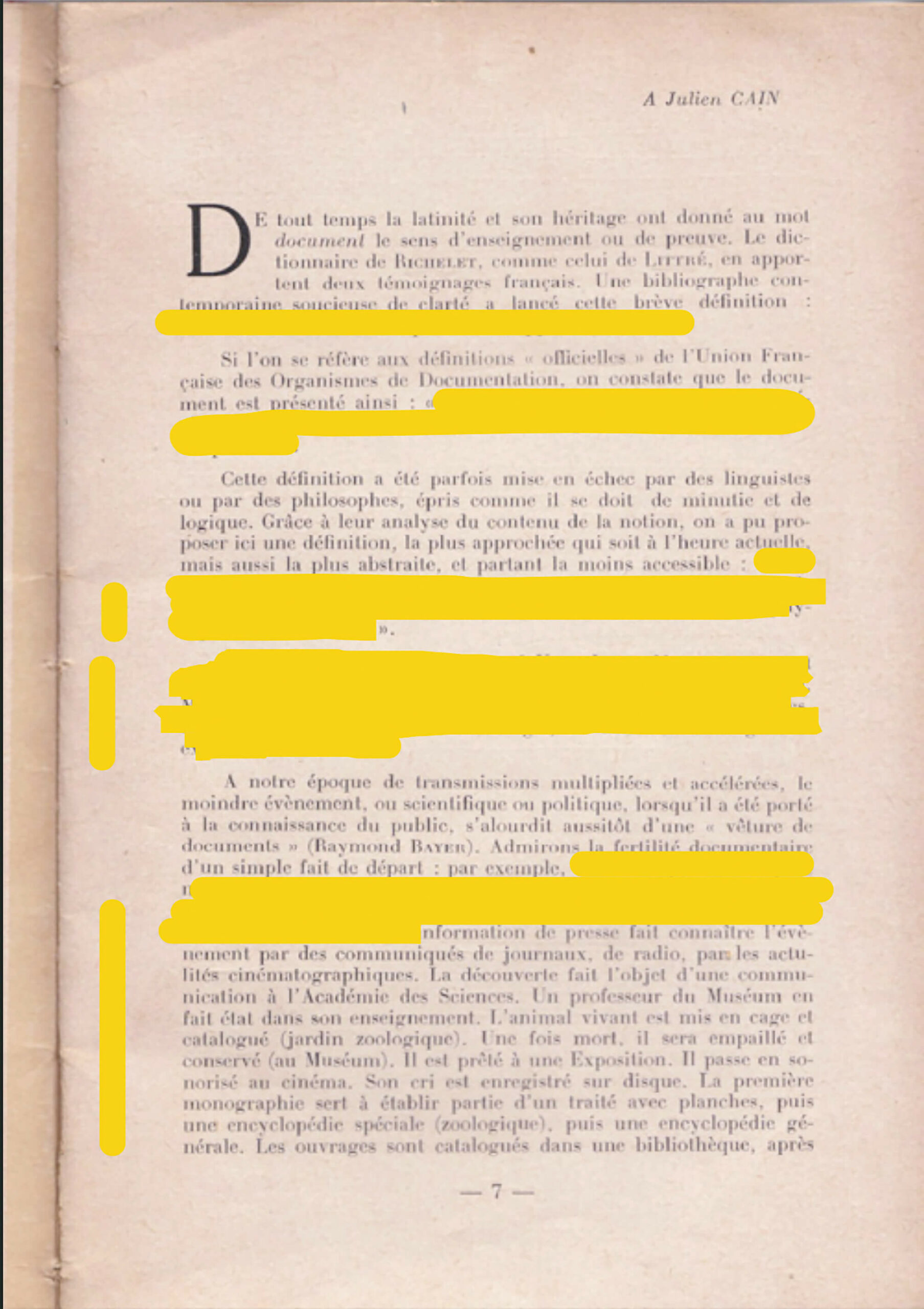

In the introduction to her book Qu’est-ce que la documentation?, French ‘documentalist’ Suzanne Briet asks what a document is. In a scrappy scan of her book I found online I am highlighting almost everything she writes. Is a star a document? Briet says it isn’t. But the catalogues and photographs of stars are. When I quickly opened the file with Apple’s ‘Preview’ application to check the above paraphrase, the highlighted sentences were illegible.

Briet is cited in Lisa Gitelman’s Paper Knowledge (2014).

Briet, S. Qu’est-ce que la documentation? Paris: Edit, 1951. Online: http://martinetl.free.fr/suzannebriet/questcequeladocumentation/briet.pdf

On May 23rd 2021, the planet Saturn appears to be stationary among the surrounding celestial bodies in the night sky.1 This is an attempt to capture this planetary standstill.2

A telescope is set up in a pasture, near a forest edge, pointed to the south-southeast morning sky.3

The standstill is de facto inexistent. It’s the moment when Saturn’s apparent prograde motion turns to a retrograde motion. Since Earth completes its orbit in a shorter period of time than the planets outside its orbit, it periodically overtakes them, like a faster car on a multi-lane highway. When this occurs, the planet being passed will first appear to stop its eastward drift, and then drift back toward the west.

In astrology, Saturn’s retrograde movement is generally a time of karmic rebalancing. Previous bad behavior could be punished. But hard work and responsibility could also be rewarded.

This is the third instalment of De Cleene De Cleene’s Public Observatory. Thanks to Volkssterrenwacht Mira, Grimbergen.

Briet, S. Qu’est-ce que la documentation? Paris: Edit, 1951.

Gittelman, L. Paper Knowledge. Toward a Media History of Documents. Durham/London: Duke University Press, 2014.

Oxford English Dictionary Online. Accessed on 13.05.2021.

‘Saturn Retrograde May 23, 2021 – Karmic Love’, Astrology King. Accessed on 15.05.2021.

A half a day’s walk from the Fuente Dé teleférico, there are less and less traces of passers-by. The path to Sotres suddenly runs through a lusher green. The fence between two pastures keeps the sheep from crossing and coincides with the border between two regions. A hole in the fence would change the landscape’s hue.

On the second to last day of a research visit at CERN, there was some spare time in the schedule. I took a long walk towards building 282 in search of some excavation samples: cylindrical pieces of rock that were preserved when the tunnel was dug, glued to a block of wood and frequently exhibited in museums over the last three decades as material evidence of the earthwork and as a witness to the depth. The route led me along the back of building 363 where the wind caused young trees – now gone – to scuff the facade over time.

First published in: De Cleene, M. Reference Guide. Amsterdam: Roma Publications, 2019, as W.569.EXC CERN, Towards Building 282, in search of excavation samples

‘The masons in training pour a concrete slab and build four walls upon it in a stretcher bond. Then the block comes to our department and the students in the course Electrical installer (residential) can grind channels and drill cavities in it.’

[…]

‘It’s not always a success from the outset, but they learn quickly.’

[…]

‘Never grind horizontally, always vertically. Diagonally if there is no other way.’

[…]

‘Two fingers wide.’

[…]

‘After this it goes to the sanitary department. After the bell drilling, the demolition hammer follows and the masons make us a new block.’

Competentiecentrum VDAB, Wondelgem, July 2019.

First published in A+ Architecture in Belgium, A+ 279, Schools (August, September 2019), https://www.a-plus.be/nl/tijdschrift/schools

In his debut novel ‘De Metsiers’ Hugo Claus employs a multiple narrative perspective. In the copy I picked up in a thrift store, there’s a bookmarker between pages 44 and 45 where the perspective shifts from Ana to Jim Braddok. It’s pouring. The pink piece of paper lists 9 sessions at a driving school. There’s a total of 20 hours, taught alternately by Johan and Guy.

In 2000, 2006 and 2017 the twenty-sixth of December was a Tuesday. (Earlier years are improbable, since the Euro was not introduced yet.)

Claus, H. De Metsiers. Amsterdam: Uitgeverij De Bezige Bij, 1978.

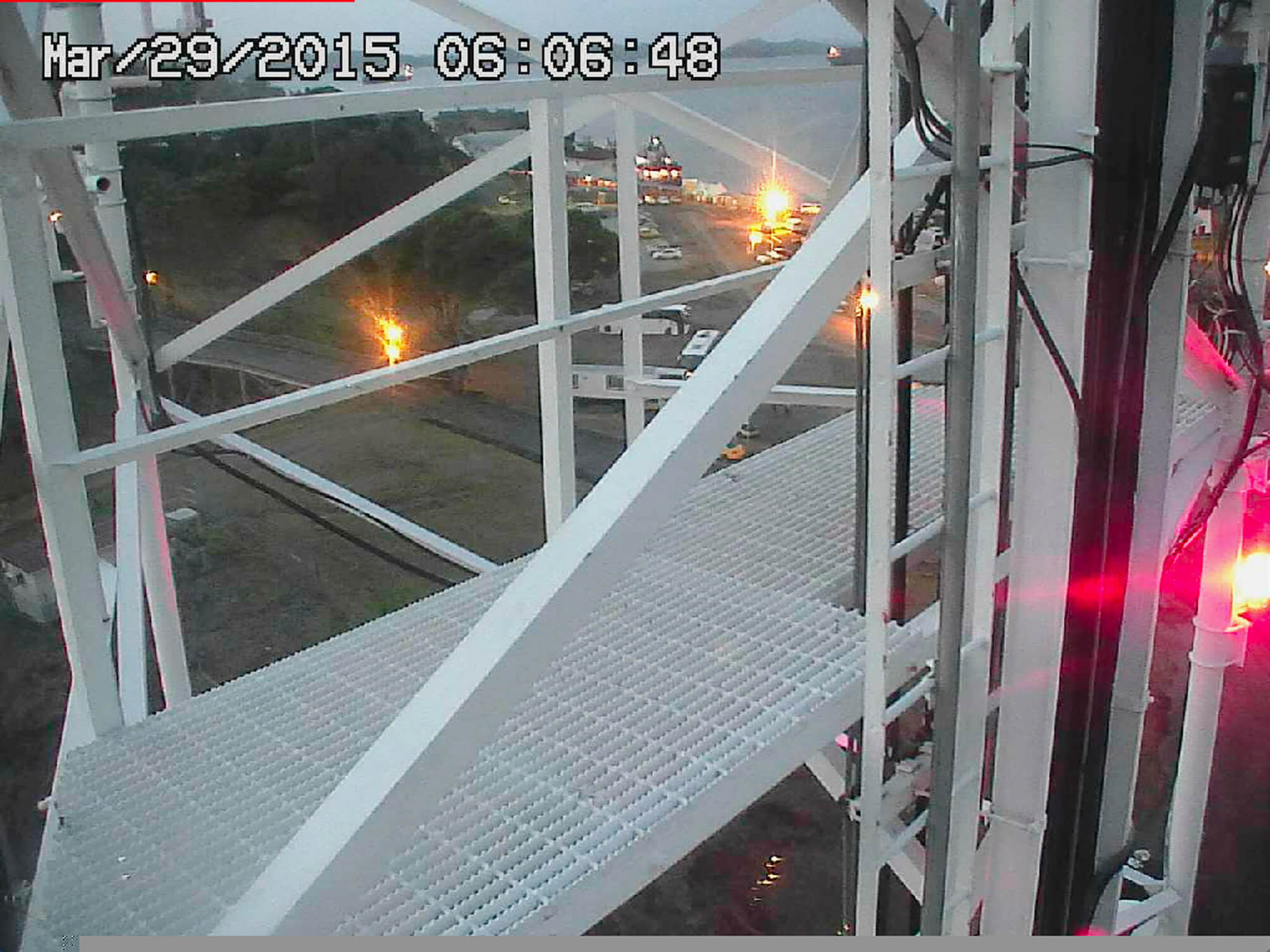

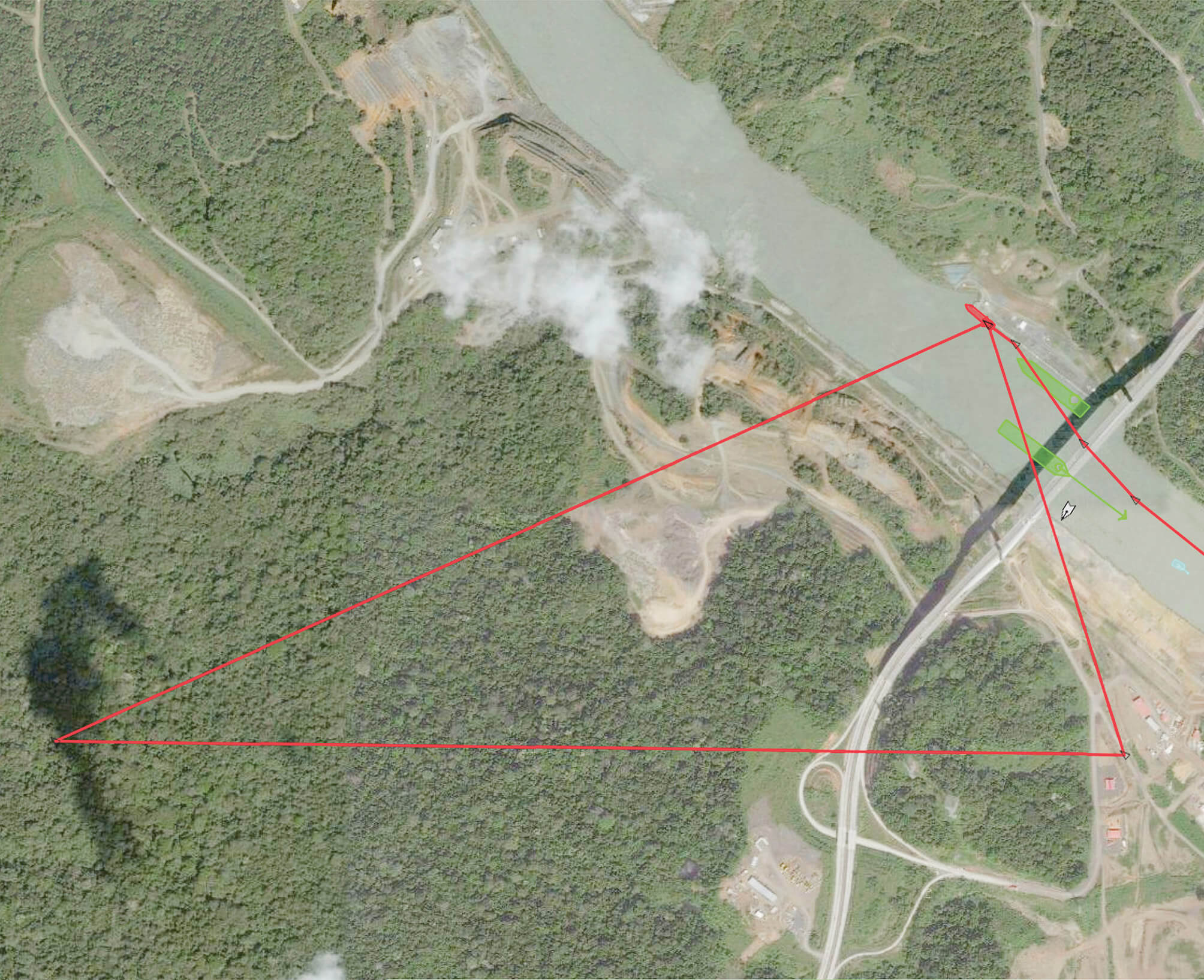

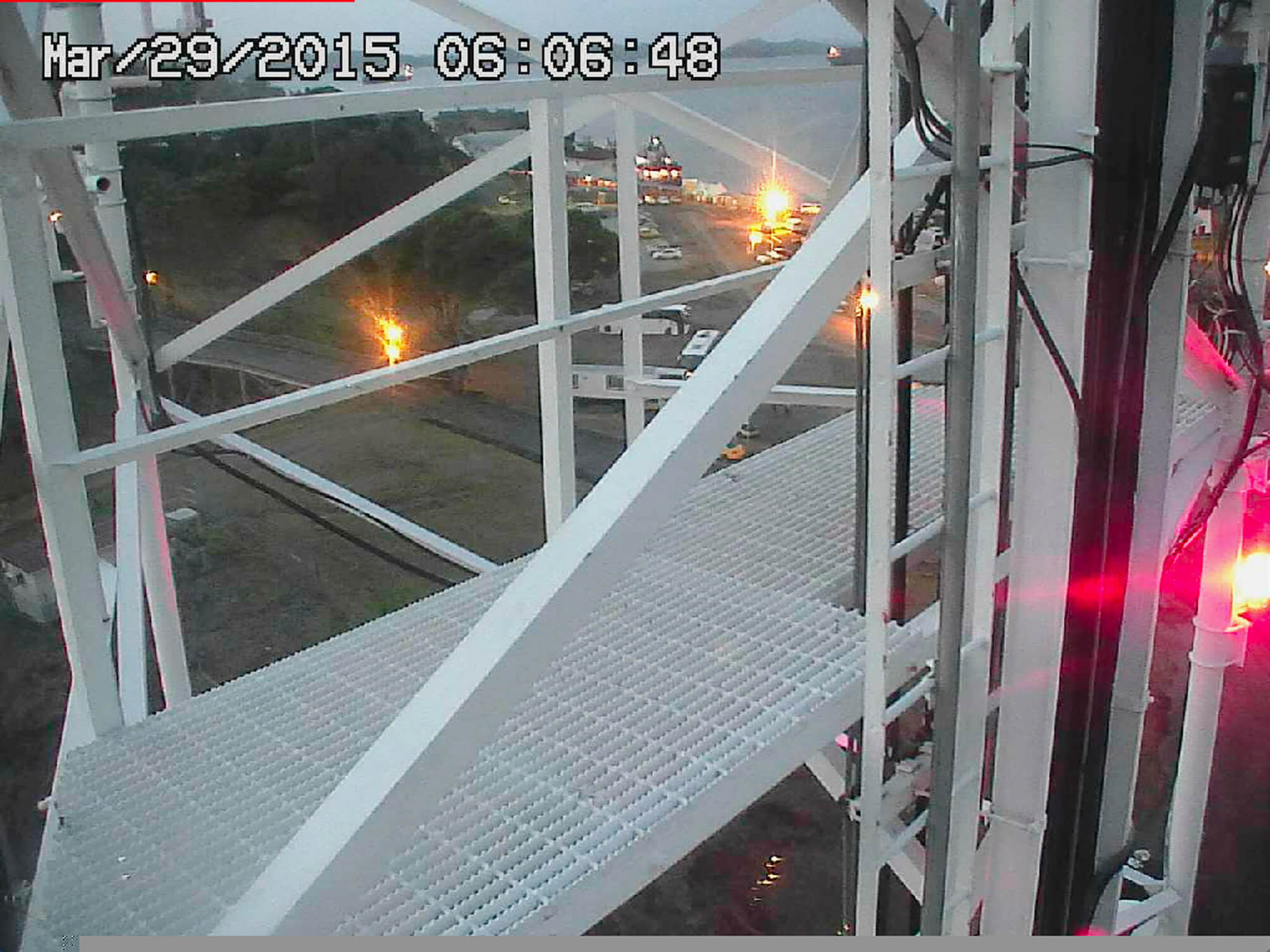

On March 23th 2015, a high pressure system above Panama Bay blew strong winds landwards. At the Gatun locks, one of the webcams overlooking the Canal neglected the traffic and briefly captured its own images. The ship’s presumed passage through the Gatun locks wasn’t recorded by this camera and the AIS-transponder did not save any data of the ship’s transit from the Pacific to the Atlantic side of the canal: the Authenticity managed to swap oceans undetected.

On February 16th 2016, the transponder still signals the ship near the port of Bahia Las Minas. The current is calm, the ship has been practically immobile for a year.

First published in: De Cleene, M. Reference Guide. Amsterdam: Roma Publications, 2019

Webcam Gatun Locks, Panama Canal, http://www.pancanal.com

The Authenticity bunkered crude fuel in the Panama Bay. She navigated back and forth between the artificial island Isla Melones and ships leaving or waiting to enter the Panama Canal. On February 14th 2015 she had been moored for a couple of days near the Centennial bridge when the AIS-transponder momentarily signalled the ship’s position in the woods of the Bosque Protector de Arraiján. Afterwards no signal of the ship was received for 41 days, until she reappeared near the port of Bahia Las Minas, at the other side of the Panama Canal.

First published in: De Cleene, M. Reference Guide. Amsterdam: Roma Publications, 2019

Marine Traffic, Authenticity (Caribe Trader, PA), latest position, 09°01’40,71” N 79°38’18,59”W, viewed 14.02.2015, http://www.marinetraffic.com

On March 23th 2015, a high pressure system above Panama Bay blew strong winds landwards. At the Gatun locks, one of the webcams overlooking the Canal neglected the traffic and briefly captured its own images. The ship’s presumed passage through the Gatun locks wasn’t recorded by this camera and the AIS-transponder did not save any data of the ship’s transit from the Pacific to the Atlantic side of the canal: the Authenticity managed to swap oceans undetected.

On February 16th 2016, the transponder still signals the ship near the port of Bahia Las Minas. The current is calm, the ship has been practically immobile for a year.

First published in: De Cleene, M. Reference Guide. Amsterdam: Roma Publications, 2019

Webcam Gatun Locks, Panama Canal, http://www.pancanal.com

Ten years ago, in November, I drove up to Frisia – the northernmost province of The Netherlands. I was there to document the remains of air watchtowers: a network of 276 towers that were built in the fifties and sixties to warn the troops and population of possible aerial danger coming from the Soviet Union. It was very windy. The camera shook heavily. The poplars surrounding the concrete tower leaned heavily to one side.

I drove up to the seaside, a few kilometers farther. The wind was still strong when I reached the grassy dike that overlooked the kite-filled beach. I exposed the last piece of film left on the roll. Strong gusts of wind blew landwards.

Months later I didn’t bother to blow off the dust that had settled on the film before scanning it. A photograph without use, with low resolution, made for the sake of the archive’s completeness.

The dust on the film appears to be carried landwards, by the same gust of wind lifting the kites.

On March 23th 2015, a high pressure system above Panama Bay blew strong winds landwards. At the Gatun locks, one of the webcams overlooking the Canal neglected the traffic and briefly captured its own images. The ship’s presumed passage through the Gatun locks wasn’t recorded by this camera and the AIS-transponder did not save any data of the ship’s transit from the Pacific to the Atlantic side of the canal: the Authenticity managed to swap oceans undetected.

On February 16th 2016, the transponder still signals the ship near the port of Bahia Las Minas. The current is calm, the ship has been practically immobile for a year.

First published in: De Cleene, M. Reference Guide. Amsterdam: Roma Publications, 2019

Webcam Gatun Locks, Panama Canal, http://www.pancanal.com

In between two cities along the Belgian coast, water has run from the dunes (and the Second World War Heritage site scattered among them), underneath the coastal road and tram rails, to the beach. It has formed a small S-shaped estuary, bound to disappear due to the increasingly harsh wind coming from the coast of Britain, blowing North-easterly, and hammering down on the levee. The vibrations of the empty Ostend-bound tram passing just before the photograph was taken, had no visible impact on the estuary.

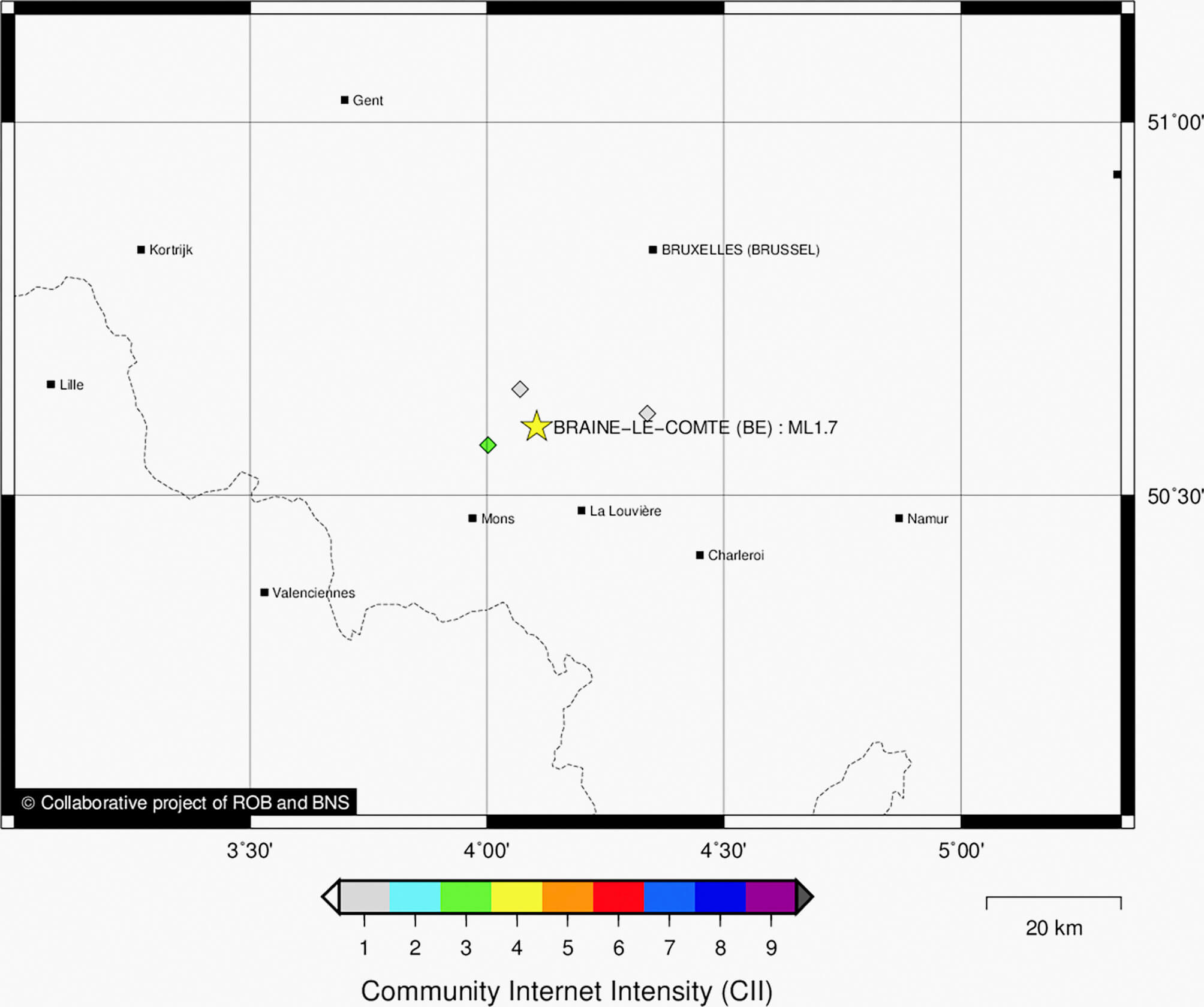

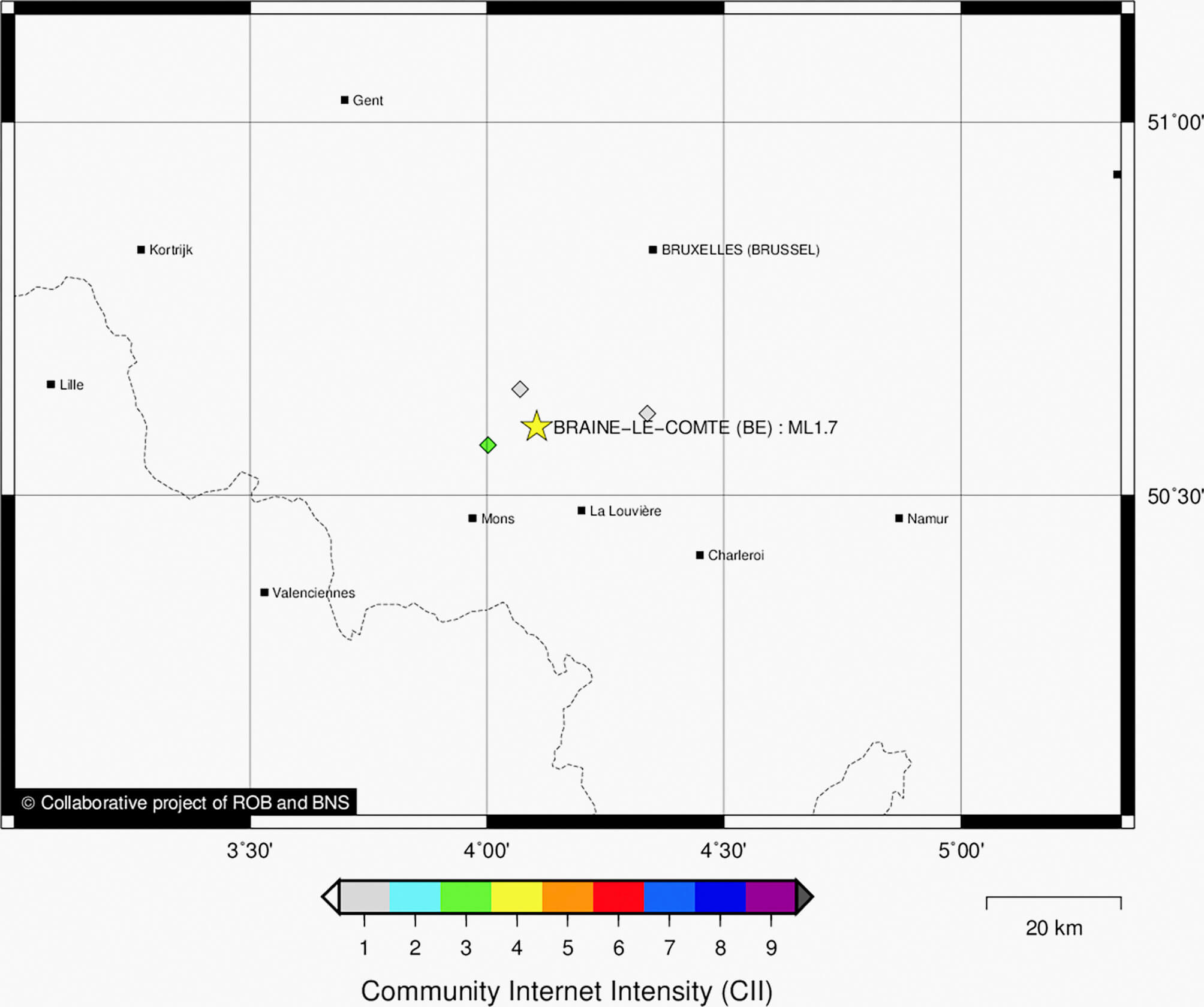

On May 6th 2020, 14h06 and 31 seconds, the Belgian Seismological Institute records an earthquake with a 1,7 magnitude in the region of Braine-Le-Compte. Three reactions from people in the neighbourhood, filed by the Institute, confirm the official seismological recordings. The Institute’s website classifies the earthquake as a ‘quarry blast’.

http://seismologie.be/nl/seismologie/aardbevingen-in-belgie/en130qj1o

The road down from the top of Mount Vesuvius, at Atrio Del Cavallo. The sun sets. The last tourist bus has headed down. Then the headlights of the guardian’s car swing their way down. It must be freezing. I am holding an orange-sized piece of petrified lava, probably stemming from the 1872 or 1944 eruption. A kilometer further down the road, the old Observatory is empty. Nowadays, monitoring seismic changes is done in a research centre in the city of Naples. Their seismographic registrations can be followed online, in real time. Two headlights swirling along the slopes, underneath me, are coming upwards.

During the night, both of us get unwell. One of us is shaking, intensely and relentlessly. The windows are open. For minutes that seem to be hours, it feels like it’s freezing. We get extra blankets. Then, it gets too hot.

One of us dreams about coccodrillos. It starts out with a single animal, like the one we saw in the National Archaeological Museum, escaping from an aquarium, and ends with lots of little ones crawling all over the place. It’s impossible to know how many have escaped.

The other dreams about seismologist Luigi Palmieri’s unfortunate assistant and his family’s quest to redeem his good name. To deprive him of the burden and guilt set upon him by Luigi Palmieri’s report of the 1872 eruption of Vesuvius, the assistant’s offspring were building a monument just below the observatory in which their great-grandfather fell asleep. The monument was permanently, and continuously, unfinished.

We both dream of hearing fireworks in Naples.

In the morning, we’re slightly alarmed that we both got sick and feverish at the same instant. It’s the middle of January, and the weather has been summerlike all week. A gentle morning breeze flies in from the Neapolitan bay while we wait for the bus to take us to the airport.

First published as part of De Cleene De Cleene. ‘Amidst the Fire, I Was Not Burnt’, Trigger (Special issue: Uncertainty), 2. FOMU/Fw:Books, 25-30

Our one year old’s favourite toy he’s not supposed to play with is the HP Officejet Pro L7590 All-in-one in my office. I have given up on forbidding him to play with it. We have a new game: he brings me one of his other toys, we put it on the flatbed, close the lid – as far as possible –, press the button ‘START COPY – COLOR’ and wait for the print to come out of the machine. When we place the original onto the copy, he laughs. So far we have copied his blue pacifier, his planet-earth-bouncy-ball and his rattling crocodile.

During the night, both of us get unwell. One of us is shaking, intensely and relentlessly. The windows are open. For minutes that seem to be hours, it feels like it’s freezing. We get extra blankets. Then, it gets too hot.

One of us dreams about coccodrillos. It starts out with a single animal, like the one we saw in the National Archaeological Museum, escaping from an aquarium, and ends with lots of little ones crawling all over the place. It’s impossible to know how many have escaped.

The other dreams about seismologist Luigi Palmieri’s unfortunate assistant and his family’s quest to redeem his good name. To deprive him of the burden and guilt set upon him by Luigi Palmieri’s report of the 1872 eruption of Vesuvius, the assistant’s offspring were building a monument just below the observatory in which their great-grandfather fell asleep. The monument was permanently, and continuously, unfinished.

We both dream of hearing fireworks in Naples.

In the morning, we’re slightly alarmed that we both got sick and feverish at the same instant. It’s the middle of January, and the weather has been summerlike all week. A gentle morning breeze flies in from the Neapolitan bay while we wait for the bus to take us to the airport.

First published as part of De Cleene De Cleene. ‘Amidst the Fire, I Was Not Burnt’, Trigger (Special issue: Uncertainty), 2. FOMU/Fw:Books, 25-30

In Boarhunt, close to Winchester (UK), the fort houses the Royal Armouries’ artillery collection. It contains parts of the ‘Project Babylon’ space gun, the two part bronze Dardanelles Gun and a collection of French field guns, captured in Waterloo. On the lawn to the South of the fort two neat piles of fifteen1 36” shells flank a Mallet’s Mortar. Manufactured in 1857, the mortar remains unfired up to this day.2 In 1873, its inventor – the engineer and geophysicist Robert Mallet – publishes his translation of Luigi Palmieri’s Incendio Vesuviano. Before giving a lengthy account of his take on the present state of vulcanicity, he briefly introduces the famous Italian vulcanologist’s report: ‘The following Memoir of Signor Palmieri on the eruption of Vesuvius in April of this year (1872), brief as it is, embraces two distinct subjects, viz., his narrative as an eye-witness of the actual events of the eruption as they occurred upon the cone and slopes of the mountain, and his observations as to pulses emanating from its interior, as indicated by his Seismograph, and as to the electric conditions of the overhanging cloud of smoke (so called) and ashes, as indicated by his bifilar electrometer, both established at the Observatory.’

O

O OOO

OOO OOOOOOO

In the outskirts of East of London, along Repository road in Woolwich, the only other mortar of this type is installed. This particular one fired nineteen shells on three occasions. Each time resulting in a damaged mortar.

Screenshot taken from AbeBooks, where the first edition of The Eruption of Vesuvius in 1872 with Notes, and an Introductory Sketch on the Present State of Knowledge of Terrestrial Vulcanicity, the Cosmical Nature and Relations of Volcanoes and Earthquakes is listed for 1895,00 USD. https://www.abebooks.com/first-edition/Eruption-Vesuvius-1872.with-Notes-Introductory-Sketch/439314424/bd

Project Gutenberg’s The Eruption of Vesuvius in 1872, by Luigi Palmieri (translated by Mallet) can be found at: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/33483/33483-h/33483-h.htm

The road down from the top of Mount Vesuvius, at Atrio Del Cavallo. The sun sets. The last tourist bus has headed down. Then the headlights of the guardian’s car swing their way down. It must be freezing. I am holding an orange-sized piece of petrified lava, probably stemming from the 1872 or 1944 eruption. A kilometer further down the road, the old Observatory is empty. Nowadays, monitoring seismic changes is done in a research centre in the city of Naples. Their seismographic registrations can be followed online, in real time. Two headlights swirling along the slopes, underneath me, are coming upwards.

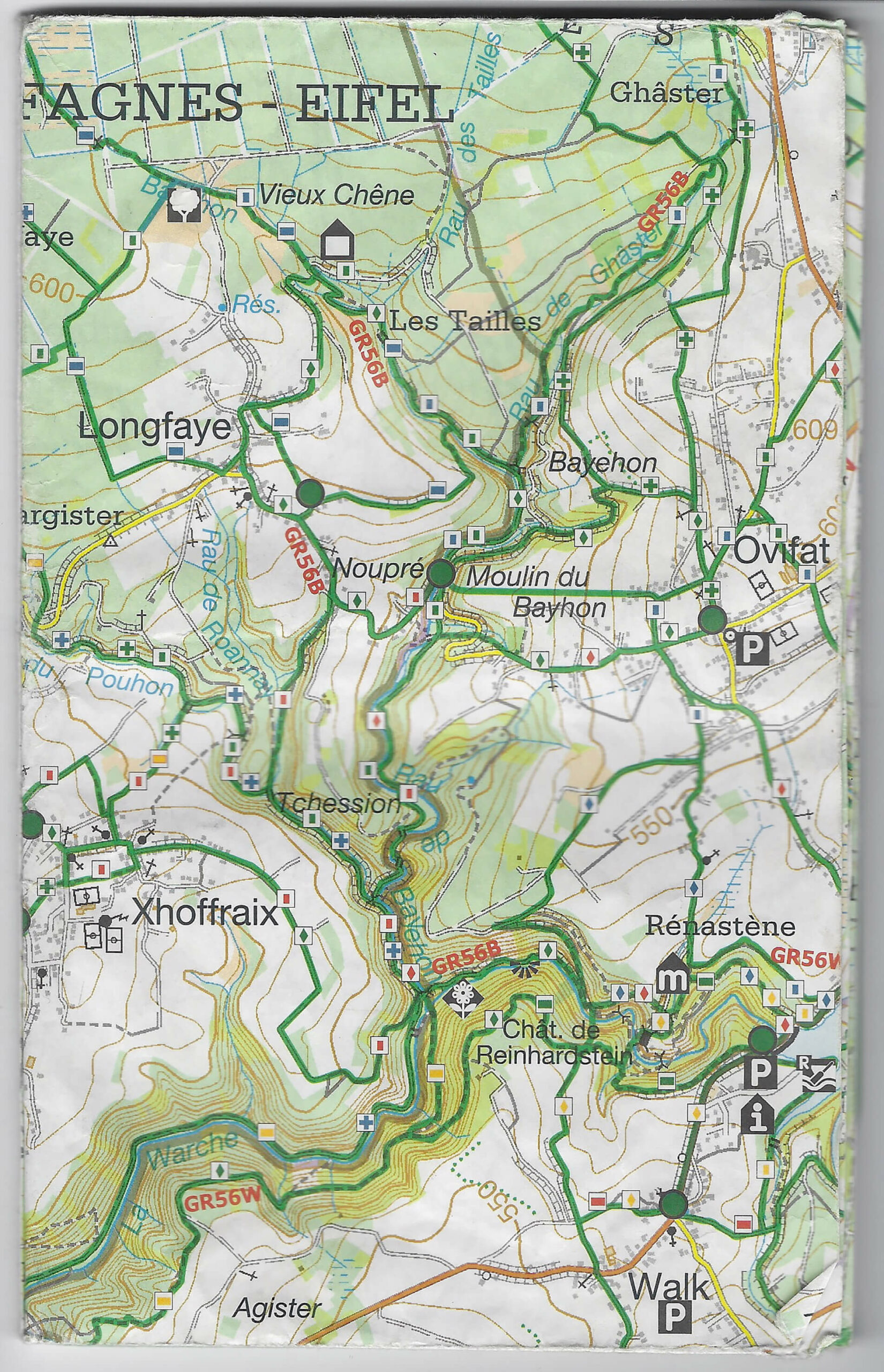

The paths in the valley of the Bayehon are covered with ice. We are making our way down towards the valley of the Ghâster. The temperature is minus 15 degrees Celsius. The water in our drinking bottles is frozen. We are betting on the shelter indicated on the map (Au Pied des Fagnes, Carte De Promenades, 1:25.000, Institut Geographique National) to pitch our tent. There is almost no wind, but every breath of air feels like we’re being hit with a thousand needles. What the map indicates as a shelter appears to be a picnic table.

Fairly detailed map of the two major marble quarries on the island of Tinos, Greece. The spontaneous route-advice was prepared by a local marble worker, P.D., in the Karia region of the island on a locally extracted, green marble slab. The waved lines represent roads traversing uphill, while the straight lines represent roads following a contour line of the topography.

‘Tell your friend that the wine is for girls; it’s very sweet,’ the marble worker alerted my travel companion K.S. after offering us local sweet wine. The workshop smelled like boiled meat and bones.

Notes on map from left to right, top to bottom:

- Towards Vathi

- Quarry

- incomprehensible

- Towards Vathi Bleu

- Isternia

- Pirgos

Márk Redele pursues projects that fundamentally relate to architecture and its practice but rarely look like architecture. www.markredele.com

On May 6th 2020, 14h06 and 31 seconds, the Belgian Seismological Institute records an earthquake with a 1,7 magnitude in the region of Braine-Le-Compte. Three reactions from people in the neighbourhood, filed by the Institute, confirm the official seismological recordings. The Institute’s website classifies the earthquake as a ‘quarry blast’.

http://seismologie.be/nl/seismologie/aardbevingen-in-belgie/en130qj1o

The road down from the top of Mount Vesuvius, at Atrio Del Cavallo. The sun sets. The last tourist bus has headed down. Then the headlights of the guardian’s car swing their way down. It must be freezing. I am holding an orange-sized piece of petrified lava, probably stemming from the 1872 or 1944 eruption. A kilometer further down the road, the old Observatory is empty. Nowadays, monitoring seismic changes is done in a research centre in the city of Naples. Their seismographic registrations can be followed online, in real time. Two headlights swirling along the slopes, underneath me, are coming upwards.

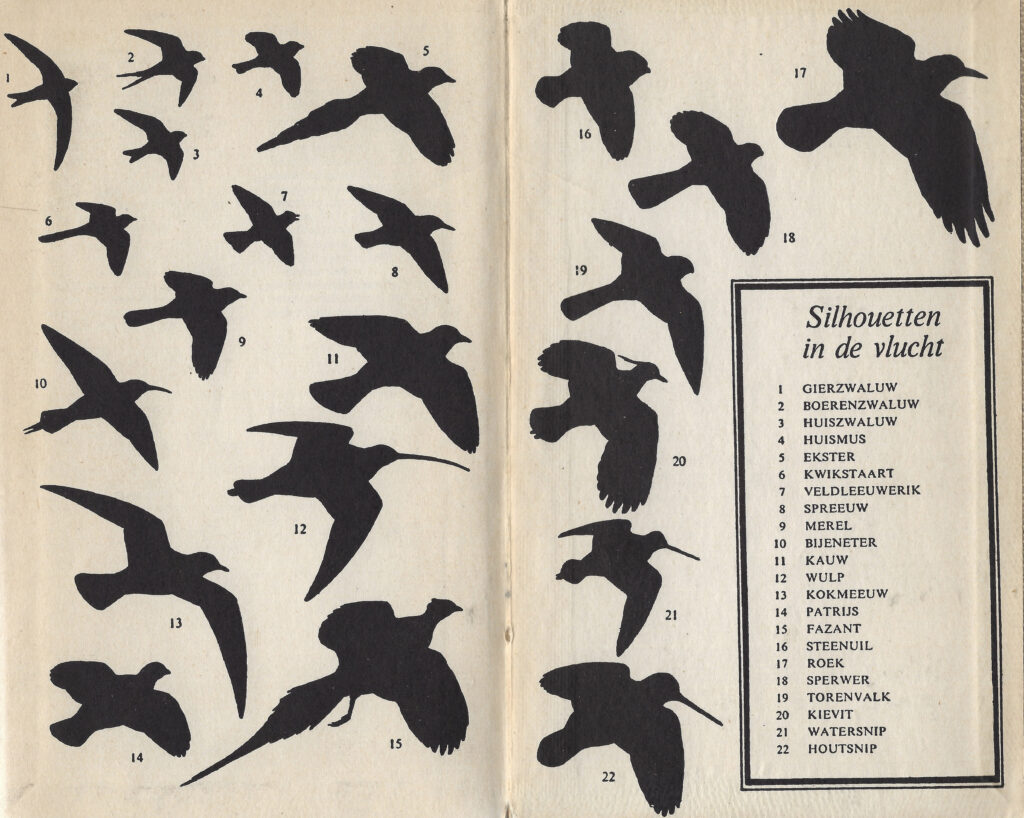

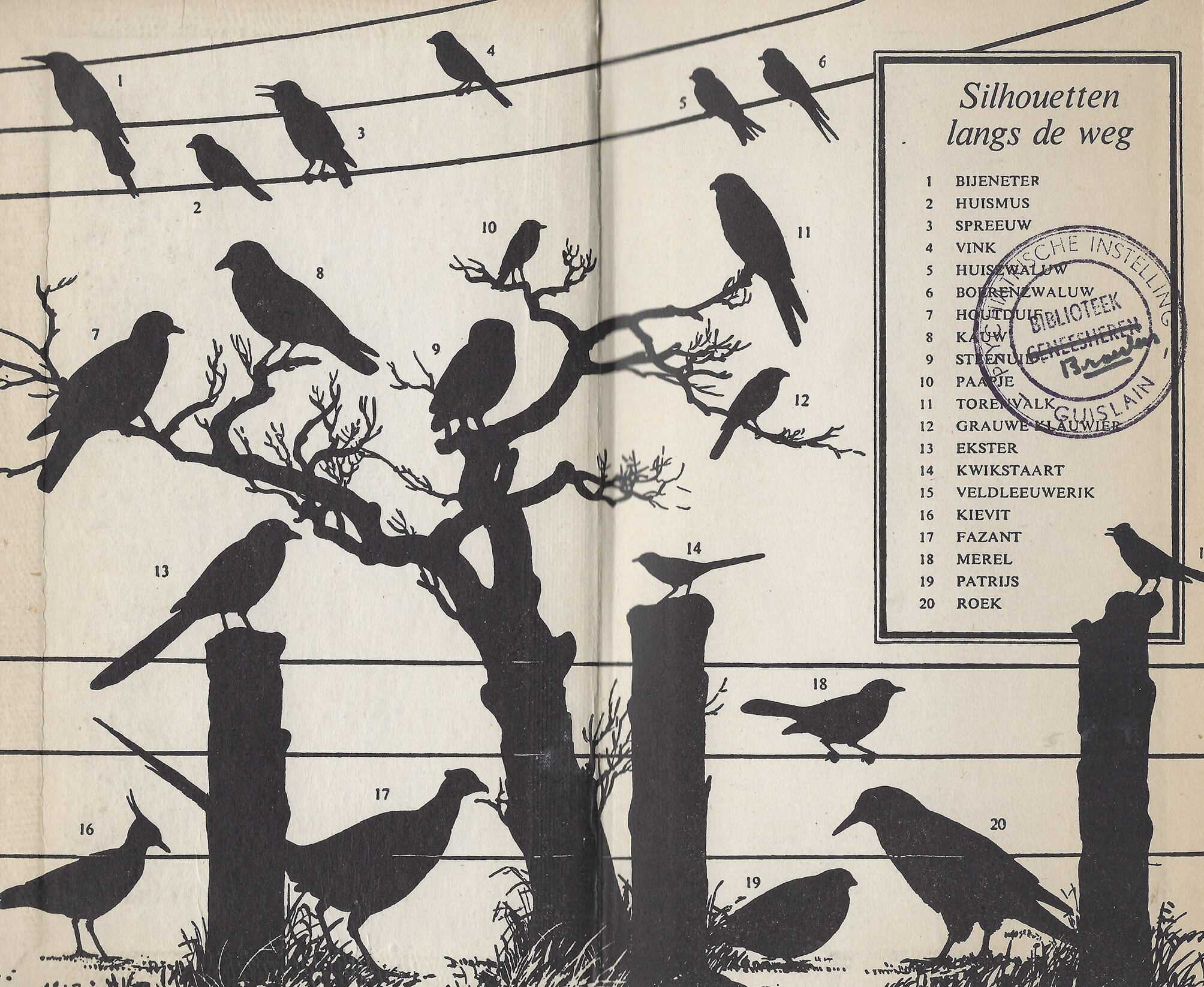

This is the spread one sees upon opening the bird field guide that once stood, as the stamp indicates, in the library of a psychiatric institution.1 It shows birds’ silhouettes, as they can be seen beside the road.

The drawing has a kind of Hitchcock feel to it.2 The birds seem to be spying on each other, as they also seem to be spying on the unsuspecting passer-by.

The composition of the scene is marvelous. The electric wires, the tree, the wire fence, the double framed list with the birds’ names, handsomely positioned in a birdless patch, at once superimposed on the telephone wires, and pushed to the background by the skylark.

Imagine seeing this scene. What are the odds: to see the silhouettes of Europe’s twenty most common species of birds in one glance, from your car’s window, as you are driving home at dusk.

Before closing the book, the last spread seems to show the birds fleeing, maybe attacking.3

The stamp indicates that, at the psychiatric institution, the book was part of the sublibrary for the Catholic Brothers of Charity. The crossed-out part indicates that there was also a separate physicians’ library, to which the book might have originally belonged.

On the web, discussions on whether Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds (1963) was shot in colour or in black and white, abound.

Peterson, R.T., Mountfort, G. & P.A.D. Hollom. Vogelgids voor alle in ons land en overig Europa voorkomende vogelsoorten (J. Kist, transl.). 3d ed. Amsterdam/Brussels: Elsevier, 1955.

Belgium, approximately 1.5km from the French border, photograph made on 16.06.2018.

The European flag symbolises both the European Union and, more broadly, the identity and unity of Europe. It features a circle of 12 gold stars on a blue background. They stand for the ideals of unity, solidarity and harmony among the peoples of Europe. The number of stars has nothing to do with the number of member countries, though the circle is a symbol of unity.1

- Coat of arms of Gmina Puck, a rural district in Puck County, Pomeranian Voivodeship, in northern Poland.

- Illegible.

- F.C. Hansa, Mecklenburg, Pommern, FC Hansa Rostock is a German association football club based in the city of Rostock, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern. They have emerged as one of the most successful clubs from the former East Germany and have made several appearances in the top-flight Bundesliga. Hansa Rostock’s official anthem is “FC Hansa, wir lieben Dich total”. Hansa struggles with hooliganism, estimating up to 500 supporters to be leaning towards violence. The club’s logo consists of a red sailing ship with a blue sail showing the Rostock Griffin.

- Mon École Écologique.org is an organization for environmental conservation. On 07.01.2021 there was no website listed on this URL.

- Illegible.

- Illegible, apart from ’1962’ in the middle.

- Innocenti Bruderschaft, EL, 2018, a community of German Lambretta Innocenti riders and aficionados.

- Imag’Ink, Bretignolles Sur Mer, Tatoueur, 06 06 44 13 51, a French tattoo shop.

- Illegible.

- Hardly legible, the only word that can be made out is ‘Futbolom’: Russian for soccer.

- Kaluga on tour. Kaluga is a Russian city 150km southwest of Moscow. It is often called the cradle of space exploration thanks to the city’s most famous resident: Konstantin Tsiolkovsky.

- Hansa Ultras, F.C. Hansa. The Ultras are a group of F.C. Hansa fans (see: ‘3’).

- Illegible because ‘12’ was stuck over it.

- Illegible.

- La Hutoise is a regional student-association for higher education students from the Belgian town of Huy and its surroundings. Its aim is to bring together students from Huy in a spirit of camaraderie and to perpetuate student folklore. The logo consists of a two headed bird of prey with a cap on each head. The bird wears a scarf over one shoulder and holds a glass of beer in each paw.

- F.C. Hansa, Grimmen. The F.C. Hansa logo (see ‘3’ and ‘12’) is combined with the coat of arms of Grimmen: a griffin on a pile of 10 bricks. Grimmen is a German town in Nordvorpommern on the banks of the river Trebel.

- Illegible.

- Heil Hansa. To the left of this text the F.C. Hansa logo (see ‘3’, ‘12’ and ‘16’), on the right a logo consisting of a black bull with his tongue out and a golden crown on his head. This controversial sticker lead to several arrests in the run-up to the match between F.C. Hansa Rostock and Bayern München in February 2020. Supporters of F.C. Hansa had attached this sticker to public buildings on their way to the stadium.

- Illegible because ‘16’ was stuck over it.

- The Cuban flag.

- Illegible.

- Illegible.

- Kaluga (see ‘11’).

- De Veterinnen, a round, black sticker with a red print of a head wearing a round hat and a carnivalesque collar with a carrot for a nose. No further information found.

- Zlombol 11. Złombol is a yearly charity car rally racing event that starts in Katowice Poland. Contesters must drive a car that was built or designed during the communist era. The destination of the 2011 edition was Loch Ness.

- F.C. Hansa, Mecklenburg, Pommern, identical sticker to ‘3’, see also ‘12’, ‘16’, and ‘18’.

- Torpedo Moscow, only for white. Football club Torpedo Moscow is a Russian professional club based in Moscow, founded in 1930. Some fans of the club wave far-right symbols and banners, both during and outside of matches. Massive fan-protest ensued when the club tried to sign a black player in 2018. The player’s contract was cancelled.

- Heil Hansa. See ‘3’, ‘12’, ‘16’, ‘18’ and ‘26’.

- Illegible.

- Illegible.

- Illegible.

- Illegible.

- F.C. Hansa. Variation of ‘3’ and ‘26’ with a circle of yellow crops around the logo. See also ‘12’, ‘16’, ‘18’ and ‘28’.

- Live animals, contents: Rivne UA. These stickers are required by the International Air Transport Association for airline cargo pet travel. Rivne is a city in western Ukraine (UA) with an international airport. The sticker does not specify the transported animal but displays a dog, two birds, two fish and a turtle.

- Illegible.

- Illegible.

- Illegible.

- Illegible, apart from ‘lska’ on the bottom.

- Norrland Fly Guys, Reading Water. The sticker displays a minimal landscape with two pine trees, and a shed on a chunk of floating ice, a single four-point star shines in the sky. Norrland is the northernmost part of Sweden. No further information found. Whether the ‘fly guys’ own airplanes or are involved in fly fishing is unclear.

- This sticker displays – what appears to be – a smiling potato in front of an enlarged snow crystal. No further information found.

- Traumsucht is an artist collective from Berlin. Their website lists German rap-artists

- Illegible.

https://europa.eu/european-union/about-eu/symbols/flag_en

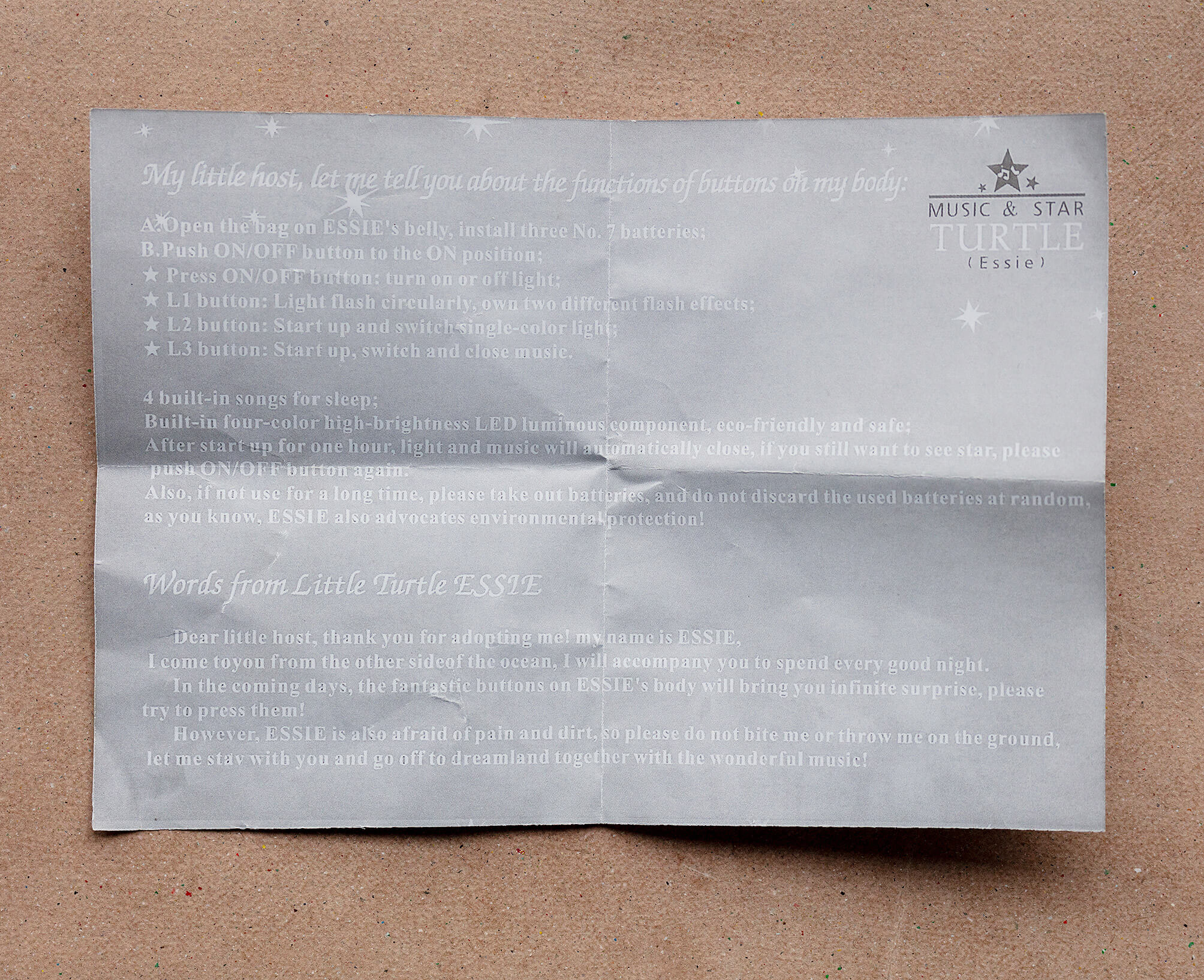

I bought my son a gift while abroad: a toy turtle named Essie whose perforated shield projects stars onto the ceiling in blue, green or amber. ‘8 actual star constellations’, the box proclaims.

The manual explains how to power up the turtle and what the four buttons on Essie’s back do. The small document (recto: Chinese, verso: English) concludes with some ‘Words from Little Turtle ESSIE’. In it the turtle shifts from direct speech to illeism1 and back.

The act of referring to oneself in the third instead of first person.

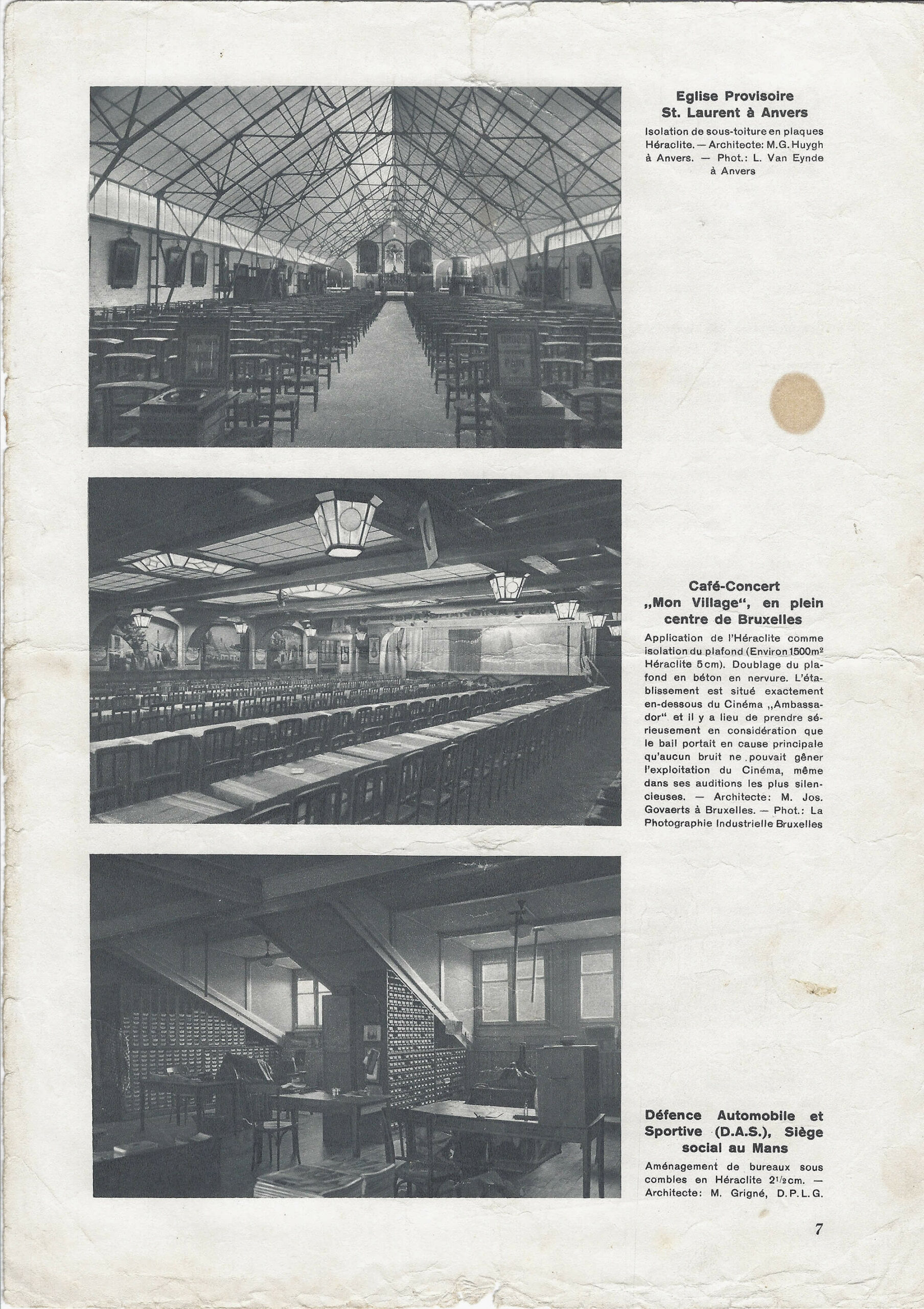

All chairs are empty, but all face something different. The bottom photograph shows empty chairs facing empty desks. In the middle picture, empty chairs face each other (underneath the inaudible sound of the cinema above). In the top photograph, the chairs seem to be facing the photographer. However, the altar’s in front of the photographer. He stands at the back of the provisional church. The chairs face the photographer and have turned their backs to the altar.

Revue Héraclite, 5 (1), april 1936, p. 7, paper, from the archive of architect O. Clemminck.

At the State Archive in Kortrijk, I am leafing through a 1955 photo album of the construction of the provisional church in Lokeren by the famous furniture company Kunstwerkstede De Coene. Gigantic wooden, prefabricated beams structure the building. It is cold. An old man in a grey suit shuffles between the racks to look up the date of birth of his great great grandmother. Snow covers the unfinished provisional roof. A bus passes, I reckon, through the pouring rain.

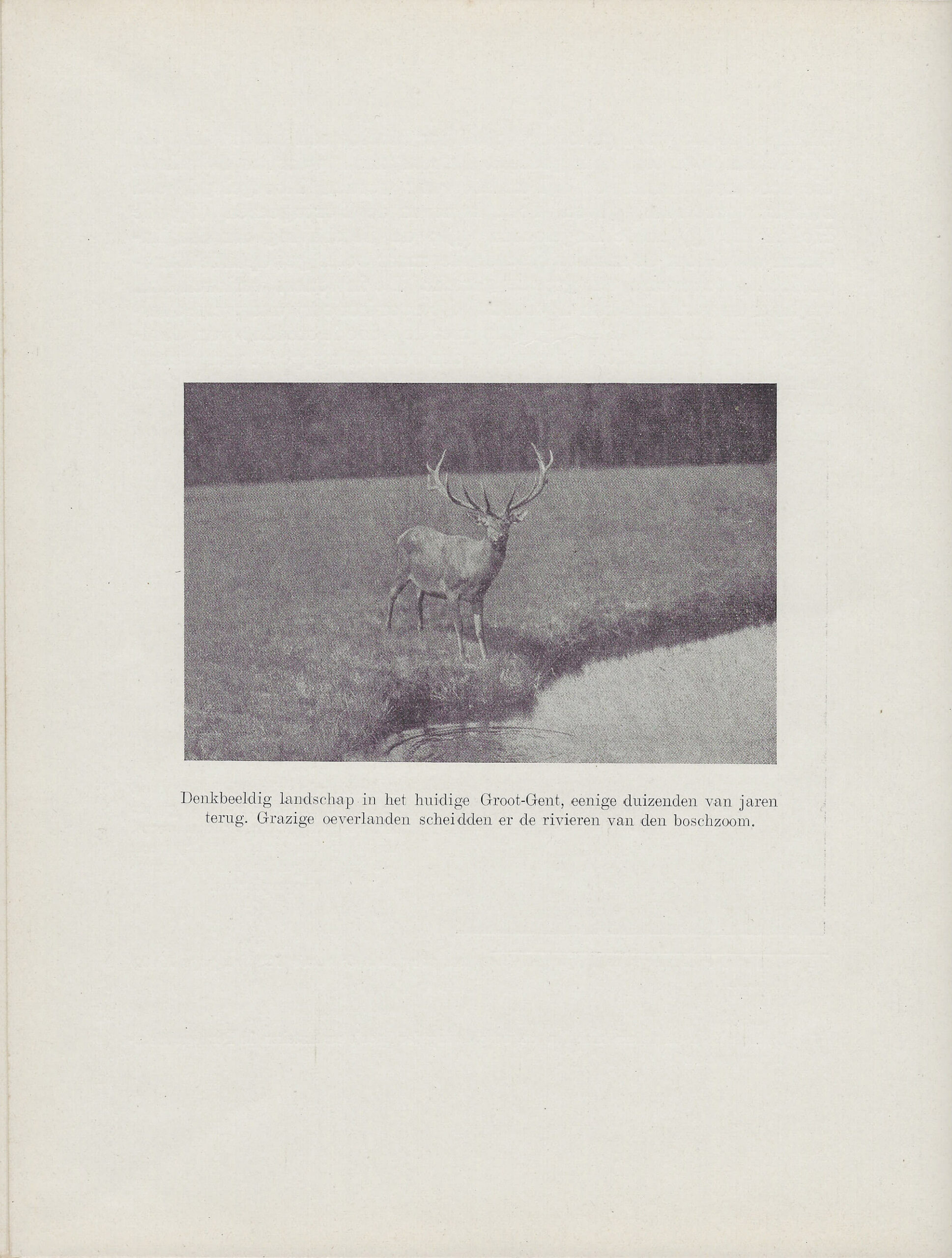

(‘Imaginary landscape in the actual greater Gent, some thousands of years ago. A grassy riparian zone separates rivers from the edge of the forests’)

Imagine a deserted city of Gent, overtaken by nature, Thiery asks the reader in his book Het woud (The Forest). After fifty years, you return to the city. Buildings have collapsed, streets are overgrown. It has become an impenetrable, dense forest, except for the river on which the reader makes his or her way through it. In the first half of the twentieth century, Leo Michel Thiery made one of Belgium’s first botanical gardens for educational purposes. In the middle of an industrialized quarter of the city of Gent, the garden presented different sceneries. There were landscapes from the Alps, dunes, the Ardennes, steppe. Besides sceneries with chalk-, loam-, marl- and sand-based vegetation, there were forests, grasslands and swamps.

After his death, Thiery’s garden decayed. Decades later, it was restored, with the Alps, dunes, the Ardennes and steppe now classified as a protected view.

Thiery, M. Het woud. Een proeve van plantenaardrijkskunde. Gent: De Garve, s.d., p. 14

(‘Slice of more than three meters in diameter, sawn from a Mammoth-tree, given by California to the botanical garden of New York, and presented there’)

Thiery describes the ‘patriarchs’ of the plant world. This slice of a Sequoia, which fell in 1917 in Yosemite National Park, is 1694 years old. A woman of the New York Botanical Institue, where the slice of the patriarch is presented, counted the rings. If one would look at the picture with a magnifying glass, Thiery writes in a footnote, the reader (with good eyes and a fair amount of knowledge of the English language) would be able to read the labels indicating the important global events the tree witnessed. They are transcribed and translated by the author. The end of the Roman occupation of Great Britain. Columbus arriving in America. The Declaration of Independence. This is a lie: the text is illegible, even when using a magnifier.

In the photograph, the slice, as on view in the New York Botanical Institute, is presented upright. To prevent it from rolling away, two small triangular slices of wood were posited at the left and right side of the slice. The type of wood of these slices, nor the age of the patriarch from which they stem, are known.

Thiery, M. Het woud. Een proeve van plantenaardrijkskunde. Gent: De Garve, s.d., p. 59.

Between the rhinos and the kangaroos in the Antwerp Zoo a wooden footpath curves through a grove of Sequoiadendron Giganteum trees. In the middle of this Californian forest, visitors find the giant slice of a felled tree of the same species. It was brought to the zoo in 1962 and was approximately 650 years old at the time. Eleven labels point out significant moments in history on the tree’s growth rings. They range from zoo- and zoology-related moments (for instance: ‘1901: The Okapi is described as a species’, or ‘1843: Foundation of the RZSA and opening of the Zoo’, or ‘1859: Darwin publishes The Origin of Species’, etc.), to cultural and historical milestones (‘1555: Plantijn starts publishing books in Antwerp’, or ‘1640: Rubens (baroque painter) dies’, or ‘1492: Columbus in America’). Another label points to the last growth ring and reads: ‘1962: this tree is felled and this tree disc is installed at the Zoo.’

The label pointing to the centre of the tree implies a simultaneity between the tree’s first growth year and the Battle of the Golden Spurs in 1302.

On closer inspection the slice seems to consist of two halves that were put together like a jigsaw puzzle. The resulting gap is skilfully patched with what appears to be wood from the same species – possibly even the same mammoth tree.

Every two weeks, The New York Review of Books falls into my letterbox. Those are good days. Most often, I won’t get to reading it, but what I instantly do, is check the last page with ‘The Classifieds’. The people writing the (genuine, not fictitious) adverts and inquiries reappear every so often. I happily assume the position of the implied reader, as they address the presumed readers of the review. There’s a ‘charismatic, aging French rock star’ providing original songs in Franglais. There are top notch apartments in Paris for aspiring writers. There are those seeking love and astronomical peculiarities: ‘Hitch my wagon to a star – Looking for a bright sophisticated senior star gazer! CStein3981@aol.com’.

The New York Review of Books, March 11, 2021, Volume LXVIII, Number 4.

Near Avenue 61 on an artificial island close to Seef, a truck is being towed after the driver lost control over the vehicle and flipped it onto its side. A warm wind blows in from the Persian Gulf.

A police officer signals us to come closer. ‘Why are you taking pictures?’ he asks. ‘This is just an accident. You have to delete the pictures from your phone. Now.’ After checking the pictures-folder on our phones, he gets in his car, drives a few metres, stops the car and rolls down his window. ‘And don’t do it again!’ he yells. Then he drives off, raising a cloud of sand in his wake.

Photograph taken and recovered from my trash bin on 18.12.2020.

In June, 2014, a severe hailstorm hit Belgium. Warnings were broadcast. A football game between the national teams of Belgium and Tunisia was paused. The morning after, there were small dents in the hood and the roof of the car, each a square centimeter in size, some 10 centimeters separated from each other. The storm didn’t get a name.

Assessing the damage, the insurance company’s expert took the dents into account to establish the wreck’s worth.

A year ago, mid-August, just before sunrise, the mostly unlit office buildings line the road that leads to the underground parking. I turn off the ignition. I’m in F36. The walls are painted pink. Looking for the exit, I take the escalator and get stuck in an empty shopping mall. The music is playing but all the shops are closed off with steel shutters. So are the exits. I’m out of place. In keeping early customers out, the mall is keeping haphazard visitors in. I’m back in the parking lot. The elevator is broken. I take the stairs and walk by a homeless man, sleeping. There’s shit on the floor. I open the door that leads out of the stairwell. It slams shut behind me. There’s no doorknob. I find myself on a dark floor between mall and parking lot. People are sleeping; some are awake. Heads turn toward me. I start walking slightly uphill towards where I think I might find an exit, or an entrance. The scale of the architecture has shifted from car (F36) and customer (the closed mall) to truck. I find myself amidst the supply-chain. It takes five minutes, maybe fifteen, maybe more to get out and see the office buildings towering over me in the first light of day.

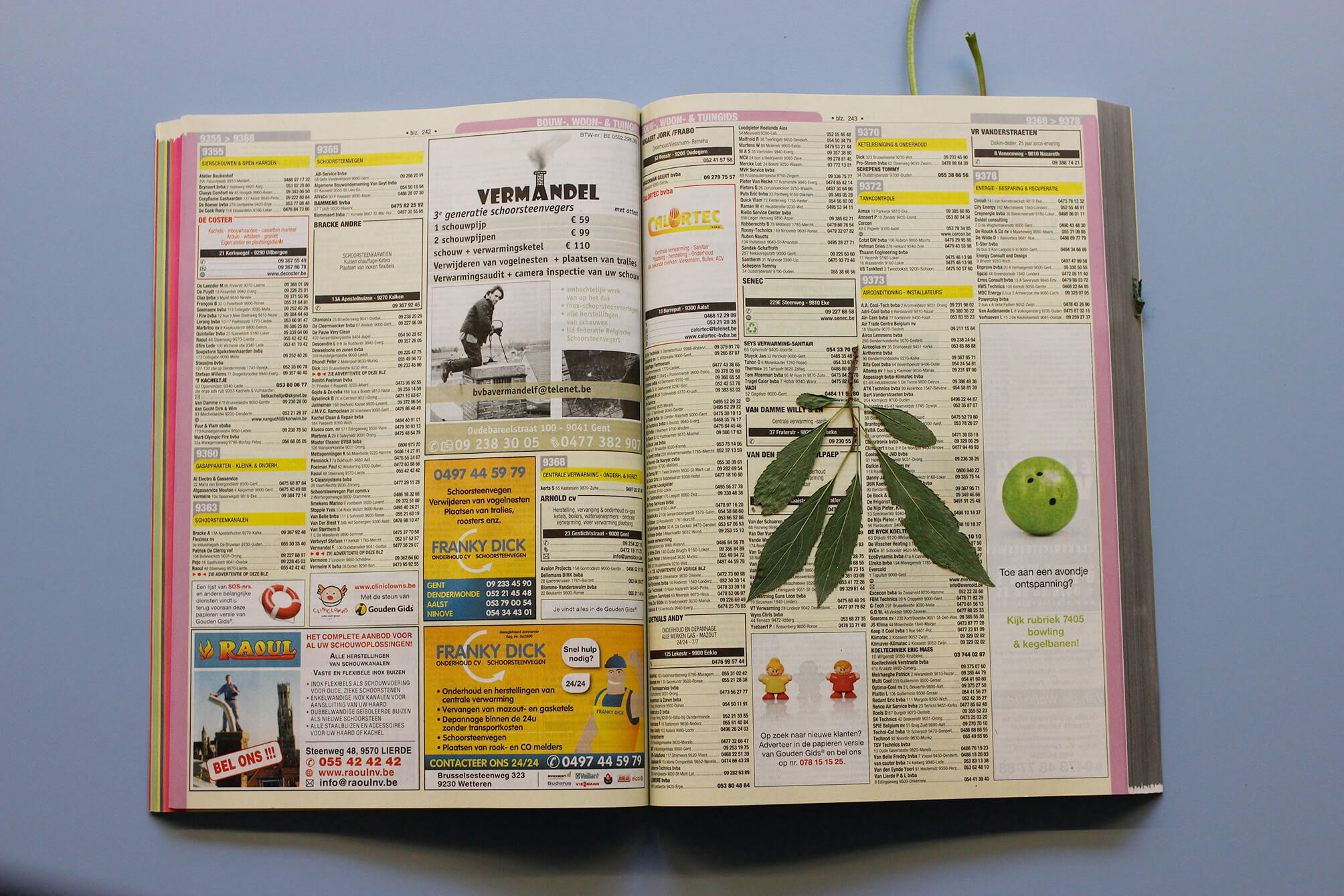

In 2020, the print versions of the Flemish telephone books ‘Gouden Gids’ and ‘Witte Gids’ (The Golden Guide and The White Guide), were published for the last time. From that year onwards, the directory could only be accessed and consulted online. The effect of the production of print telephone directories on the environment is considered to be enormous. As yearly updated, ubiquitous books, they were publications that soon turned superfluous. They led to piles of waste.

From the beginning of the 21st century on, both the print version and the online version had been available. This was a period of medium transition. During the last two decades, the print directory increasingly referred to the websites of the companies listed. To search for e.g. someone to inspect the heating installation, it was possible to find such a company’s website via the print directory, and consult the inspector’s services and price online, bypassing search engines such as Google and its complex algorithms. The telephone directory had a thematic and alphabetical order, combined with the possibility to buy additional advertising space.

Conducting research into the effects on energy consumption of blockchain-based applications such as bitcoin, I was triggered by the fact that many of the facilities making blockchain-mining1 possible are located in Georgia. Low energy prices and a relaxed taxation policy are said to be among the reasons why companies such as Bitfury locate their plants there.

After a three-day hike in the Caucasus Mountains, on the Georgian side of the border with Chechnya, we are invited to pitch our tent in the garden of Murati, a local farmer in a small mountain village. We are overwhelmed by the scenery and Murati’s hospitality. Many of the villages, thrown on the mountain flanks, have tower-like structures of some twenty meters high, making them all look fortified. They have no windows or doors on the ground floor.2

Murati invites us into his house to drink warm milk with his family and brings us cheese-filled bread. One of us speaks Russian. He inspects our backpacks, headlights and drinking bags. He tells us a 500 kilogram pig of his did not return to the house that night. The family is saddened.

In the evening, we see him taking his granddaughter by the hand. They walk to the highest point of the gravel road in front of his house and together watch the last light of the day fall on the snow-covered triangular peak of one of the Caucasus’ highest mountains.

I’m mistrusting my memory and look the passage up in the journal we kept. The village is called Zagar. The mountain is Mount Tetnuldi. The granddaughter’s name is Anna.

When I click through to one of the websites promising information on Georgia’s blockchain economy, I happen to stumble on a dark web-related website and access is denied.3

‘Mining’ is what is being done when data – a transaction – has to be added to the blockchain (which, in itself, is the sum of all previous transactions, added to each other as data). To do this, computers have to solve a complex mathematical puzzle, which is crucial for the trustworthiness of the system, but for which loads of energy is needed. Criticism on the effects of blockchain-mining is growing, as it has a gruesome effect on resources. In 2018, Andrew North writes, Bitfury used 28 million kilowatt-hours of electricity per month, equalling the consumption of 120,000 Georgian households.

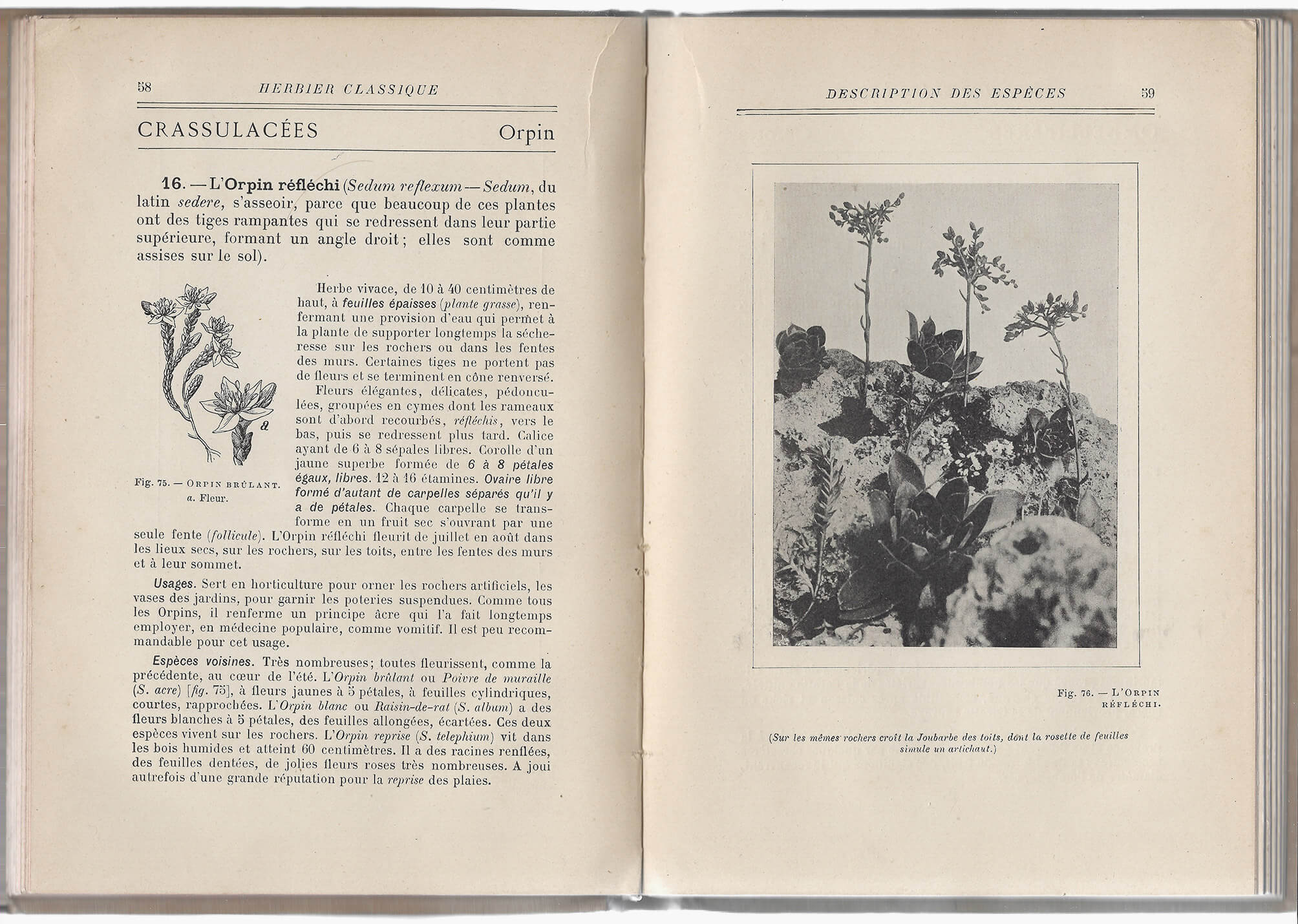

The Sedum reflexum grows on rocky soils and in crevices of walls. In L’herbier classique, it is depicted in two ways, just like the other plants in the book. This double portraiture is important, the author states in the introduction: ‘one consists of the reproductions of the photographs taken by the author of this book […]; the other, drawings made by excellent artists who observed the plants themselves, showing details photography can’t reproduce, highlighting aspects the photographs leave untouched. […] From this double representation, interesting comparisons can be made, highly enlightening from an artistic point of view, between the realistic aspect of nature’s “productions” and the interpretation thereof by the draftsman’ (5).

A detail not covered by the drawing of the sedum reflexum, is the presence of other species in the vicinity of the plant, a detail shown in the photograph and described in the caption: ‘The Common houseleek grows on the same rocks, with its rosette of leaves pretending to be an artichoke’ (59).

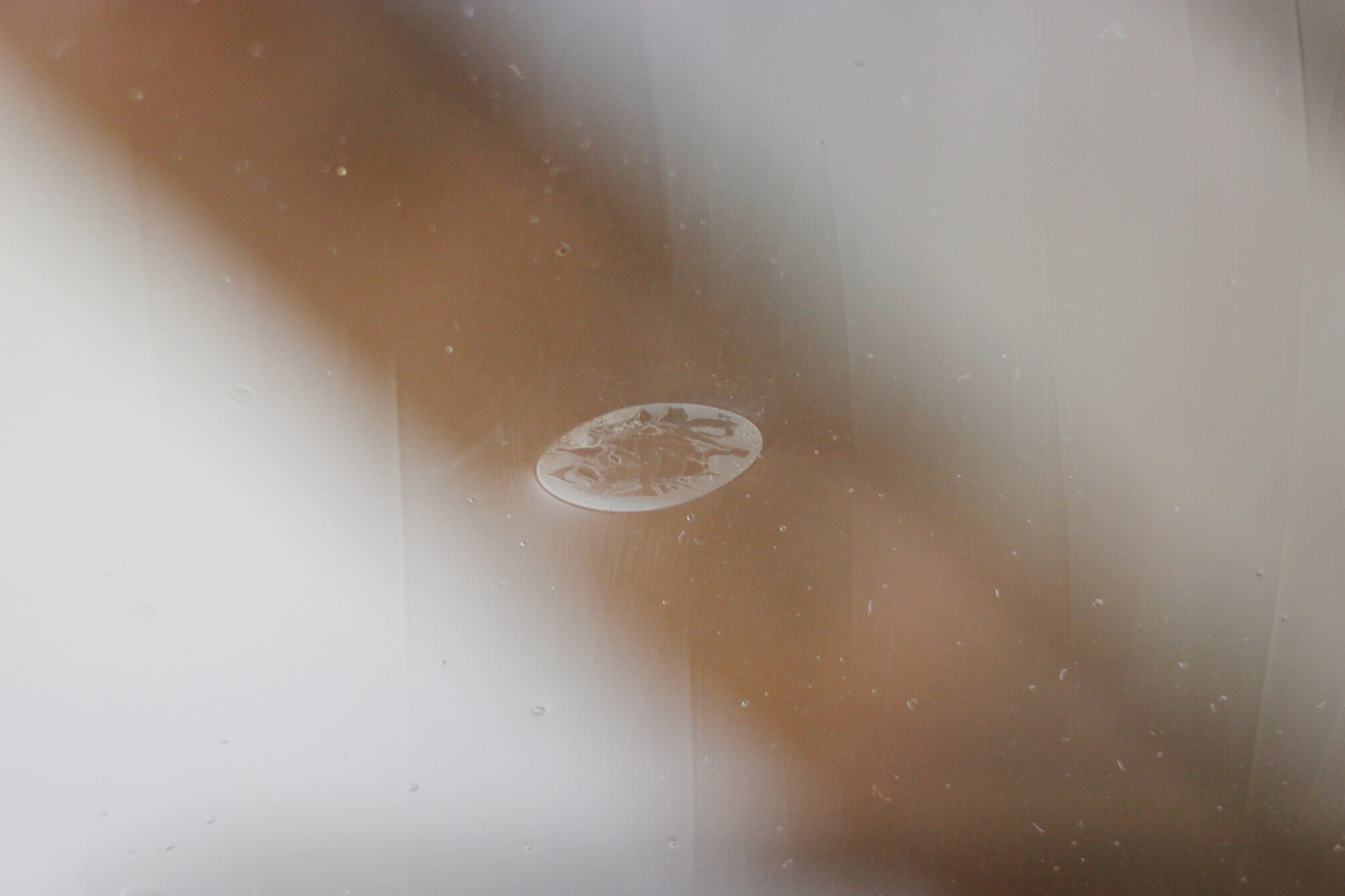

The oldest coin in the collection has darkened over time, but upon inspection, the text ‘AD USUM BELGII AUSTR’ (left) and the contours of a (female) head (right) can be discerned. A quick search learns it stems from the middle of the 18th century. The coin was made and used in the Austrian Netherlands, reigned by Maria Theresa, who is the one depicted. My mother recollects finding it in the backyard when she was a kid.

About 40 years later, the euro was introduced. The ringbinder with my mother’s coin collection was taken from the shelf. A dilemma came to the fore: we wondered if we should keep one of each existing Belgian coin and banknote and put them in the binder, alongside Maria Theresa, or if we should exchange them for the new European currency. The decision to keep a coin of five Belgian francs was not difficult to make, but as the amount raised, the answer was increasingly hard to give. This was an assessment of the old currency’s emotional and projected historical value, compared to its current financial worth. It was a decision based on investment principles.

To accentuate the value of the Maria Theresa kronenthaler of 1 liard, I put the coin on a pile of red post-it-notes when photographing it. Coins like these are sold on eBay for prices ranging from 0,70 euros to 16 euros.

It’s early spring. The pool is covered with a sheet of plastic. The deciduous trees are just leafing out. A tree stump serves as a placeholder for the diving board’s foot – it was customary to take it indoors for winter – and keeps people from kicking its threaded rods sticking up from the silex tiles that line the pool.

The upper right corner of the plastic frame is missing. It’s probably where the insect – now dead, dry and yellowish – got in. The frame was left behind in the laundry room overlooking the garden, the pool and the pool house. At the time it hadn’t been used for quite a while. Half empty, the water green.

In summer, when the wind dropped, horse-flies came. You could shake them off temporarily by swimming a few meters underwater.

Holding two cans of spray paint, a city employee walks through a sweet chestnut grove on the graveyard. He’s looking for potholes.

A white Mercedes van inserts in front of me in a traffic jam near Antwerp. The back of the van has been altered in several ways: a latch was added to the door,1 a footstep was bolted to the bumper, a couple of tie-wraps are holding up the lights on the left side.2 Traffic is moving slow. There is no Mercedes logo.3 Some parts have been retouched with white paint that differs slightly from the rest of the bodywork,4 not unlike a tipp-ex’ed document.

Maybe the original locking mechanism no longer functions, or, perhaps, the owner wants to add a padlock to the doors at night.

Maybe a corroded screw caused the lights to come loose, or a slight collision.

Someone might have stolen it. Mercedes stars are often stolen, although mostly from the hood.

Maybe to counter corrosion, to conceal a mark someone made on the van or to cover up a fixed dent.

Legislation concerning the publication of someone else’s licence plate on the internet and the demand to blur it, is somewhat ambiguous.

I’m taking a scan of a family photo album given to me after my grandmother passed away, wanting to write something about the marvelous portraits inside. The genealogy is only partly clear to me: I recognize my dad as a kid, my uncle, my grandmother, her brother in the laboratory he (said he) ran. He smelled of cigars and severe perfume. The older photographs present people I don’t know, but must be my ancestors. My grandmother told me stories1 that, historically, reach further back than the figures I recognize in the photographs. There are no names and no dates in the album. The first two pictures seem to be the oldest ones.2 I retract them from the album pockets in which they were slid to check if something is written on the backside. When I take the album away from the scanner’s glass plate, particles of leather, gold varnish and sturdy cardboard come loose. I place a sheet of paper on the glass plate and press ‘scan’ again.

Once she (my grandmother) went home from school, sick, with her bicycle. She studied to become a nurse. The school was in Brussels, about 60 kilometers from her native village M. The milkman’s van tipping over in front of my grandmother’s parental house. A milk covered street. My great-grandfather, physician and mayor at M. Something happened during the Second World War having to do with telephones or radios when she was still a kid.

As the hours passed, and while clouds continuously kept us from seeing stars and planets, we started to photograph the set-up used to launch this website. To highlight the umbrella that protected the gear from the unpredictable bursts of rain, we used a flashlight: during the thirty second long exposure, it was lit for two seconds. This proved to be enough to give the whole the feel of an untampered, realistic view. Meanwhile, the website was in all likelihood streaming a grey haze, as the telescope was pointed to the fleeting clouds and gradually spinning along with the earth’s movement to keep track of the same invisible celestial bodies. As we returned to the base, planet Jupiter had become visible to the naked eye.

In another exposure of the same length, we left the flashlight on for approximately eight seconds and pointed the beam a bit lower.

I must have driven past this rocky landscape about sixteen times, going back and forth between viewpoints and the house the parents of a friend let me stay in. On the last day, I left early for the airport, pulled into a lay-by, took my tripod and camera out of the trunk of the red Volkswagen Polo rental car and made two photographs.1 It was only when I got home, had the film developed, scanned it and was removing dust particles from the file, that I discovered the hand painted text on the rock: ‘PROIBIDO BUSCAR SETAS’.

A visit to the Royal Observatory of Belgium, in Ukkel. Most of the domes are damaged and need repairing. Only a few telescopes are in use. It is difficult to find a good spot from which to film the site. When we asked the people at the Royal Meteorological Institute – the Observatory’s neighbouring institution – if we could access their building’s roof to film the observatory, the answer was ‘no’.

I (M.D.C.) remember there was a fire nearby. We couldn’t see the flames, but a tall dark plume of smoke rose above the trees lining the site. We didn’t insist any longer and ceased our attempt to access the roof, hoping we might find a good spot to film the smoke with a dome in the foreground.

Kesteloot, J. Leerboek van Cosmografie voor Middelbaar en Lager Normaal Onderwijs (derde vermeerderde uitgave). Brugge: Firma Karel Beyaert, 1948.

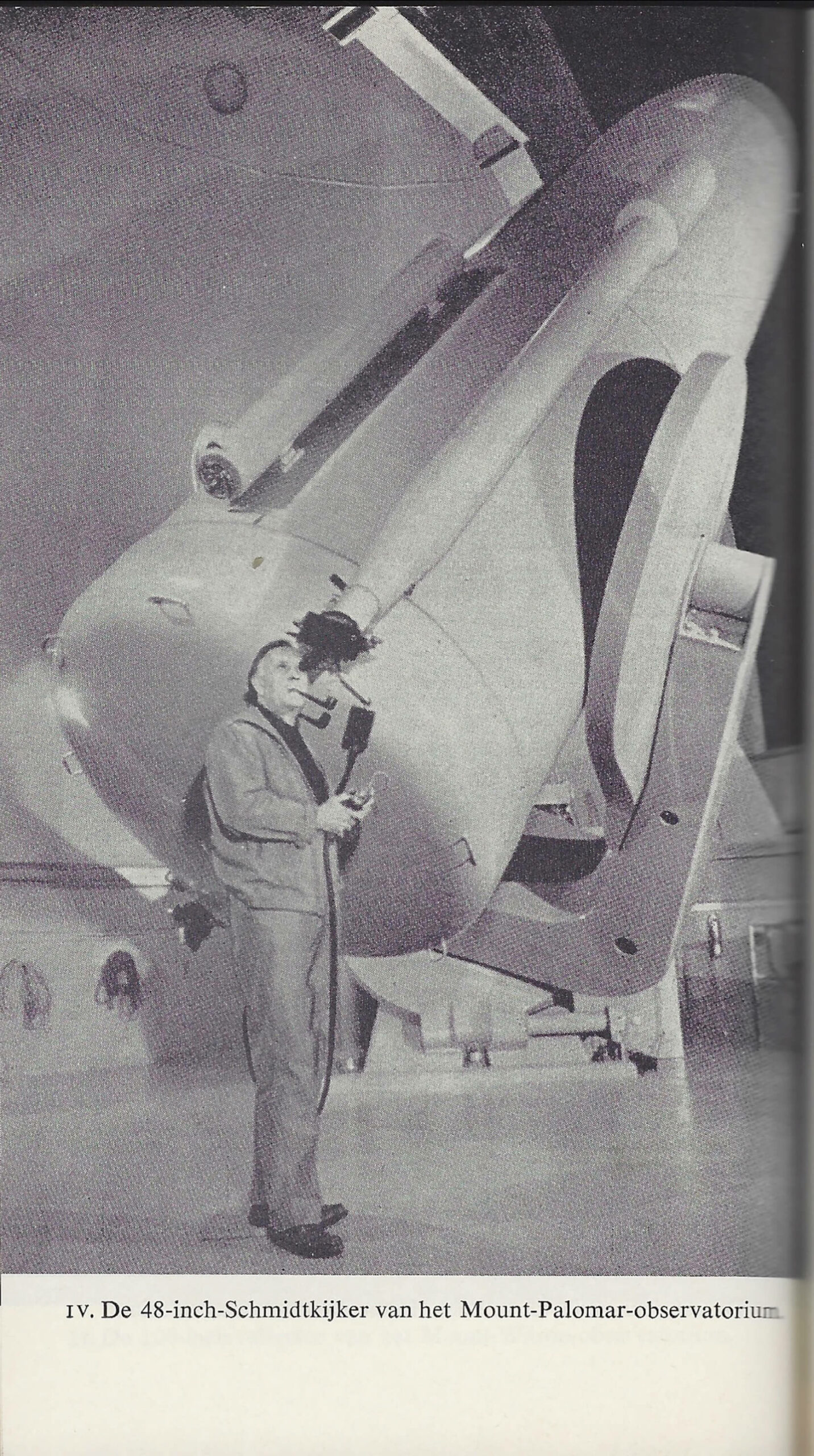

The 48-inch Oschin Schmidt, a renowned reflecting telescope at Palomar Observatory, California, was used for the Palomar Observatory Sky Survey (POSS), published in 1958, one of the largest photographic surveys of the night sky.

Based on the man’s pipe shadow’s direction, thrown onto the telescope, there is reason to believe an off-camera flash was used to make the picture.

‘The masons in training pour a concrete slab and build four walls upon it in a stretcher bond. Then the block comes to our department and the students in the course Electrical installer (residential) can grind channels and drill cavities in it.’

[…]

‘It’s not always a success from the outset, but they learn quickly.’

[…]

‘Never grind horizontally, always vertically. Diagonally if there is no other way.’

[…]

‘Two fingers wide.’

[…]

‘After this it goes to the sanitary department. After the bell drilling, the demolition hammer follows and the masons make us a new block.’

Competentiecentrum VDAB, Wondelgem, July 2019.

First published in A+ Architecture in Belgium, A+ 279, Schools (August, September 2019), https://www.a-plus.be/nl/tijdschrift/schools

The torn off section of roofing on the grass has part of a text carved in it: ‘UDI’ and ‘EN’ are still legible. It must have come from another roof; the one shown in the photograph has no missing sections, nor visible repairs.

The roofing that is still on the garage shows a drawing of some kind. A floorplan for a squarish building with a supporting column along each side, or the layout for a tactical explanation, perhaps.

Seven very similar and rudimentary buildings take in a trapezoid plot of land in Gilly. They are located between the school on the Rue Circulaire and the houses along the Rue de l’Abbaye. The structures are built of orange brick, concrete structural elements, whitish steel gates and roofing. Every garage has its own number, hand-painted in white on the concrete lintel above each gate. In summer the roofing gets hot and soft.

Until recently, for as long as I could remember, the packaging of Tabasco® Pepper Sauce had been unchanged. On the front of the packaging, there is a photograph of a bottle of Tabasco®, scale 1:1, against an orange background.As far as packaged goods go, this is a highly idiosyncratic and quirky example.

The background colour approximates the colour of the liquid inside the bottle, resulting in as good as no contrast. Moreover, as the image of the bottle is scale 1:1, the packaging becomes kind of unnecessary and superfluous, also because the life-sized image of the bottle is the only way information is given to the customer: there are no additional slogans, no repetition of the brand name, no props and no decor. The image of the bottle advertises the bottle. It seems to add nothing the bottle could not do by its own (like a bottle of wine does).

What makes the packaging truly stand out, however, is the fact that the image of the bottle is not positioned vertically, but is slightly askew. It seems to be the result of a design error, and has an amateur feel to it. The decision to keep it as such and not correct it up until today, is, however, a stroke of genius. The non-vertical positioning alters the relation of the image of the bottle to the bottle inside: as the box is standing on a shelf, the tilted image of the bottle undermines its representational superfluousness.

The door leading to the kitchen has a section in stained glass. The other day, I took a closer look at one of the spots on it, which I had half-consciously registered every time I passed it. On two square meters, there are three of them. All are oval in shape. Two of them seem to be flat bubbles of air, haphazardly produced during the manufacturing of the glass, I imagine. The third one, however, is peculiar. It drew my attention because it appeared to represent something. Upon closer investigation, it seemed to allude to different things. A model ship, like the ones in glass bottles. A dragon, like the one used on the Welsh national flag. A tailed, devilish figure riding a cloud-like motorcycle. What skills the glass worker must have had, to produce an image in a glass covered air capsule like this. I closed the door softly, as the microwave’s signal sounded.

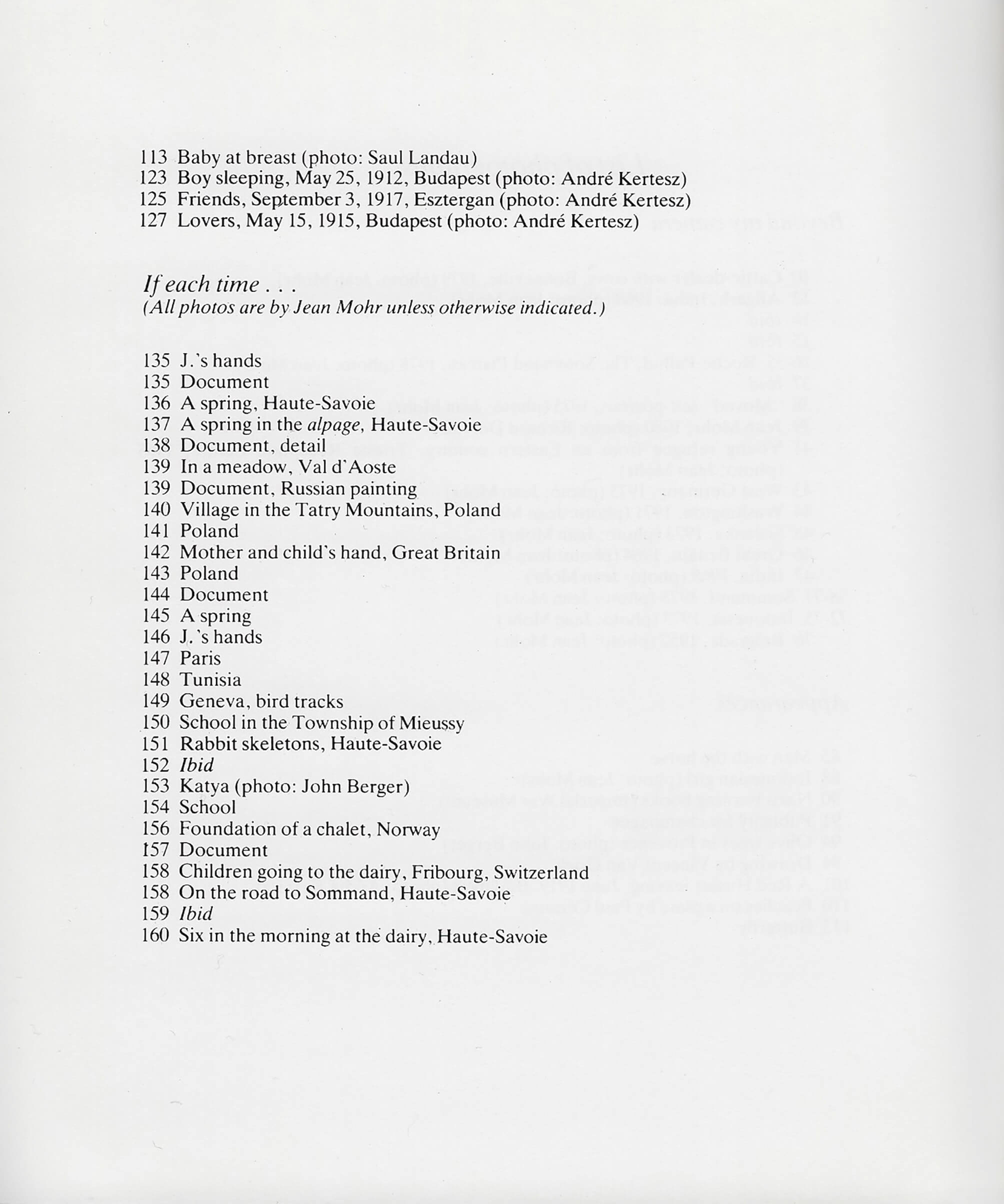

In John Berger and Jean Mohr’s groundbreaking book Another Way of Telling, the index at the end gives information on the images printed throughout the book. Most of them are Jean Mohr’s. In the section ‘If each time…’ – a wordless sequence of images which aims to develop an alternative way of telling a story – some images are referenced as ‘documents’. The information is sparse. On page 138, the index states, there is a ‘Document, detail’. It features a closeup of a knitted piece of fabric. It appears to be the same picture as seen on the first page of the section (p. 135), where it is printed beneath another image – a photo by Mohr of hands knitting. On this occasion, the image is indexed as ‘Document’.

Berger, J. & J. Mohr. Another Way of Telling. London / New York: Writers and Readers, 1982.

During the one day course Safety and Avalanches, teacher G.T. shows pictures of different manifestations of snow and ice. If one learns to read them, one can deduce the wind direction when hiking or skiing in mountainous terrain. Wind direction is crucial for assessing the stability of the snow. G.T.’s examples are of Austrian origin. He speaks about ‘Anraum’: displaced snow can get stacked horizontally against an object, such as a tree or a cross. The snow ‘grows and builds into the wind’. Counter-intuitively, the snow points to the side the wind is coming from. One can expect dangerous terrain in the direction of the ‘unbuilt’ side of the object.

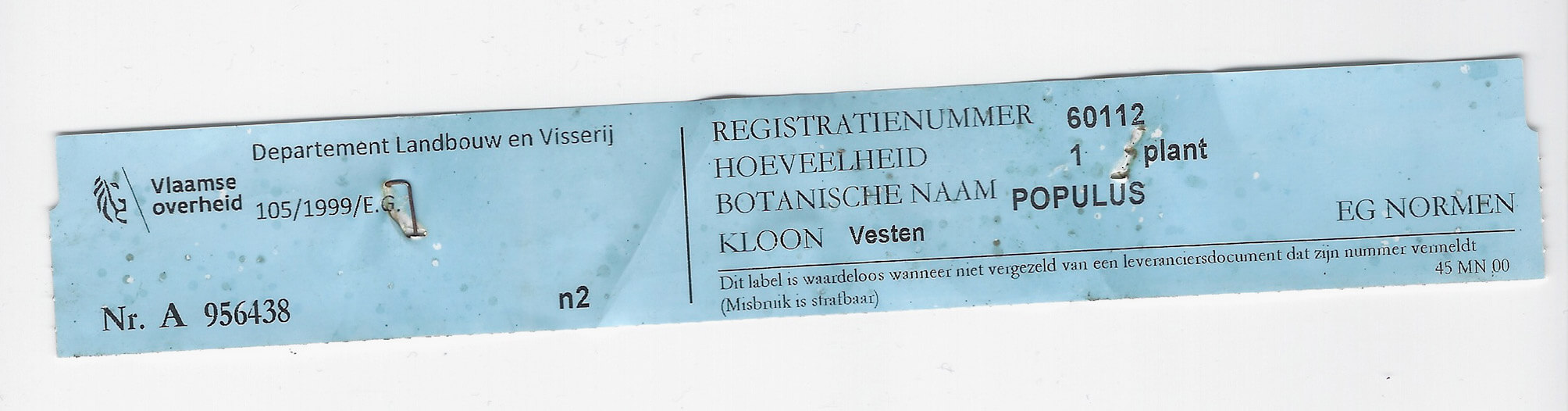

A Sunday stroll near my parents’ house. Along one of the roads between the fields, old poplars have been felled. Young trees have been planted. Each one has a baby blue coloured label, identifying them as Poplar tree, and, more specifically, the ‘Vesten’ cultivar. This cultivar is planted since it is one of the cultivars known for its resistance with regards to bacteria, diseases and insects. The tags on the trunks have staples keeping them together. They’re like bracelets. Come spring, the expanding diameter of the fast growing poplar species’ trunk will tear them apart.

Steenackers, M., Schamp, K., & De Clercq, W. (2018). De INBO variëteiten van populier, een aanwinst voor de Europese populierenteelt. Silva belgica : tijdschrift van de koninklijke belgische bosbouwmaatschappij = bulletin de la société royale forestière de belgique, N°4/2018, 40-47. [5].

https://purews.inbo.be/ws/portalfiles/portal/15044340/Dossier_populier_INBO_KBBM.pdf

Yesterday I had my shoulder checked by a radiologist. He took an ultrasound and saw some minor inflammation of my right subscapularis. After giving me some advice – ‘we could give you a shot of cortisone in the shoulder. It would relieve you from your pain for six weeks and then, without proper exercise, you’d be back where you are now’– he walked towards the door. ‘I propose you do this exercise thirty times, three times a day.’ The radiologists put his right hand on the doorframe, his arm stretched, the weight of his body on it and then leaned forward and back again, while keeping his arm stretched. ‘This will increase the muscles around the sore subscapularis. It will take months.’ After giving me his advice, he sent me back into the dressing room. I put my shirt back on and went into the waiting room. The nurse called out my name, charged me 14,00 EUR and gave me a card. ‘This code will allow you to look at the images of the ultrasound at home’, she said.

Today I entered the code and password and – instead of my shoulder – found the röntgen-images of someone else’s broken heel.

Depending on the perspective one chooses to look at the address, the house is adorned or not. The perspective from the main road is an image made in August 2020, the website (Google Maps) says. Our car is in front of the garage. It must be the end of August. We drive home from the hospital with the newborn, who doesn’t stop crying. Maybe I tightened the belts in the car seat too much. Arriving at our house, we see the slogans and decorations friends have hung at our front door. On the sill of the neighbour’s first floor window, there’s a brick that must have fallen from the second floor facade.

Besides the scale indicating the length in centimeters, and the marks made by using it, a folding ruler displays other marks. These are the marks found on the weber broutin www.weber-broutin.be folding ruler, from left to right:

- 2m (in a frame, between 1cm and 2cm); indicating the total length of the folding ruler.

- a hexagon, barely visible, punched into the wood (between 2cm and 3cm); unknown signification.

- LUXMA (in a frame, between 4cm and 5cm); the manufacturer of the folding ruler (different from the company who ordered the folding ruler, their (the company’s, i.c. weber-broutin’s) name is printed on the sides of the ruler, and is only readable when the ruler is folded together for at least 50% (=1m).

- III (in an oval, between 6cm and 7cm); indication of the preciseness of the scale in centimeters, with ‘I’ in roman numbers meaning the most precise, and ‘IV’ in roman numbers meaning the least precise. (It is therefore not entirely certain that the ‘III’ on weber-broutin’s folding ruler can actually be found between 6cm and 7cm.)

- D 99 (in an oval, probably between 7cm and 8cm, see argument mentioned above); unknown signification.

- 1.1.60 (in an oval, probably between 7cm and 8cm, beneath D 99), signification unknown.