What constitutes a ‘document’ and how does it function?

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the etymological origin is the Latin ‘documentum’, meaning ‘lesson, proof, instance, specimen’. As a verb, it is ‘to prove or support (something) by documentary evidence’, and ‘to provide with documents’. The online version of the OED includes a draft addition, whereby a document (as a noun) is ‘a collection of data in digital form that is considered a single item and typically has a unique filename by which it can be stored, retrieved, or transmitted (as a file, a spreadsheet, or a graphic)’. The current use of the noun ‘document’ is defined as ‘something written, inscribed, etc., which furnishes evidence or information upon any subject, as a manuscript, title-deed, tomb-stone, coin, picture, etc.’ (emphasis added).

Both ‘something’ and that first ‘etc.’ leave ample room for discussion. A document doubts whether it functions as something unique, or as something reproducible. A passport is a document, but a flyer equally so. Moreover, there is a circular reasoning: to document is ‘to provide with documents’. Defining (the functioning of) a document most likely involves ideas of communication, information, evidence, inscriptions, and implies notions of objectivity and neutrality – but the document is neither reducible to one of them, nor is it equal to their sum. It is hard to pinpoint it, as it disperses into and is affected by other fields: it is intrinsically tied to the history of media and to important currents in literature, photography and art; it is linked to epistemic and power structures. However ubiquitous it is, as an often tangible thing in our environment, and as a concept, a document deranges.

the-documents.org continuously gathers documents and provides them with a short textual description, explanation,

or digression, written by multiple authors. In Paper Knowledge, Lisa Gitelman paraphrases ‘documentalist’ Suzanne Briet, stating that ‘an antelope running wild would not be a document, but an antelope taken into a zoo would be one, presumably because it would then be framed – or reframed – as an example, specimen, or instance’. The gathered files are all documents – if they weren’t before publication, they now are. That is what the-documents.org, irreversibly, does. It is a zoo turning an antelope into an ‘antelope’.

As you made your way through the collection,

the-documents.org tracked the entries you viewed.

It documented your path through the website.

As such, the time spent on the-documents.org turned

into this – a new document.

This document was compiled by ____ on 10.02.2022 14:07, printed on ____ and contains 33 documents on _ pages.

(https://the-documents.org/log/10-02-2022-3794/)

the-documents.org is a project created and edited by De Cleene De Cleene; design & development by atelier Haegeman Temmerman.

the-documents.org has been online since 23.05.2021.

- De Cleene De Cleene is Michiel De Cleene and Arnout De Cleene. Together they form a research group that focusses on novel ways of approaching the everyday, by artistic means and from a cultural and critical perspective.

www.decleenedecleene.be / info@decleenedecleene.be - This project was made possible with the support of the Flemish Government and KASK & Conservatorium, the school of arts of HOGENT and Howest. It is part of the research project Documenting Objects, financed by the HOGENT Arts Research Fund.

- Briet, S. Qu’est-ce que la documentation? Paris: Edit, 1951.

- Gitelman, L. Paper Knowledge. Toward a Media History of Documents.

Durham/ London: Duke University Press, 2014. - Oxford English Dictionary Online. Accessed on 13.05.2021.

At a dental practice, the white Alligat®-powder is mixed with the right amount of water to get a mouldable dough that is pressed upon a patient’s teeth. After thirty seconds, the Alligat®-dough stiffens and takes on a rubber-like quality. At that point, still white, it must be removed from the patient’s mouth. Over the next few hours, the mould turns increasingly pink as the substance becomes less humid. Now, it can be used as a mould to create a positive master cast of the patient’s teeth.

Outside the dental practice, the powder’s possibilities remain to be fully explored.

First published as part of De Cleene De Cleene. ‘Amidst the Fire, I Was Not Burnt’, Trigger (Special issue: Uncertainty), 2. FOMU/Fw:Books, 25-30

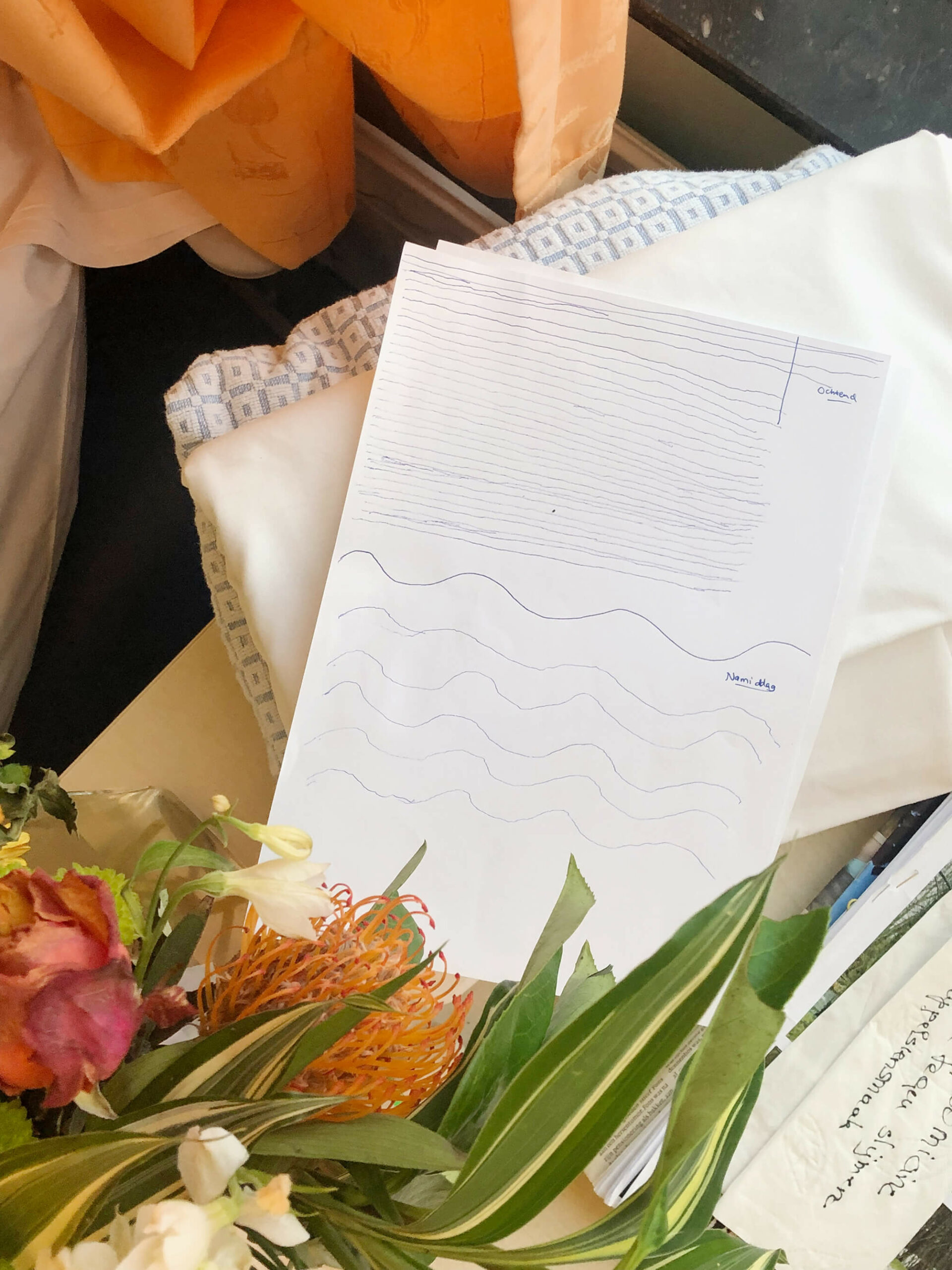

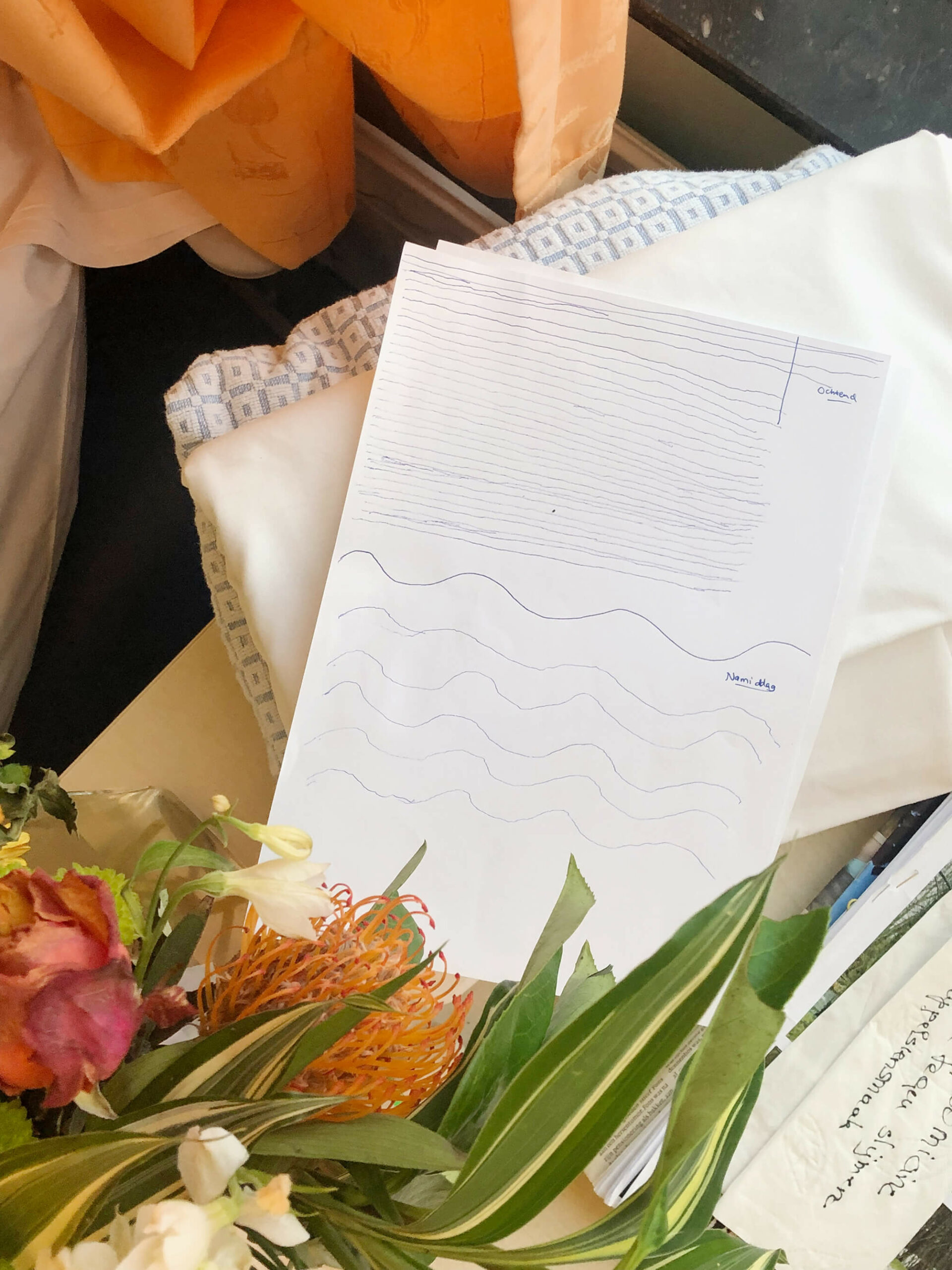

On a pile of fresh hospital sheets, near the radiator, the tangerine curtains and the black marble window sill (the window looks out over the parking lot), underneath the two-day-old bouquet of flowers and next to a pile of magazines with a handwritten note on top (about a syrup that relieves slime and tastes like oranges), lie two sheets of paper.

Earlier that day the physiotherapist had come by. Twice. Once in the morning and once in the afternoon. He had each time drawn the first line, as an example. A straight line in the morning, a curvy line in the afternoon.

With a ballpoint pen my grandfather, who is recovering from an accident, diligently copied the examples (31 in the morning, 5 in the afternoon).

A year ago, mid-August, just before sunrise, the mostly unlit office buildings line the road that leads to the underground parking. I turn off the ignition. I’m in F36. The walls are painted pink. Looking for the exit, I take the escalator and get stuck in an empty shopping mall. The music is playing but all the shops are closed off with steel shutters. So are the exits. I’m out of place. In keeping early customers out, the mall is keeping haphazard visitors in. I’m back in the parking lot. The elevator is broken. I take the stairs and walk by a homeless man, sleeping. There’s shit on the floor. I open the door that leads out of the stairwell. It slams shut behind me. There’s no doorknob. I find myself on a dark floor between mall and parking lot. People are sleeping; some are awake. Heads turn toward me. I start walking slightly uphill towards where I think I might find an exit, or an entrance. The scale of the architecture has shifted from car (F36) and customer (the closed mall) to truck. I find myself amidst the supply-chain. It takes five minutes, maybe fifteen, maybe more to get out and see the office buildings towering over me in the first light of day.

At the Tunis Institut National du Patrimoine, the sand-covered floor has traced Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker’s movements to Steve Reich’s Violin Phase. The venue empties out. It is dark and the way back to the hotel through the medina is labyrinthian and eerie. It has been a couple days since we arrived, and I have managed to make a mental image of the inner city by memorizing some waymarks – intersections, buildings, shops – coupled to a direction. Sometimes, a newly entered street would give out to such a waymark – a peculiar sensation: a flash of spatial insight, like a crumpled ball of paper unfolding. The narrow streets turn and turn. Some passages are closed at night. I must improvise a route, but the basic mental structure to do so is missing. Shopkeepers have moved their goods inside.

I have no sense of orientation. I can’t estimate distances nor can I tell north from south. Everything is scaleless. My highly simplified scheme of the city’s layout gets us to our destination. The functional interpretation of Tunis differs completely from the actual Tunis. It is a different city we crossed, and made while crossing.

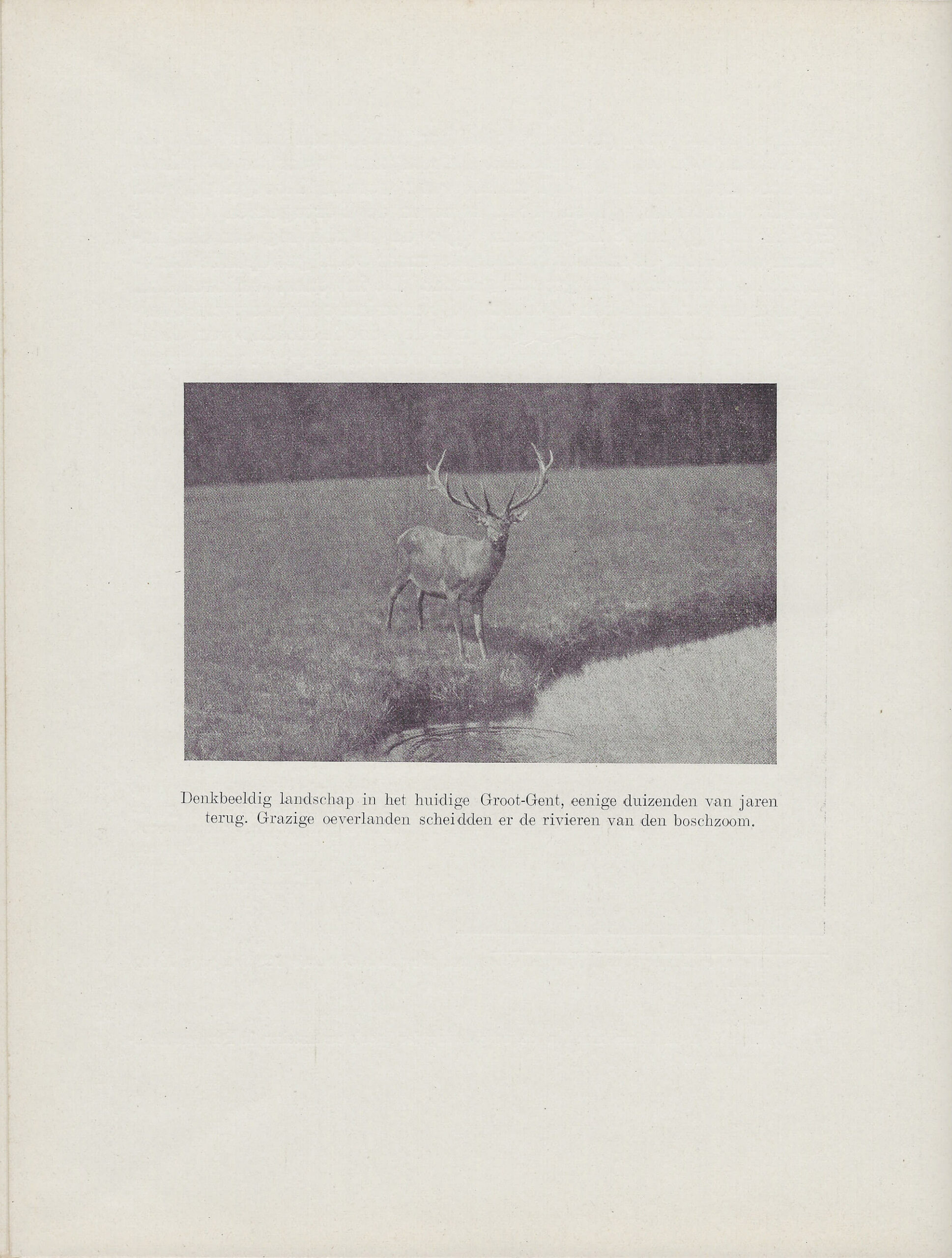

(‘Imaginary landscape in the actual greater Gent, some thousands of years ago. A grassy riparian zone separates rivers from the edge of the forests’)

Imagine a deserted city of Gent, overtaken by nature, Thiery asks the reader in his book Het woud (The Forest). After fifty years, you return to the city. Buildings have collapsed, streets are overgrown. It has become an impenetrable, dense forest, except for the river on which the reader makes his or her way through it. In the first half of the twentieth century, Leo Michel Thiery made one of Belgium’s first botanical gardens for educational purposes. In the middle of an industrialized quarter of the city of Gent, the garden presented different sceneries. There were landscapes from the Alps, dunes, the Ardennes, steppe. Besides sceneries with chalk-, loam-, marl- and sand-based vegetation, there were forests, grasslands and swamps.

After his death, Thiery’s garden decayed. Decades later, it was restored, with the Alps, dunes, the Ardennes and steppe now classified as a protected view.

Thiery, M. Het woud. Een proeve van plantenaardrijkskunde. Gent: De Garve, s.d., p. 14

In between two cities along the Belgian coast, water has run from the dunes (and the Second World War Heritage site scattered among them), underneath the coastal road and tram rails, to the beach. It has formed a small S-shaped estuary, bound to disappear due to the increasingly harsh wind coming from the coast of Britain, blowing North-easterly, and hammering down on the levee. The vibrations of the empty Ostend-bound tram passing just before the photograph was taken, had no visible impact on the estuary.

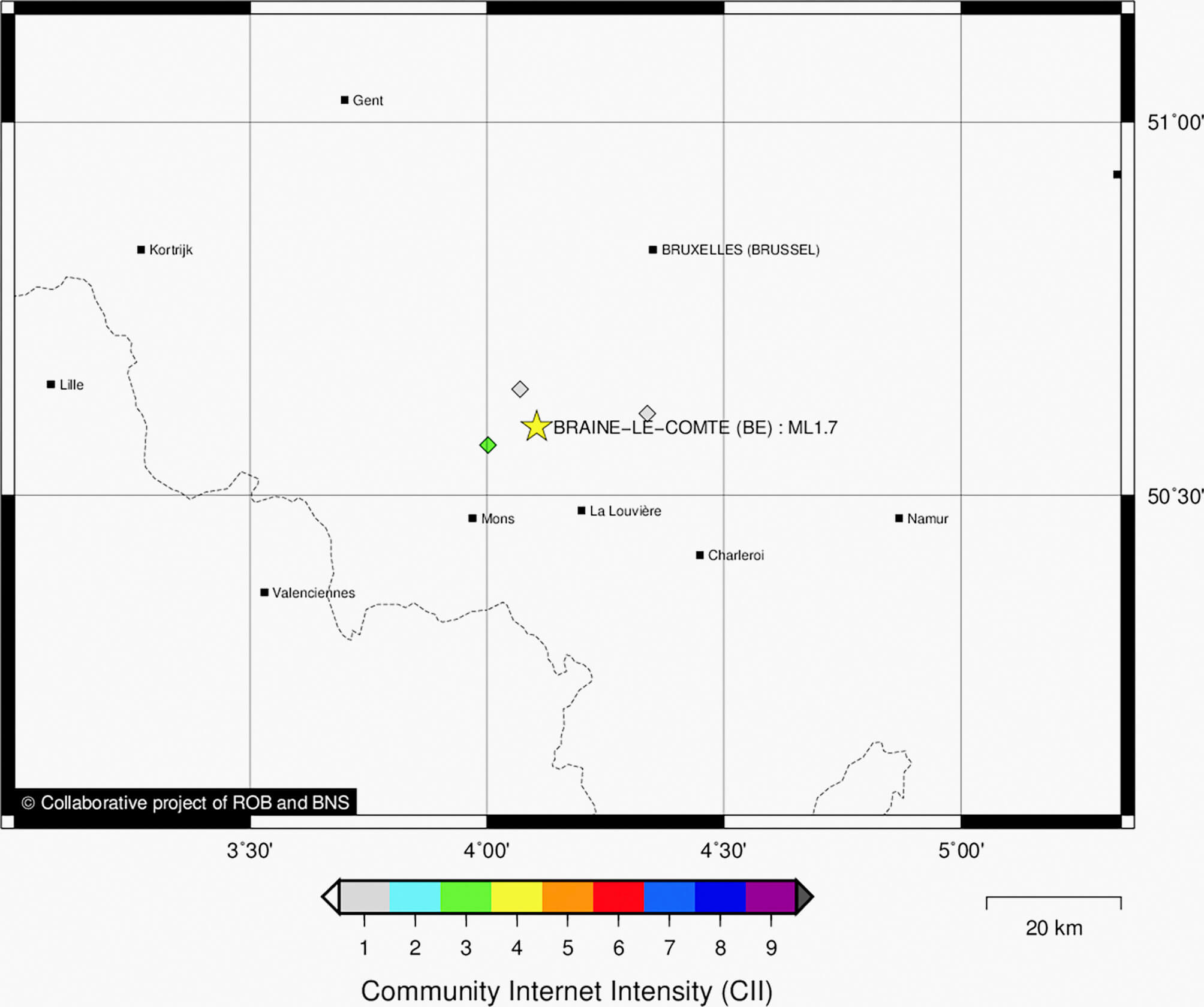

On May 6th 2020, 14h06 and 31 seconds, the Belgian Seismological Institute records an earthquake with a 1,7 magnitude in the region of Braine-Le-Compte. Three reactions from people in the neighbourhood, filed by the Institute, confirm the official seismological recordings. The Institute’s website classifies the earthquake as a ‘quarry blast’.

http://seismologie.be/nl/seismologie/aardbevingen-in-belgie/en130qj1o

The road down from the top of Mount Vesuvius, at Atrio Del Cavallo. The sun sets. The last tourist bus has headed down. Then the headlights of the guardian’s car swing their way down. It must be freezing. I am holding an orange-sized piece of petrified lava, probably stemming from the 1872 or 1944 eruption. A kilometer further down the road, the old Observatory is empty. Nowadays, monitoring seismic changes is done in a research centre in the city of Naples. Their seismographic registrations can be followed online, in real time. Two headlights swirling along the slopes, underneath me, are coming upwards.

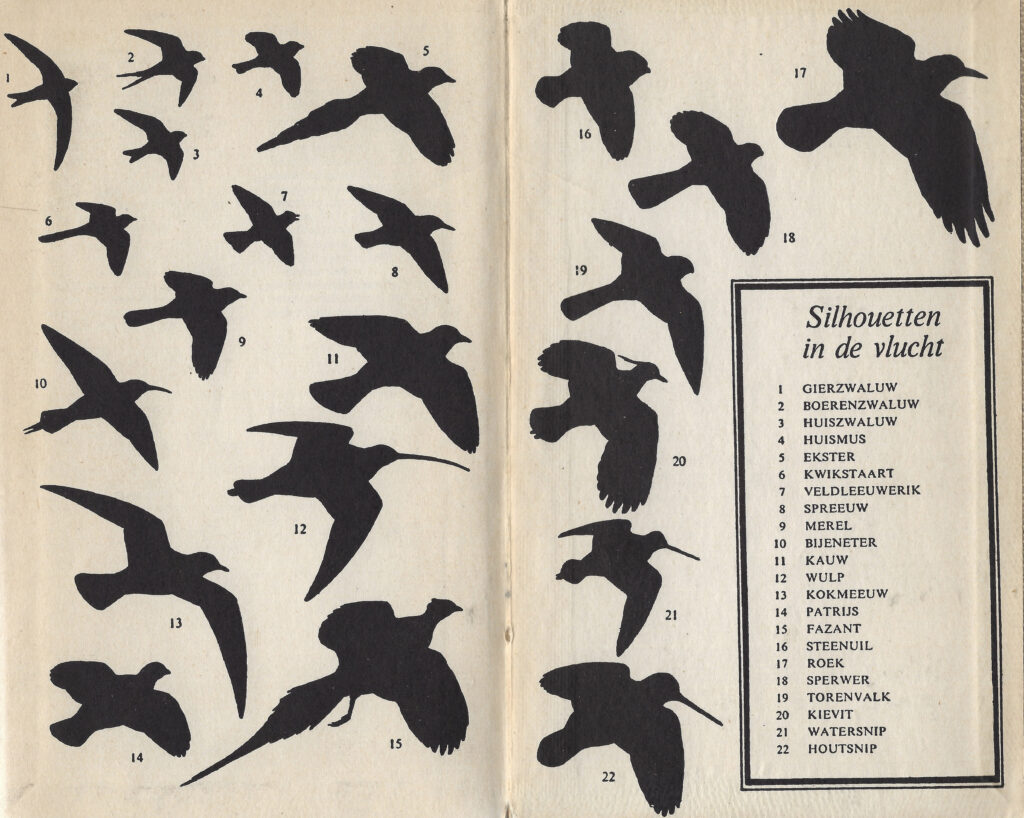

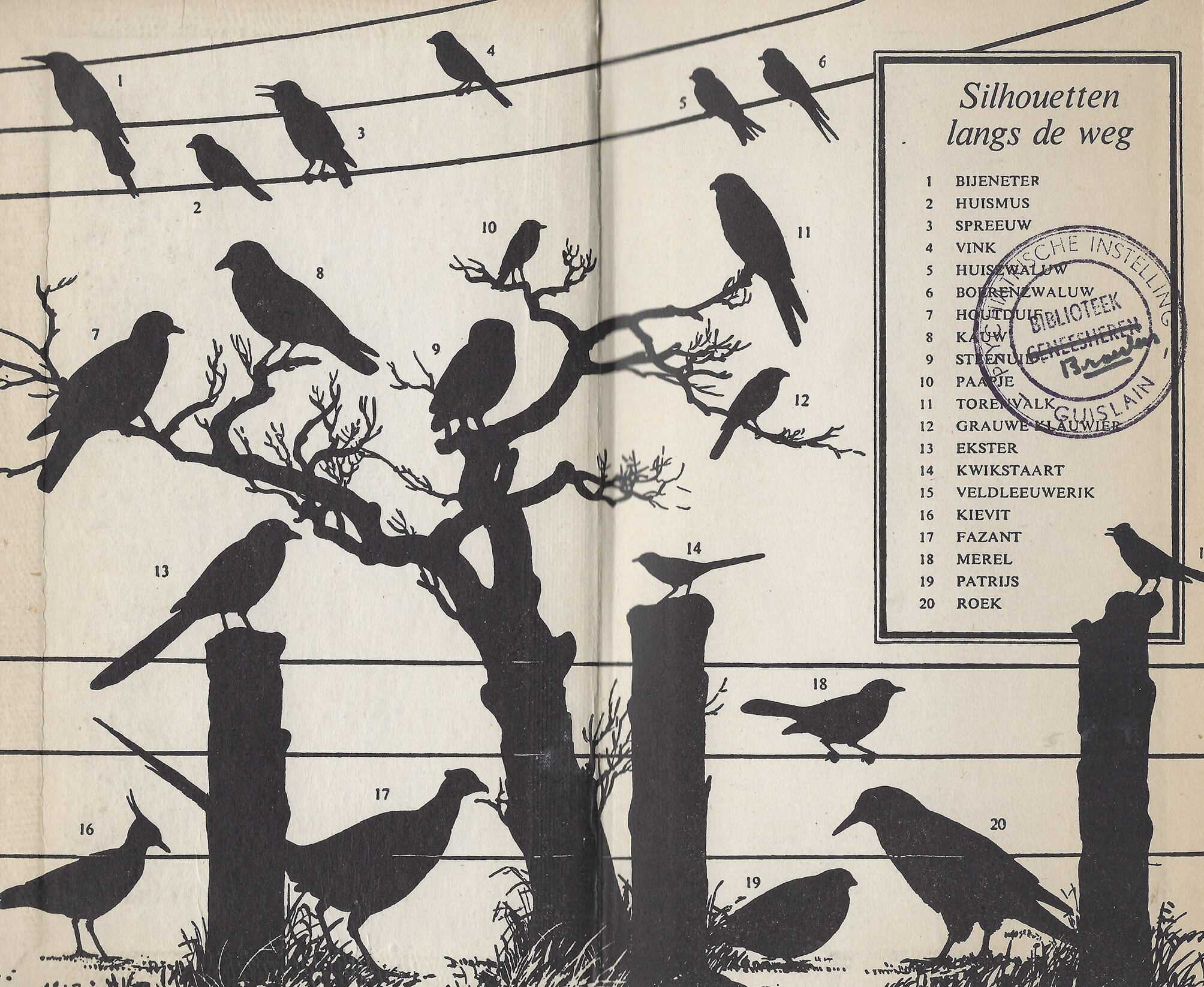

This is the spread one sees upon opening the bird field guide that once stood, as the stamp indicates, in the library of a psychiatric institution.1 It shows birds’ silhouettes, as they can be seen beside the road.

The drawing has a kind of Hitchcock feel to it.2 The birds seem to be spying on each other, as they also seem to be spying on the unsuspecting passer-by.

The composition of the scene is marvelous. The electric wires, the tree, the wire fence, the double framed list with the birds’ names, handsomely positioned in a birdless patch, at once superimposed on the telephone wires, and pushed to the background by the skylark.

Imagine seeing this scene. What are the odds: to see the silhouettes of Europe’s twenty most common species of birds in one glance, from your car’s window, as you are driving home at dusk.

Before closing the book, the last spread seems to show the birds fleeing, maybe attacking.3

The stamp indicates that, at the psychiatric institution, the book was part of the sublibrary for the Catholic Brothers of Charity. The crossed-out part indicates that there was also a separate physicians’ library, to which the book might have originally belonged.

On the web, discussions on whether Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds (1963) was shot in colour or in black and white, abound.

Peterson, R.T., Mountfort, G. & P.A.D. Hollom. Vogelgids voor alle in ons land en overig Europa voorkomende vogelsoorten (J. Kist, transl.). 3d ed. Amsterdam/Brussels: Elsevier, 1955.

Near Avenue 61 on an artificial island close to Seef, a truck is being towed after the driver lost control over the vehicle and flipped it onto its side. A warm wind blows in from the Persian Gulf.

A police officer signals us to come closer. ‘Why are you taking pictures?’ he asks. ‘This is just an accident. You have to delete the pictures from your phone. Now.’ After checking the pictures-folder on our phones, he gets in his car, drives a few metres, stops the car and rolls down his window. ‘And don’t do it again!’ he yells. Then he drives off, raising a cloud of sand in his wake.

Photograph taken and recovered from my trash bin on 18.12.2020.

In June, 2014, a severe hailstorm hit Belgium. Warnings were broadcast. A football game between the national teams of Belgium and Tunisia was paused. The morning after, there were small dents in the hood and the roof of the car, each a square centimeter in size, some 10 centimeters separated from each other. The storm didn’t get a name.

Assessing the damage, the insurance company’s expert took the dents into account to establish the wreck’s worth.

A year ago, mid-August, just before sunrise, the mostly unlit office buildings line the road that leads to the underground parking. I turn off the ignition. I’m in F36. The walls are painted pink. Looking for the exit, I take the escalator and get stuck in an empty shopping mall. The music is playing but all the shops are closed off with steel shutters. So are the exits. I’m out of place. In keeping early customers out, the mall is keeping haphazard visitors in. I’m back in the parking lot. The elevator is broken. I take the stairs and walk by a homeless man, sleeping. There’s shit on the floor. I open the door that leads out of the stairwell. It slams shut behind me. There’s no doorknob. I find myself on a dark floor between mall and parking lot. People are sleeping; some are awake. Heads turn toward me. I start walking slightly uphill towards where I think I might find an exit, or an entrance. The scale of the architecture has shifted from car (F36) and customer (the closed mall) to truck. I find myself amidst the supply-chain. It takes five minutes, maybe fifteen, maybe more to get out and see the office buildings towering over me in the first light of day.

‘You see?!’

[The man points at the waybill1 on the floor behind the glass door that closes off the abandoned and dismantled hall.]

‘It used to be here, I’m sure.’

[He looks around.]

‘I’m sure.’

[He turns towards me.]

‘Are you also here for the Leen Bakker?2 This used to be a Leen Bakker. I just looked it up on their website. They are open from 9 to 6 today.’

[He points at the waybill again.]

‘It was here. I remember well. It’s been years. But it’s here.’

[He walks away.]

‘I’ll look around.’

The waybill documents the transport of a 30m3 container filled with approximately 5000 kg of waste from this branch of Leen Bakker to a scrap processing company in nearby Ninove. They take care of scrap, both ferrous and non-ferrous metals. They also have a recognized depollution center for end-of-life vehicles.

A chain of furniture and interior stores with branches in the Netherlands, Belgium and the Caribbean part of the Kingdom of the Netherlands.

Depending on the perspective one chooses to look at the address, the house is adorned or not. The perspective from the main road is an image made in August 2020, the website (Google Maps) says. Our car is in front of the garage. It must be the end of August. We drive home from the hospital with the newborn, who doesn’t stop crying. Maybe I tightened the belts in the car seat too much. Arriving at our house, we see the slogans and decorations friends have hung at our front door. On the sill of the neighbour’s first floor window, there’s a brick that must have fallen from the second floor facade.

I’m taking a scan of a family photo album given to me after my grandmother passed away, wanting to write something about the marvelous portraits inside. The genealogy is only partly clear to me: I recognize my dad as a kid, my uncle, my grandmother, her brother in the laboratory he (said he) ran. He smelled of cigars and severe perfume. The older photographs present people I don’t know, but must be my ancestors. My grandmother told me stories1 that, historically, reach further back than the figures I recognize in the photographs. There are no names and no dates in the album. The first two pictures seem to be the oldest ones.2 I retract them from the album pockets in which they were slid to check if something is written on the backside. When I take the album away from the scanner’s glass plate, particles of leather, gold varnish and sturdy cardboard come loose. I place a sheet of paper on the glass plate and press ‘scan’ again.

Once she (my grandmother) went home from school, sick, with her bicycle. She studied to become a nurse. The school was in Brussels, about 60 kilometers from her native village M. The milkman’s van tipping over in front of my grandmother’s parental house. A milk covered street. My great-grandfather, physician and mayor at M. Something happened during the Second World War having to do with telephones or radios when she was still a kid.

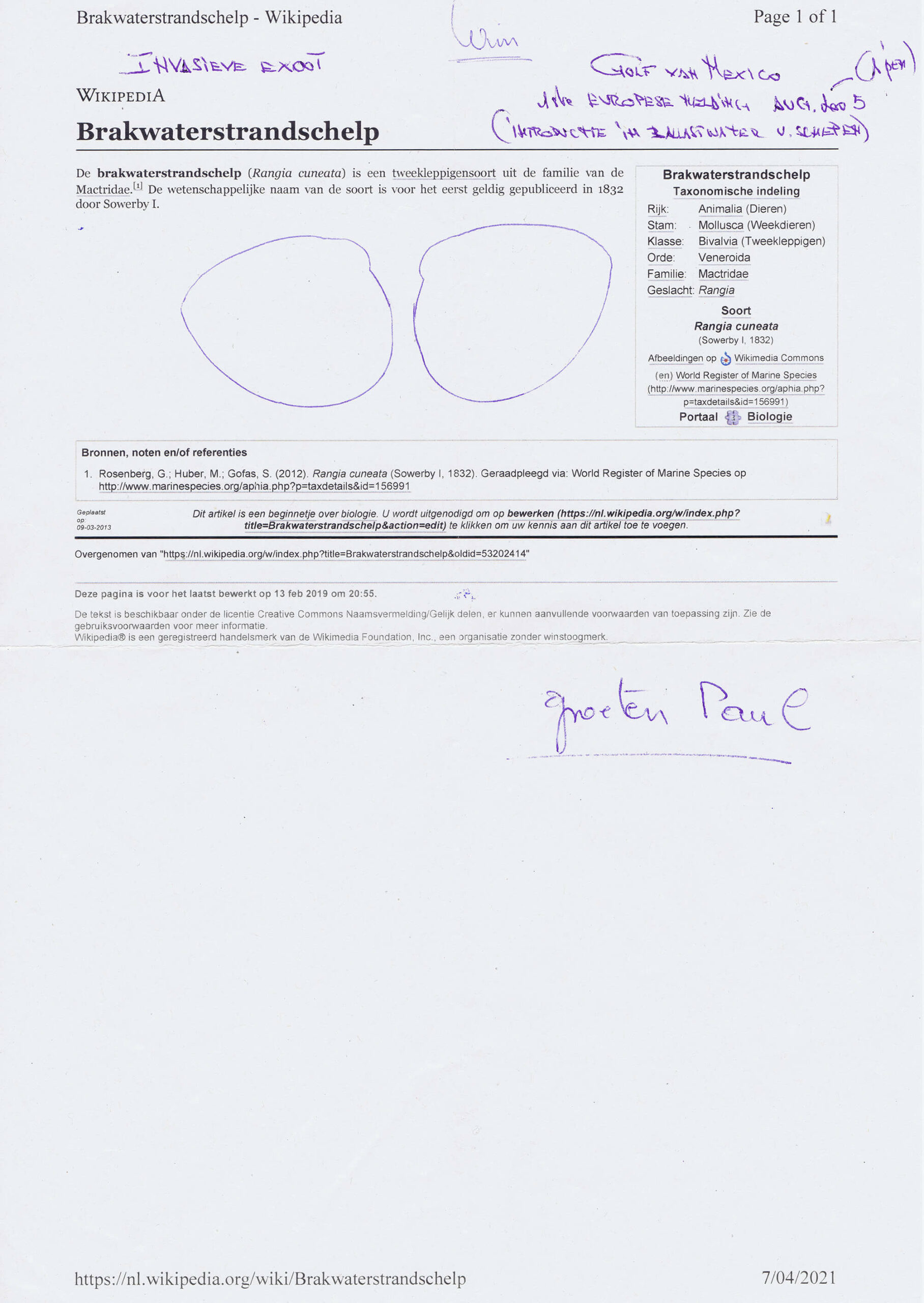

Halfway March my dad started finding empty clam shells on the banks of the Zuidlede along the pasture where he used to herd sheep. He had never seen this type of clam before. There were easily seventy of them along a hundred metre stretch of riverbank.

He brought two specimens to someone he knows in the neighbouring provincial domain. She would look into it, she said, and that she would probably pass it on to someone at the educational department.

Yesterday he (my dad) received a printout of the Dutch wikipedia-page on the Brakwaterstrandschelp (Rangia Cuneata). On the page Paul (who sends his regards at the bottom of the document) traced around the scallops with a blue ballpoint pen.

My dad added in capitals – also with a blue ballpoint pen – that the Rangia Cuneata is an invasive species, native to the Gulf of Mexico. The first time it was observed in Europe was in Antwerp in August 2005, most probably they reached Europe in the ballast water tanks of large ships.

On a pile of fresh hospital sheets, near the radiator, the tangerine curtains and the black marble window sill (the window looks out over the parking lot), underneath the two-day-old bouquet of flowers and next to a pile of magazines with a handwritten note on top (about a syrup that relieves slime and tastes like oranges), lie two sheets of paper.

Earlier that day the physiotherapist had come by. Twice. Once in the morning and once in the afternoon. He had each time drawn the first line, as an example. A straight line in the morning, a curvy line in the afternoon.

With a ballpoint pen my grandfather, who is recovering from an accident, diligently copied the examples (31 in the morning, 5 in the afternoon).

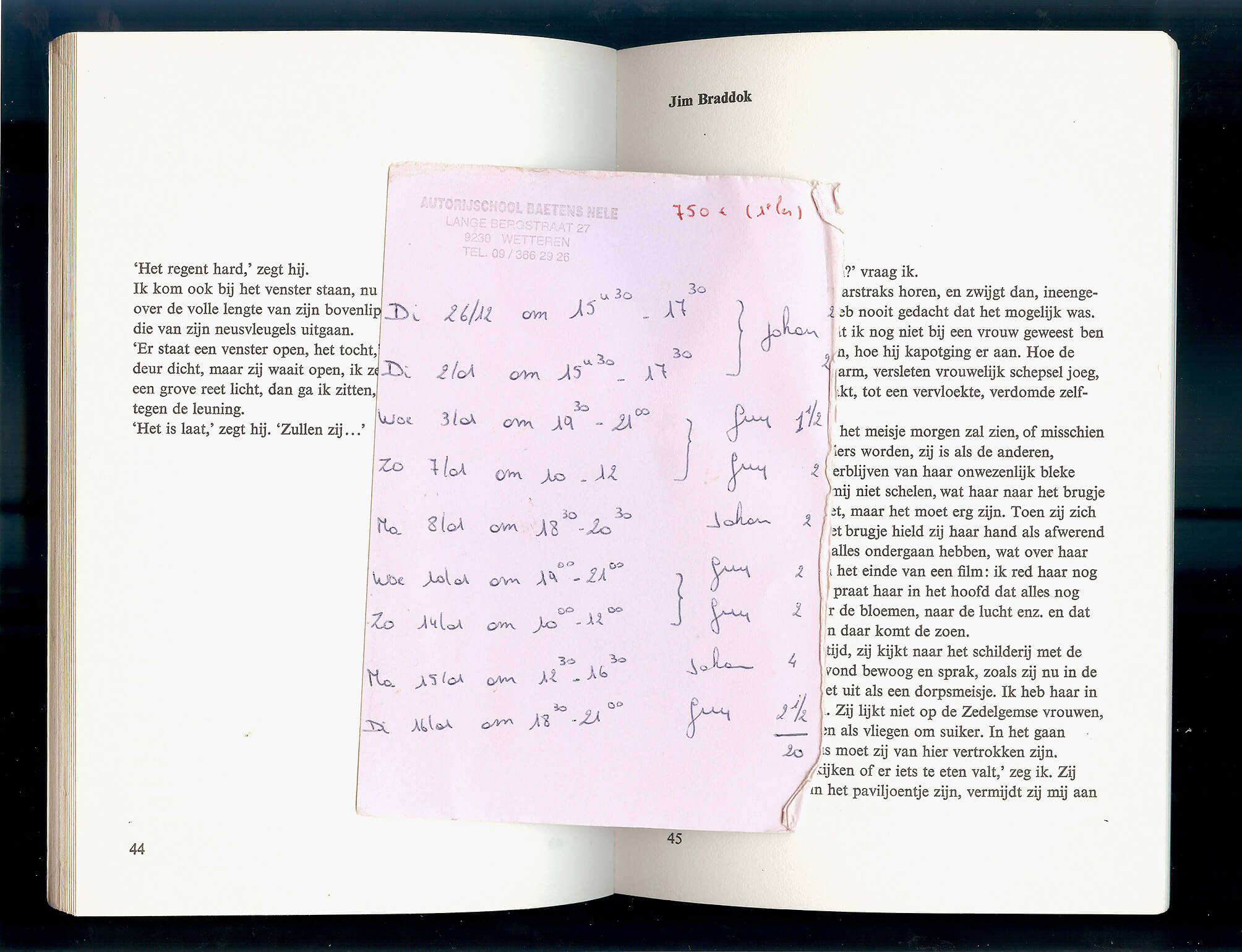

In his debut novel ‘De Metsiers’ Hugo Claus employs a multiple narrative perspective. In the copy I picked up in a thrift store, there’s a bookmarker between pages 44 and 45 where the perspective shifts from Ana to Jim Braddok. It’s pouring. The pink piece of paper lists 9 sessions at a driving school. There’s a total of 20 hours, taught alternately by Johan and Guy.

In 2000, 2006 and 2017 the twenty-sixth of December was a Tuesday. (Earlier years are improbable, since the Euro was not introduced yet.)

Claus, H. De Metsiers. Amsterdam: Uitgeverij De Bezige Bij, 1978.

‘ORIGINAL. Rire de tout ce qui est original, le haïr, le bafouer, et l’exterminer si l’on peut.’

[‘ORIGINAL. Laugh with everything that’s original, hate it, scold it, exterminate it if you can.’]

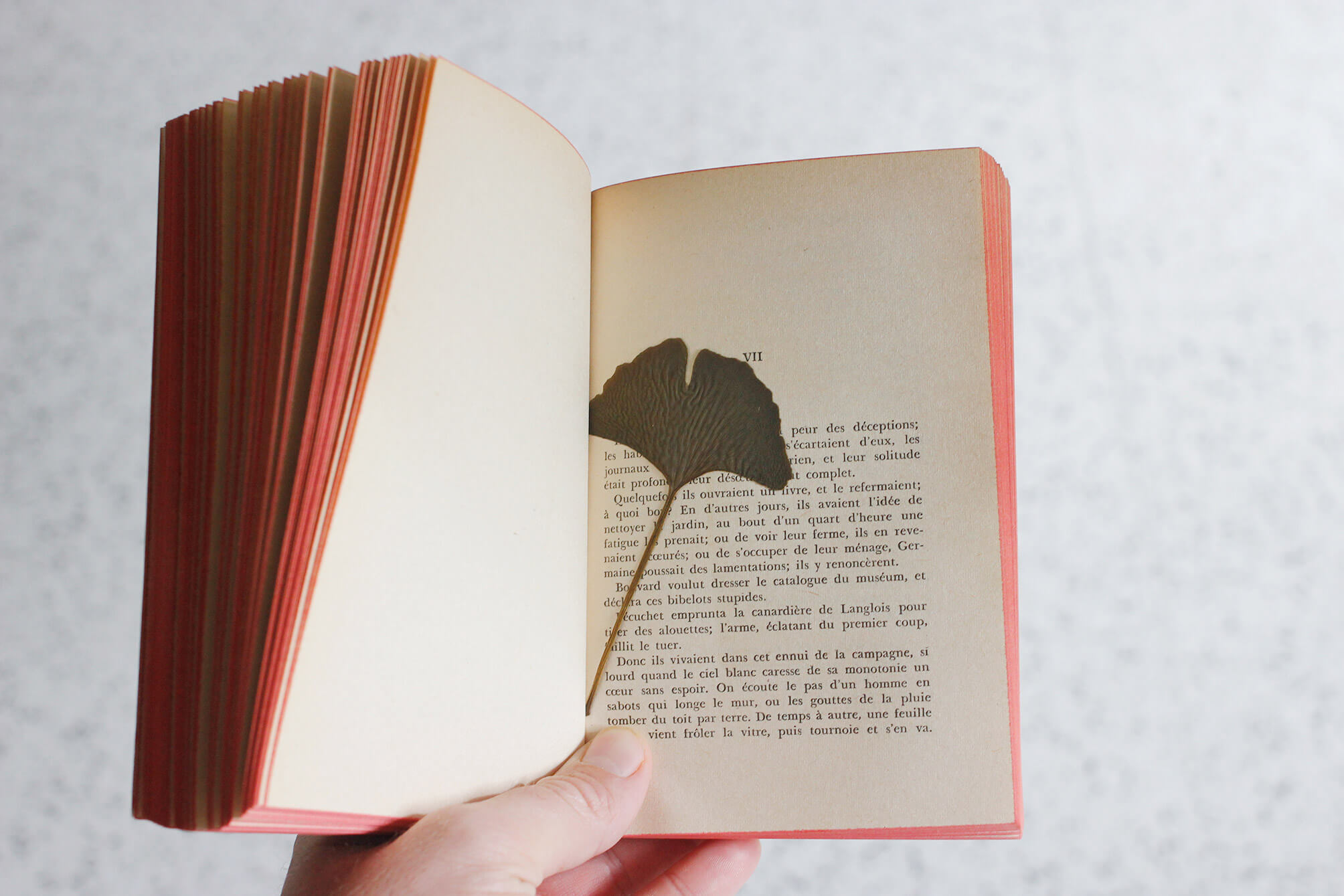

Flaubert. Bouvard et Pécuchet (présenté par Raymond Queneau). Paris: Livre de poche, 1959 (with p. 232-233: dried leaf of a ginkgo tree, and p. 324-325: dried leaf of a birch tree), p. 429 [2,00 EUR, Librairie Vic-sur-Cère, August 2021].

On Wednesday, May 9, 2018 at 2:23:14 PM Koh Elaine starts the thread original or original copy on the The Free Dictionary by Farlex’s forum.

‘Is “original copy” correct or should it be “original”? Thanks.’

The seventh reply to Elaine’s question is Wilmar’s on Thursday (his was preceded by towan52, georgew, NKM, Koh Elaine, Sarrriesfan, ChrisKC, Ashwin Joshi).

‘An original copy IS the original.

Folks usually call the document first created the original, but some will say original copy. If I run that original thru the copy machine, I end up with two copies (yes, I said copies) of the same thing – the original and the duplicate of it (in terms of content). This is how the term is commonly used.

If your writing or conversation depends heavily on understand the difference, I would recommend using the terms original and duplicates. There are many times when that is very important, in that the original must be retained by a particular party, and the duplicates are marked as such and distributed or stored as required depending on the document and the circumstance.

If you are just trying to make sure that you have enough copies to distribute to everyone at the company meeting this afternoon, use whatever terms trips your trigger. But, if you want to ensure that you keep custody of the original, so that you can make additional duplicates (copies) when additional people attend, then be more specific about the words you use.

OH, and, please, in the future, include some context with your question. Asking if “word” is correct doesn’t go very far in supplying a reasonably useful response.’

https://forum.thefreedictionary.com/postst182102_original-or-original-copy.aspx

Our one year old’s favourite toy he’s not supposed to play with is the HP Officejet Pro L7590 All-in-one in my office. I have given up on forbidding him to play with it. We have a new game: he brings me one of his other toys, we put it on the flatbed, close the lid – as far as possible –, press the button ‘START COPY – COLOR’ and wait for the print to come out of the machine. When we place the original onto the copy, he laughs. So far we have copied his blue pacifier, his planet-earth-bouncy-ball and his rattling crocodile.

When I grew up, my parents told me that the number of raisins in the local baker’s raisin bread attested to the result of the most recent soccer match of KAA Gent. A victory was celebrated by throwing more raisins into the dough than usual, a loaf following a painful loss was hardly a raisin bread at all.

The baker retired long ago. Today my two-year-old son picked out all the raisins from his slice of bread. KAA Gent’s last game was a tie against Union.

Most mornings I eat three slices of bread. I stack them. Between the highest slice and the one in the middle I put a slice of cheese (young Gouda). I put the whole in the microwave1 for 1 minute and 50 seconds. The result is what I like to call a smelteram2.

On the morning of my thirty-second birthday the plate broke in half during heating.

A contraction of smelten (Dutch for melting) and boterham (Dutch for a slice of bread).

It’s early spring. The pool is covered with a sheet of plastic. The deciduous trees are just leafing out. A tree stump serves as a placeholder for the diving board’s foot – it was customary to take it indoors for winter – and keeps people from kicking its threaded rods sticking up from the silex tiles that line the pool.

The upper right corner of the plastic frame is missing. It’s probably where the insect – now dead, dry and yellowish – got in. The frame was left behind in the laundry room overlooking the garden, the pool and the pool house. At the time it hadn’t been used for quite a while. Half empty, the water green.

In summer, when the wind dropped, horse-flies came. You could shake them off temporarily by swimming a few meters underwater.

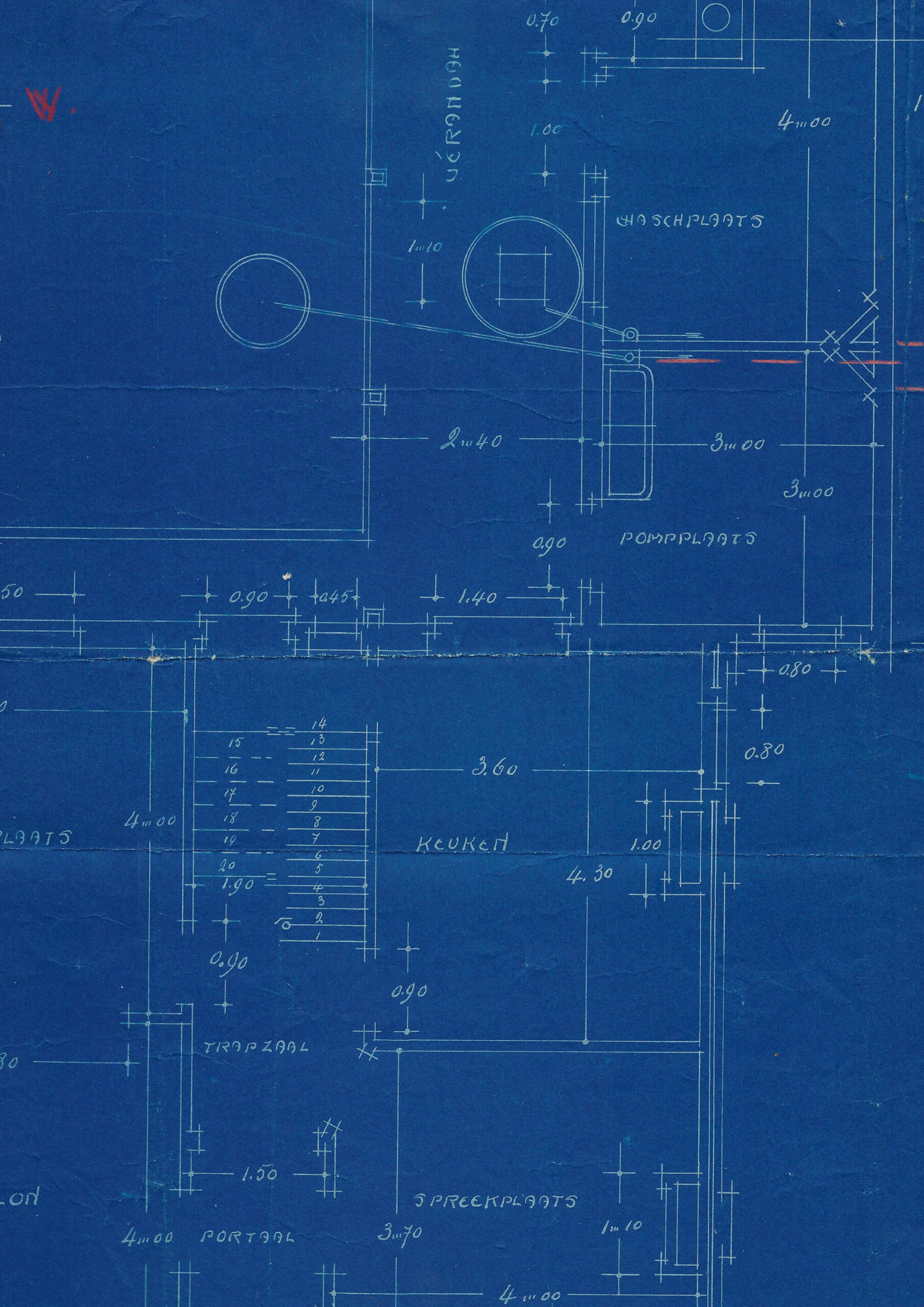

In the archive of the architect O. Clemminck, there is a piece of a plan of a building in a suburb in Gent. It presents the ground floor. There is a kitchen, a salon, an eating place, a meeting place. The missing part would have stated the exact address, the name, and maybe the profession of the owners. The plan of the first floor might have given an indication of the number of (anticipated) family members, based on the number and size of sleeping rooms.

At the southern edge of (the plan of) the lot, O. Clemminck has drawn a laundry room that gives out to a vérandah. The spelling of the Dutch word – nowadays written as veranda – is remarkable, as is its etymology, which is unclear and a matter of debate among scholars. The word might have Portuguese (varanda: railing) and Catalan roots (baranda: barrier), maybe also origins in the Lithuanian Žemaitan dialect (varanda: loop plaited from flexible wings) and might also be traced back to a Sanskrit root (varandaka: rampart separating two fighting elephants).

The vérandah O. Clemminck proposes is 2,40 meters by, at least, 2,80 meters.

K. says that the stall where he usually buys fruit has already been packed up. But he is not worried about the quality of the fruit the other vendor sells. He gestures encouragingly.

Five signs of type-1, eleven of type-2 and two of type-3 are visible. Four of type-2 (two visible, two deduced) and two of type-3 retain two vehicles.

Márk Redele pursues projects that fundamentally relate to architecture and its practice but rarely look like architecture. www.markredele.com

Until recently, for as long as I could remember, the packaging of Tabasco® Pepper Sauce had been unchanged. On the front of the packaging, there is a photograph of a bottle of Tabasco®, scale 1:1, against an orange background.As far as packaged goods go, this is a highly idiosyncratic and quirky example.

The background colour approximates the colour of the liquid inside the bottle, resulting in as good as no contrast. Moreover, as the image of the bottle is scale 1:1, the packaging becomes kind of unnecessary and superfluous, also because the life-sized image of the bottle is the only way information is given to the customer: there are no additional slogans, no repetition of the brand name, no props and no decor. The image of the bottle advertises the bottle. It seems to add nothing the bottle could not do by its own (like a bottle of wine does).

What makes the packaging truly stand out, however, is the fact that the image of the bottle is not positioned vertically, but is slightly askew. It seems to be the result of a design error, and has an amateur feel to it. The decision to keep it as such and not correct it up until today, is, however, a stroke of genius. The non-vertical positioning alters the relation of the image of the bottle to the bottle inside: as the box is standing on a shelf, the tilted image of the bottle undermines its representational superfluousness.

It must have been four or five years ago, that I noticed the change in Tabasco’s® up until then stable, unchanged and thus kind of unfashionable presence in supermarkets (vinegar section). On one of the box’s sides, there had always been a photograph of a man, clipboard in hand, looking upwards to a huge wooden barrel full of Tabasco®. He was inspecting something, from the outside, writing it down.

A couple of years ago, the man disappeared from the packaging. I think he was replaced by a pizza (as one of the suggestions for using Tabasco® on, besides on hashed meat (with an egg yolk, fries and lettuce) and spaghetti bolognese) or a black-and-white image of a part of an oak barrel. It is unclear who is inspecting the barrels now.

French writer Raymond Queneau did extensive research into what he called hétéroclites, and at other times fous littéraires, a continuation of a longstanding bibliographic project of assembling texts proposing eccentric theories that were never picked up by the scientific community. Disappointed by the results of his research and unable to find a publisher, he abandoned the idea of publishing the encyclopaedia he was compiling. Later, in his encyclopaedic novel Les enfants du limon, he picks up the thread, from a different perspective. It tells the story of two quirky characters, Chambernac and Purpulan, wanting to compile an encyclopedia on fous littéraires. The novel cites from the texts they have dug up. The novel ends when they give up on the project, and give their findings to a novelist they meet and who says to be interested in the material, and asks if it would be OK if he’d attribute it to a character in a story he’s writing. Chambernac agrees, asking the name of the novelist he’s meeting: ‘Monsieur comment?’ – ‘Queneau’.

Queneau, R. Aux confins des ténèbres. Les fous littéraires du XIXe siècle (M. Velguth, red.). Paris: Gallimard, 2002.

Queneau, R. Les enfants du limon. Paris: Gallimard, 2004 [1938].

Interior of Eben-Ezer: photocopies and replicas of among other things an Edit du Roy and a photograph of a Marche pour la liberté de conscience, 1956. Handwritten labels are added beneath the blue frames. Due to limited lighting, and an interdiction to use the camera’s flash, some labels are illegible, even when zooming in on the picture. It is unclear what the bottom left replica of a painting is (it has a Brueghelian air to it) and the upper right replica of a photograph.

The walls are made of flint, harvested from quarries in the neighbourhood.

A cigar box, standing at the back of a shelf next to the heating installation, with in it silex-like stones with what seem to be traces of prehistoric usage.

In the garage, there were papers (the archive of O. Clemminck) and objects (stones, tiles) left to us by a man who had worked at the city archive. He was an acclaimed expert on our village’s history.1

A recent study by professor Philippe Crombé at Ghent University states that during the last Ice Age, in the region where I grew up, there was once a great lake, with, at the shores, proven presence of prehistoric man. As a kid, we dug up shells with a toothbrush, and set a perimeter with plastic tape. The former presence of a tavern where my parents now live, and the restaurant which still serves seafood at the other side of the road, prevented accurate dating.

On January 23, 2020 a young couple walks around the drained reservoir of Kruth-Wildenstein.

It’s freezing. They’re expecting their first child within a month.

During the one day course Safety and Avalanches, teacher G.T. shows pictures of different manifestations of snow and ice. If one learns to read them, one can deduce the wind direction when hiking or skiing in mountainous terrain. Wind direction is crucial for assessing the stability of the snow. G.T.’s examples are of Austrian origin. He speaks about ‘Anraum’: displaced snow can get stacked horizontally against an object, such as a tree or a cross. The snow ‘grows and builds into the wind’. Counter-intuitively, the snow points to the side the wind is coming from. One can expect dangerous terrain in the direction of the ‘unbuilt’ side of the object.