What constitutes a ‘document’ and how does it function?

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the etymological origin is the Latin ‘documentum’, meaning ‘lesson, proof, instance, specimen’. As a verb, it is ‘to prove or support (something) by documentary evidence’, and ‘to provide with documents’. The online version of the OED includes a draft addition, whereby a document (as a noun) is ‘a collection of data in digital form that is considered a single item and typically has a unique filename by which it can be stored, retrieved, or transmitted (as a file, a spreadsheet, or a graphic)’. The current use of the noun ‘document’ is defined as ‘something written, inscribed, etc., which furnishes evidence or information upon any subject, as a manuscript, title-deed, tomb-stone, coin, picture, etc.’ (emphasis added).

Both ‘something’ and that first ‘etc.’ leave ample room for discussion. A document doubts whether it functions as something unique, or as something reproducible. A passport is a document, but a flyer equally so. Moreover, there is a circular reasoning: to document is ‘to provide with documents’. Defining (the functioning of) a document most likely involves ideas of communication, information, evidence, inscriptions, and implies notions of objectivity and neutrality – but the document is neither reducible to one of them, nor is it equal to their sum. It is hard to pinpoint it, as it disperses into and is affected by other fields: it is intrinsically tied to the history of media and to important currents in literature, photography and art; it is linked to epistemic and power structures. However ubiquitous it is, as an often tangible thing in our environment, and as a concept, a document deranges.

the-documents.org continuously gathers documents and provides them with a short textual description, explanation,

or digression, written by multiple authors. In Paper Knowledge, Lisa Gitelman paraphrases ‘documentalist’ Suzanne Briet, stating that ‘an antelope running wild would not be a document, but an antelope taken into a zoo would be one, presumably because it would then be framed – or reframed – as an example, specimen, or instance’. The gathered files are all documents – if they weren’t before publication, they now are. That is what the-documents.org, irreversibly, does. It is a zoo turning an antelope into an ‘antelope’.

As you made your way through the collection,

the-documents.org tracked the entries you viewed.

It documented your path through the website.

As such, the time spent on the-documents.org turned

into this – a new document.

This document was compiled by ____ on 08.12.2023 16:05, printed on ____ and contains 21 documents on _ pages.

(https://the-documents.org/log/08-12-2023-5504/)

the-documents.org is a project created and edited by De Cleene De Cleene; design & development by atelier Haegeman Temmerman.

the-documents.org has been online since 23.05.2021.

- De Cleene De Cleene is Michiel De Cleene and Arnout De Cleene. Together they form a research group that focusses on novel ways of approaching the everyday, by artistic means and from a cultural and critical perspective.

www.decleenedecleene.be / info@decleenedecleene.be - This project was made possible with the support of the Flemish Government and KASK & Conservatorium, the school of arts of HOGENT and Howest. It is part of the research project Documenting Objects, financed by the HOGENT Arts Research Fund.

- Briet, S. Qu’est-ce que la documentation? Paris: Edit, 1951.

- Gitelman, L. Paper Knowledge. Toward a Media History of Documents.

Durham/ London: Duke University Press, 2014. - Oxford English Dictionary Online. Accessed on 13.05.2021.

A malfunctioning of the camera leading to a double-exposed negative. The car is decisive in establishing the relationship between the superimposed photographs. In the middle of the image, we see it parked in front of the house. Slightly less visible is the same car, repeated but further away. This makes it possible to deduce that the dark outline of the house, with the roof and the chimney, is also the same house as in the other photograph. This time, the house is photographed relatively frontally (the slightly angled point of view allows to bring the shed at the back of the house in the line of sight), and from nearby. At the bottom left, the lines that make up the street help to see the continuity of the one photograph, while the electric wires at the top right aid to comprehend the other one.

The camera malfunction speculates on a future addition to the plot. The dark, outlined shed’s scale is realistic with regards to the scale of the house and itself (the shed) in the other photograph. Its position with regards to the other buildings seems logical. It imposes itself as a possible second shed for the owner to build in the next few years. In that future shed, the car, now standing in front of the house, could be comfortably parked.

The scientific exactitude sought for in the Iconographie de la Salpêtrière and the Nouvelle Iconographie de la Salpêtrière, the (in)famous scientific publications stemming from Paris’ psychiatric hospital La Salpêtrière (1876-1918), lead to an abundance of photographic images in their pages. The photographs’ ideal: ‘Trace incontestable, incontestablement fidèle, durable, transmissible’.1 The ambition of exactitude results in cold, and often cruel depictions of patients. In the digitized version of the Sorbonne library’s copies, some photographs have left an imprint on the opposite page. The knee of Charles, ‘le géant’, adds an unwanted layer upon its measures on the opposite page, while the photograph of the knee itself loses ink.2

Didi-Huberman, G. Invention de l’hystérie. Paris: Macula, 2014, 72.

Launois, P.-E., Roy, P., ‘Gigantisme et infantilisme’, Nouvelle Iconographie de la Salpêtrière, Tome XV, 1902, 548, pl. LXVI, online: https://patrimoine.sorbonne-universite.fr/fonds/item/2613-nouvelle-iconographie-de-la-salpetriere-tome-15?offset=6

It has been snowing. A black BMW is parked on the other side of the street and is cut in half by the separation between negatives 4 and 5. Apart from a slight kink in the landscape, the negative on the right is a perfect continuation of the one on the left. The fence around the orchard, the branches of the apple tree and the power lines connect implicitly in the void between the negatives.

Based on De Cleene De Cleene, The Situation as it Is. A Photonovel in Three Movements (APE, 2022).

The architect’s photographic archive contains seven images that can be labelled as panoramic pictures. However, they only appear as such when the photographs are viewed in the archive, as strips of negatives. In order to see the panoramic construct, the viewer needs to be presented with two consecutive negatives.

There are two kinds of panorama in the archive: the kind that can only be attributed to a kind of laziness or a need for efficiency on behalf of the architect, and another that originates from frugality.

The former type of panorama is created when the architect is documenting the situation as it is: it is compulsory to document the context of the building or lot, as part of a building application. He simply pivots from left to right, capturing the first and second photograph consecutively. On the filmstrip a panorama appears.

The other kind of panoramic picture only appears at the end of the film role. The last negative on the film has been exposed (the twenty-fourth or thirty-sixth), after which he exerts force onto the lever to move the film forward anyway. Some films are known to have, by accident, a twenty-fifth or a thirty-seventh negative. The plastic between the sprocket holes tears and the film does not advance enough. The result differs fundamentally from the other kind of panorama: there is no separation, no void between the negatives. Rather, there is a slight overlap. A thin, vertical strip of film that has been exposed twice, suggesting contiguity that might not be there. The two exposures might be from altogether different sites, creating a new situation.

Based on De Cleene, M. & De Cleene, A. The Situation as it Is. A Photonovel in Three Movements. Gent: APE, 2022

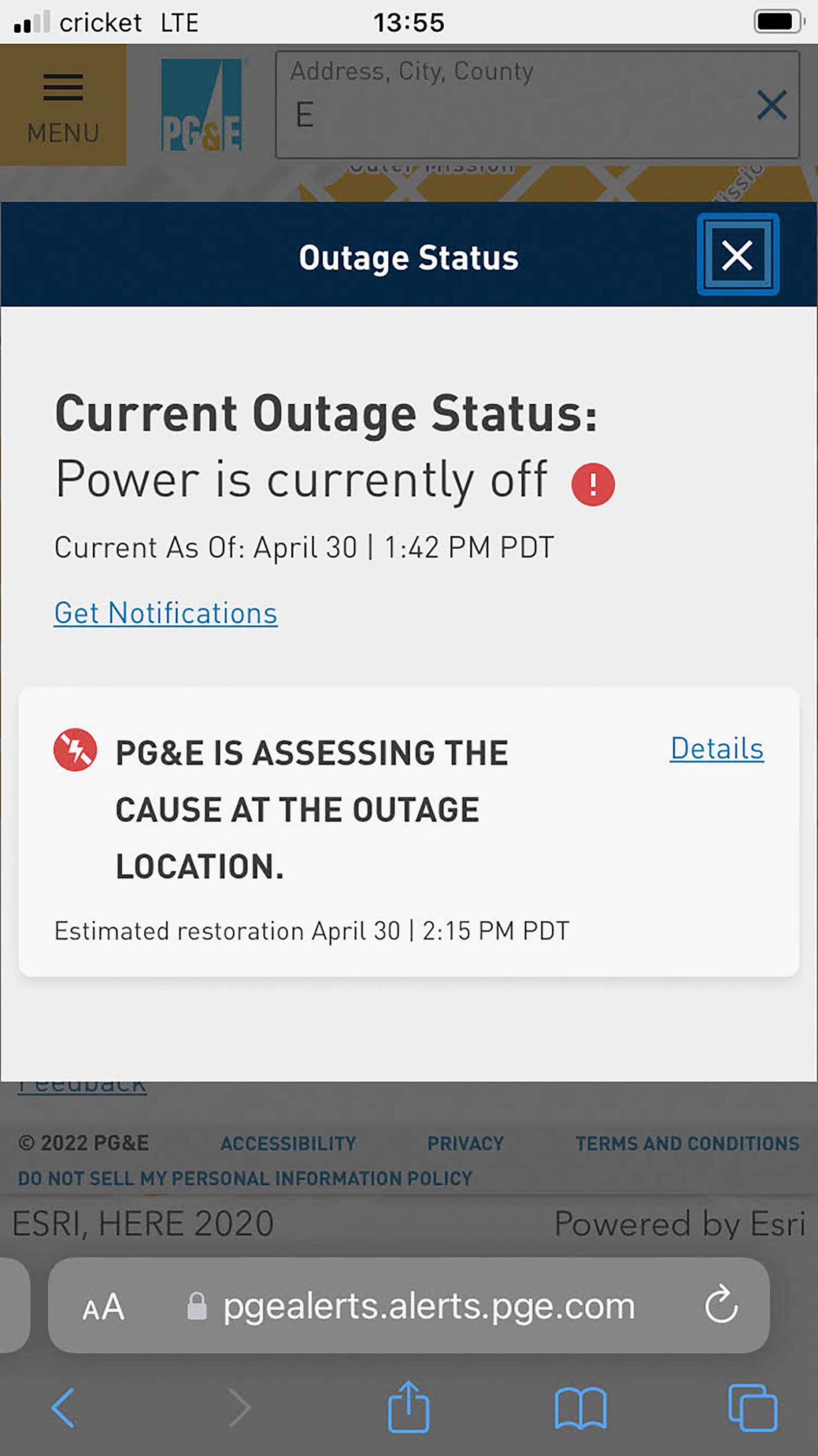

On a windy morning in April, I was on a video call with a friend, curator Maziar Afrassiabi. He listened patiently from Rotterdam as I labored over a direction for my research. It concerned a device I installed in his art space, Rib, six months prior, that monitored blackouts across California by scraping real-time data from utility companies. When a county experienced a significant blackout, it would cut Rib’s electricity in kind—causing Rib to inherit and adapt to conditions that shape Californian infrastructure. During its operation, I’d been researching the grid—learning what it is, why it fails, and how communities respond when it does.

We took a short break. Maziar, with tired eyes, stepped away for a smoke. While waiting, I watched the power lines outside my window sway limply in the breeze. In spite of its apparent lifelessness, I’ve always thought of electricity as a psychological force. My mind wandered through a cursory model of the grid, idiosyncratically cloudy and detailed.

Energy simultaneously generated and used, cascading infrastructural operations in a blink. Outlying stations burning, vaporizing, absorbing fuel, spinning vast electromagnetic turbines. Oscillating current. Neighboring transformers boosting volts to kilovolts, compensating for lost energy coursing through long-distance transmission supported by pylons peppered across Menlo Park.

Current flows into enclosed substations. Transformers, insulators, resembling a kind of industrial Watts Towers—though uninhabitable and anonymous by comparison—step voltages back down to levels safe enough for wires traversing the city. They branch out through streets via buried cables or, like the lines outside my window, are strung atop Douglas fir utility poles at roughly 30-meter intervals…curious vestigial markers. I’d read somewhere they were provisionally pitched when Samuel Morse found that telegraph signals wouldn’t transmit through the earth.

Each pole divides vertically into distinct zones, spaced apart for safety. Treacherous high-voltage wires from substations pass along the top, while safer signals—cable internet and landlines—hang nearest to the ground. The high-voltage wires enter through a barrel-shaped pole-mounted transformer. Within, submerged in oil, two tightly wound copper coils magnetically harmonize, delivering 240 and 120 volts to three exiting wires, each connected to the electrical meter attached to the building…

A blackout in my neighborhood cut my thoughts and the meeting short. The sudden silence in my apartment indicated Maziar was also in the dark. I received a text message from him and the utility company.

Mathew Kneebone is an artist based in San Francisco. His interdisciplinary practices takes different forms, all in relation to an interest in electricity and technology. He teaches studio and thesis writing at California College of the Arts.

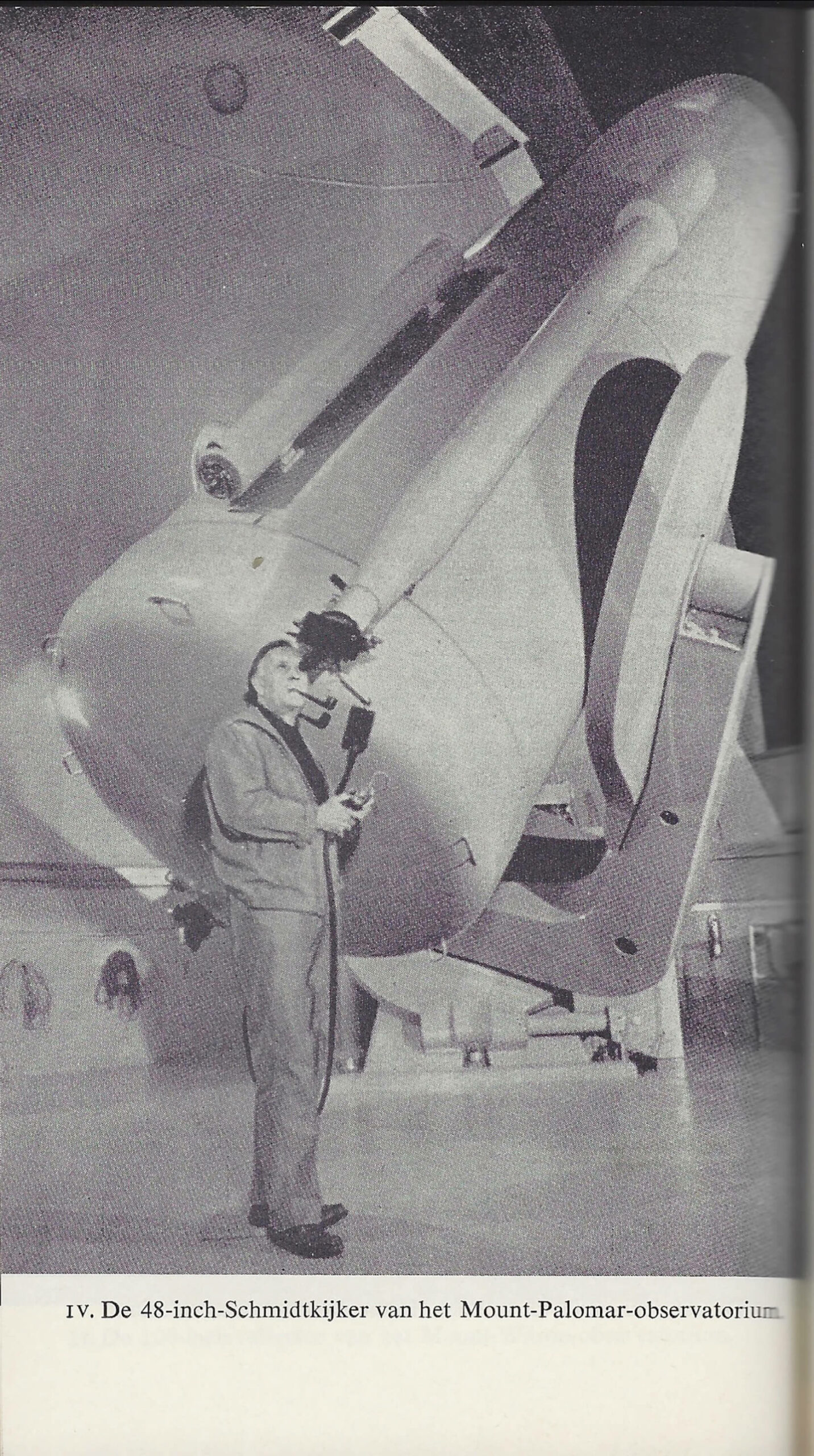

The 48-inch Oschin Schmidt, a renowned reflecting telescope at Palomar Observatory, California, was used for the Palomar Observatory Sky Survey (POSS), published in 1958, one of the largest photographic surveys of the night sky.

Based on the man’s pipe shadow’s direction, thrown onto the telescope, there is reason to believe an off-camera flash was used to make the picture.

Holding two cans of spray paint, a city employee walks through a sweet chestnut grove on the graveyard. He’s looking for potholes.

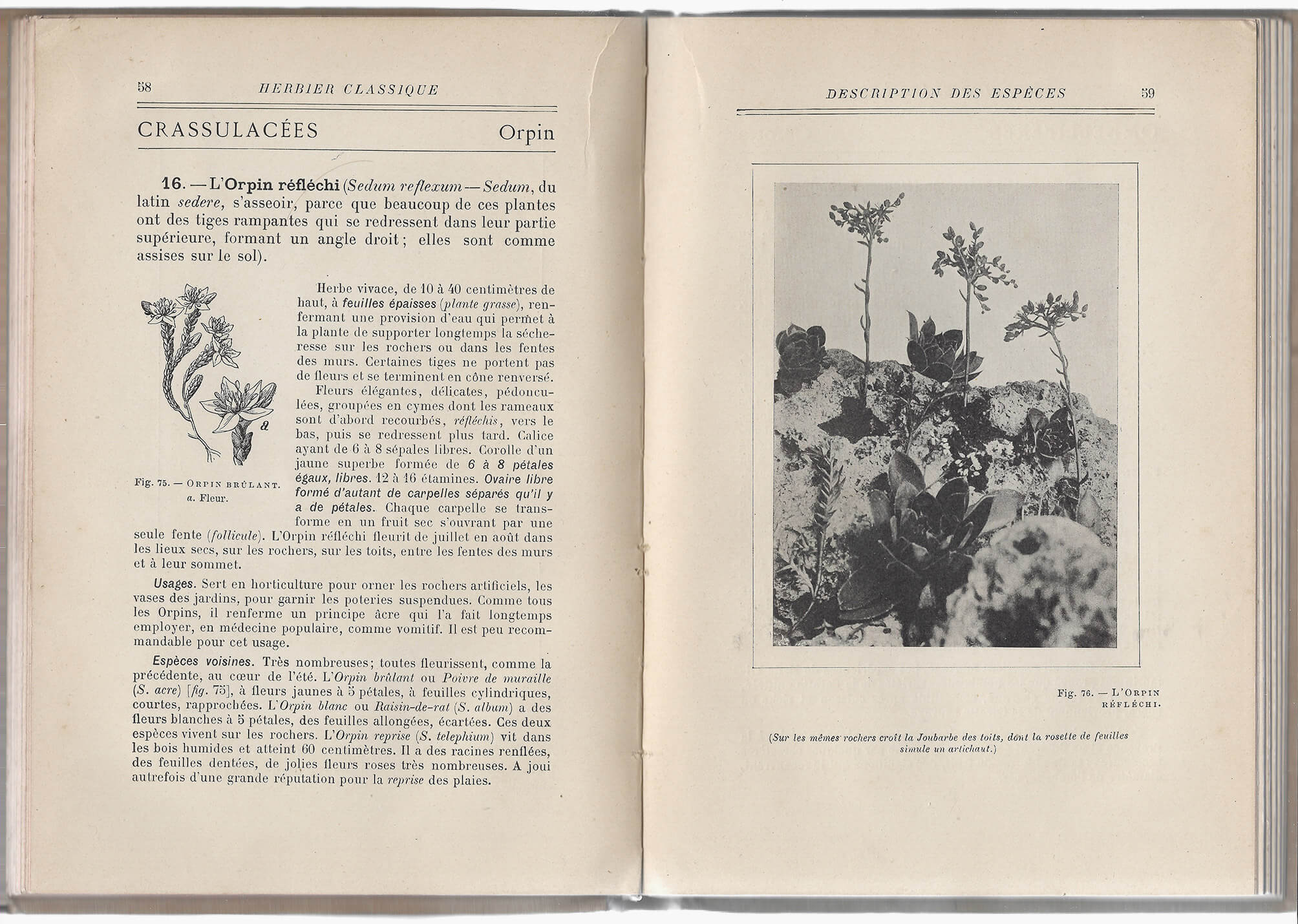

The Sedum reflexum grows on rocky soils and in crevices of walls. In L’herbier classique, it is depicted in two ways, just like the other plants in the book. This double portraiture is important, the author states in the introduction: ‘one consists of the reproductions of the photographs taken by the author of this book […]; the other, drawings made by excellent artists who observed the plants themselves, showing details photography can’t reproduce, highlighting aspects the photographs leave untouched. […] From this double representation, interesting comparisons can be made, highly enlightening from an artistic point of view, between the realistic aspect of nature’s “productions” and the interpretation thereof by the draftsman’ (5).

A detail not covered by the drawing of the sedum reflexum, is the presence of other species in the vicinity of the plant, a detail shown in the photograph and described in the caption: ‘The Common houseleek grows on the same rocks, with its rosette of leaves pretending to be an artichoke’ (59).

Five white boulders close off a shortcut for motorists who attempt to cut the bend in the road. The southernmost roof’s pitch runs opposite to the landscape’s slope. The lower roofline is, therefore, only about one meter above a small, triangular patch of grass which is hidden from view by a hedge. In summer, when the roofing gets hot and soft, text and drawings get pressed or carved into it.

Google Earth

A carving that looks like a stitched-up scar (a long, slightly curved line crossed at a right angle by eleven short straight lines) is inserted into a short statement about Celine and Logan. An initial of Celine’s last name is included. At first sight it looks like a ‘D’, but the line through the middle might just as well make it a ‘B’. Maybe it was Celine D who added the line in an attempt to convince those reading the roofing that it’s actually Celine B who blows Logan.

In summer, the roofing gets hot and soft. In winter, it gets cold, hard and brittle. None of the gates to the garages are open. It’s unsure whether the numerous texts and drawings – some dig deeper than others – have caused leakages.

A square photograph with an Arabic and French text underneath it is mounted on a foam board, in turn mounted on a sheet of plexiglass. The picture in the middle is flanked by a photograph of and a text about the tumuli of Umm Jidr (left) and the excavations at Abou Saybi (right). They are mounted on the West wall of Guest Room 3 at the Qual’at Al-Bahrain Site Museum, Seef, Bahrain.

Necropolises make up the main archaeological testimonies of the Tylos period (4th century BC – 3rd century AD). The urn in the photograph contains the remains of several babies. They most likely fell victim to an epidemic. The size of the ruler next to the urn remains unspecified.

The photograph of Room 3 was made while in mandatory self-isolation after flying to Bahrain from Frankfurt and waiting for the result of a Covid-19 test.

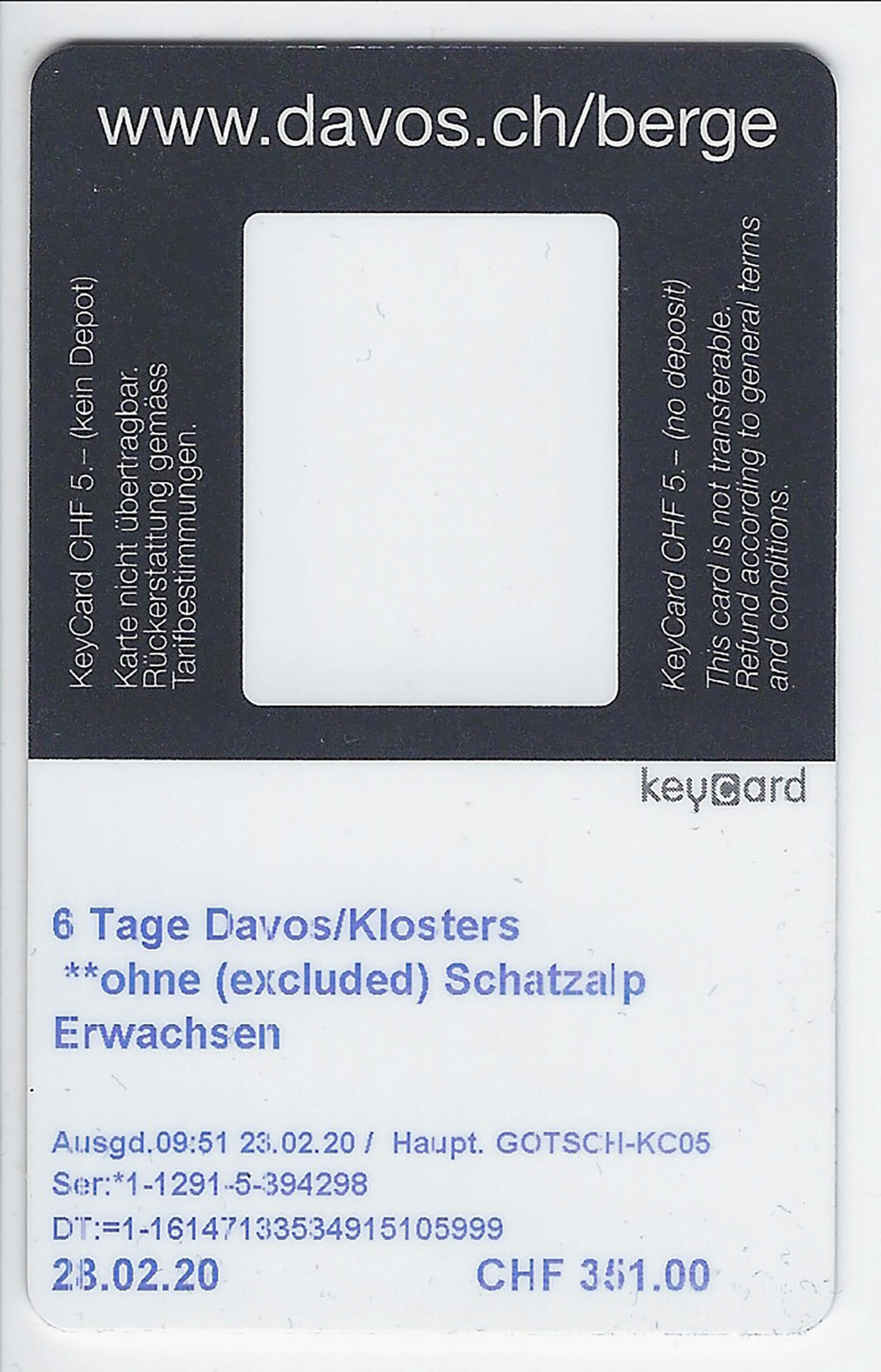

A skiing holiday with my in-laws. The ski pass does not allow you to visit Schatzalp. We buy a separate ticket and take the train up the hill to the hotel, which served as the backdrop for Thomas Mann’s Magic Mountain. The stately hotel and former sanatorium is gorgeous.

Meanwhile, a new virus is spreading. Some people are coughing. I am keeping distance while waiting in line to take the train back down to the snow-covered village.

A square photograph with an Arabic and French text underneath it is mounted on a foam board, in turn mounted on a sheet of plexiglass. The picture in the middle is flanked by a photograph of and a text about the tumuli of Umm Jidr (left) and the excavations at Abou Saybi (right). They are mounted on the West wall of Guest Room 3 at the Qual’at Al-Bahrain Site Museum, Seef, Bahrain.

Necropolises make up the main archaeological testimonies of the Tylos period (4th century BC – 3rd century AD). The urn in the photograph contains the remains of several babies. They most likely fell victim to an epidemic. The size of the ruler next to the urn remains unspecified.

The photograph of Room 3 was made while in mandatory self-isolation after flying to Bahrain from Frankfurt and waiting for the result of a Covid-19 test.

Besides the scale indicating the length in centimeters, and the marks made by using it, a folding ruler displays other marks. These are the marks found on the weber broutin www.weber-broutin.be folding ruler, from left to right:

- 2m (in a frame, between 1cm and 2cm); indicating the total length of the folding ruler.

- a hexagon, barely visible, punched into the wood (between 2cm and 3cm); unknown signification.

- LUXMA (in a frame, between 4cm and 5cm); the manufacturer of the folding ruler (different from the company who ordered the folding ruler, their (the company’s, i.c. weber-broutin’s) name is printed on the sides of the ruler, and is only readable when the ruler is folded together for at least 50% (=1m).

- III (in an oval, between 6cm and 7cm); indication of the preciseness of the scale in centimeters, with ‘I’ in roman numbers meaning the most precise, and ‘IV’ in roman numbers meaning the least precise. (It is therefore not entirely certain that the ‘III’ on weber-broutin’s folding ruler can actually be found between 6cm and 7cm.)

- D 99 (in an oval, probably between 7cm and 8cm, see argument mentioned above); unknown signification.

- 1.1.60 (in an oval, probably between 7cm and 8cm, beneath D 99), signification unknown.

Belgium, approximately 1.5km from the French border, photograph made on 16.06.2018.

The European flag symbolises both the European Union and, more broadly, the identity and unity of Europe. It features a circle of 12 gold stars on a blue background. They stand for the ideals of unity, solidarity and harmony among the peoples of Europe. The number of stars has nothing to do with the number of member countries, though the circle is a symbol of unity.1

- Coat of arms of Gmina Puck, a rural district in Puck County, Pomeranian Voivodeship, in northern Poland.

- Illegible.

- F.C. Hansa, Mecklenburg, Pommern, FC Hansa Rostock is a German association football club based in the city of Rostock, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern. They have emerged as one of the most successful clubs from the former East Germany and have made several appearances in the top-flight Bundesliga. Hansa Rostock’s official anthem is “FC Hansa, wir lieben Dich total”. Hansa struggles with hooliganism, estimating up to 500 supporters to be leaning towards violence. The club’s logo consists of a red sailing ship with a blue sail showing the Rostock Griffin.

- Mon École Écologique.org is an organization for environmental conservation. On 07.01.2021 there was no website listed on this URL.

- Illegible.

- Illegible, apart from ’1962’ in the middle.

- Innocenti Bruderschaft, EL, 2018, a community of German Lambretta Innocenti riders and aficionados.

- Imag’Ink, Bretignolles Sur Mer, Tatoueur, 06 06 44 13 51, a French tattoo shop.

- Illegible.

- Hardly legible, the only word that can be made out is ‘Futbolom’: Russian for soccer.

- Kaluga on tour. Kaluga is a Russian city 150km southwest of Moscow. It is often called the cradle of space exploration thanks to the city’s most famous resident: Konstantin Tsiolkovsky.

- Hansa Ultras, F.C. Hansa. The Ultras are a group of F.C. Hansa fans (see: ‘3’).

- Illegible because ‘12’ was stuck over it.

- Illegible.

- La Hutoise is a regional student-association for higher education students from the Belgian town of Huy and its surroundings. Its aim is to bring together students from Huy in a spirit of camaraderie and to perpetuate student folklore. The logo consists of a two headed bird of prey with a cap on each head. The bird wears a scarf over one shoulder and holds a glass of beer in each paw.

- F.C. Hansa, Grimmen. The F.C. Hansa logo (see ‘3’ and ‘12’) is combined with the coat of arms of Grimmen: a griffin on a pile of 10 bricks. Grimmen is a German town in Nordvorpommern on the banks of the river Trebel.

- Illegible.

- Heil Hansa. To the left of this text the F.C. Hansa logo (see ‘3’, ‘12’ and ‘16’), on the right a logo consisting of a black bull with his tongue out and a golden crown on his head. This controversial sticker lead to several arrests in the run-up to the match between F.C. Hansa Rostock and Bayern München in February 2020. Supporters of F.C. Hansa had attached this sticker to public buildings on their way to the stadium.

- Illegible because ‘16’ was stuck over it.

- The Cuban flag.

- Illegible.

- Illegible.

- Kaluga (see ‘11’).

- De Veterinnen, a round, black sticker with a red print of a head wearing a round hat and a carnivalesque collar with a carrot for a nose. No further information found.

- Zlombol 11. Złombol is a yearly charity car rally racing event that starts in Katowice Poland. Contesters must drive a car that was built or designed during the communist era. The destination of the 2011 edition was Loch Ness.

- F.C. Hansa, Mecklenburg, Pommern, identical sticker to ‘3’, see also ‘12’, ‘16’, and ‘18’.

- Torpedo Moscow, only for white. Football club Torpedo Moscow is a Russian professional club based in Moscow, founded in 1930. Some fans of the club wave far-right symbols and banners, both during and outside of matches. Massive fan-protest ensued when the club tried to sign a black player in 2018. The player’s contract was cancelled.

- Heil Hansa. See ‘3’, ‘12’, ‘16’, ‘18’ and ‘26’.

- Illegible.

- Illegible.

- Illegible.

- Illegible.

- F.C. Hansa. Variation of ‘3’ and ‘26’ with a circle of yellow crops around the logo. See also ‘12’, ‘16’, ‘18’ and ‘28’.

- Live animals, contents: Rivne UA. These stickers are required by the International Air Transport Association for airline cargo pet travel. Rivne is a city in western Ukraine (UA) with an international airport. The sticker does not specify the transported animal but displays a dog, two birds, two fish and a turtle.

- Illegible.

- Illegible.

- Illegible.

- Illegible, apart from ‘lska’ on the bottom.

- Norrland Fly Guys, Reading Water. The sticker displays a minimal landscape with two pine trees, and a shed on a chunk of floating ice, a single four-point star shines in the sky. Norrland is the northernmost part of Sweden. No further information found. Whether the ‘fly guys’ own airplanes or are involved in fly fishing is unclear.

- This sticker displays – what appears to be – a smiling potato in front of an enlarged snow crystal. No further information found.

- Traumsucht is an artist collective from Berlin. Their website lists German rap-artists

- Illegible.

https://europa.eu/european-union/about-eu/symbols/flag_en

The GPS-plotter displays the ship near Keyhaven Lake, indefinitely. The sea appears calm, the horizon is level from one perspective.

In his Handboek Varende Scheepsmodellen (Handbook Sailing Ship Models) André Veenstra explains the different classes in ship model-competitions. There’s a wide variety. For static ship models the most important one is ‘truth-to-nature’. A jury compares the model to photographs of the actual ship and brings into account categories such as amount of work, degree of difficulty, scale ratio, construction execution and painting.

The most interesting class – according to Veenstra – is F 6. In this particular class, a number of participants with different boats will form a team. Together, they will perform a certain ‘act’ with a maximum duration of ten minutes. During the act, they mimic a slice of reality. Such as, for example, ‘rescuing’ and towing a ship in distress; extinguishing a fire on a tanker or oil rig, lichen and/or tow the sunken wreckage to the harbor, stage a naval battle, etc.

Page 262 shows a photograph of such a mimicked slice of reality. The caption explains: ‘Image 14.15. The Dutch demonstration in the F 6 class during the European Championship of 1975: the oil rig is set on fire by a motorboat with terrorists. The fire is extinguished and the oil rig is quickly towed to a safe harbor by tugs. The show was performed by six people and took a very creditable fourth place.’

On Mondays, before noon, I go to the supermarket with my two-year-old son. After passing the lasagnes, the loaves of bread and the fruit and vegetables, we make a short stop at the aquarium with the lobsters. Around New Year, there are two of them.

After we’ve paid for the groceries and have put them in the car, we walk into the pet shop. We look at the parrots (Jacques, Louis and Marie-José), the rabbits, the guinea pigs, the assorted caged birds and the fish and turtles. He’s very fond of the Cyphotilapia Frontosa Burundi. He calls them zebras. They hail from Lake Tanganyika, the label says. It’s the second-oldest freshwater lake, the second-largest by volume and the second-deepest. The pet shop has adorned their aquarium with a scene of ocean waste.

In an effort to avert guilt, I look for something cheap and more or less useful to buy: birdseed, a snack for the neighbour’s cat, a comb for his grandparent’s Labrador, etc.

_44A6588.dng

At 13:26:43 I took a photograph of a concrete building without windows in an industrial zone just south of Brussels.

_44A6590.dng

At 16:46:15 I photographed a succession of office buildings in the same industrial zone.

_44A6589.dng

I must have walked about 1 kilometer between the concrete building without windows and the section of the industrial zone with the offices. At 13:43:49, the camera, safely stored in my backpack, recorded 0.4 seconds of the 20 minutes it took me to get there.

In The Snows of Venice, Alexander Kluge wonders whether he can take the liberty to conjure up what the sky looked like on 31 December 1799, as Schiller made his way to Goethe’s house. He goes on by saying that, historically, there’s a ‘LACK OF SENSORY ATTENTION AT CRUCIAL MOMENTS’.1 There are exceptions, though, like the cameraman that was sent out to document the fireworks on New Year’s Day 2000. The camera was turned on prematurely. The batteries were used up by midnight, but ‘certain gray tones, however, filtered through the cracks of its protective case, conveyed the motion of the walking cameraman, the transportation. The incompletely shut, low-information container was documented exactly […] To this day it provides inexact testimony as to the qualities of the leather of a twenty-first century carrying case and the precise sensitivity to light and dark demonstrated by a twenty-first century recording medium.’2

Lerner, B., Kluge, A. The Snows of Venice. Leipzig: Spector Books, 2018, p. 53

Ibid.

December, 1947. Rapid snowmelt coincides with torrential precipitation. At the bottom of the Thur valley, in Wildenstein, the water gathers.