What constitutes a ‘document’ and how does it function?

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the etymological origin is the Latin ‘documentum’, meaning ‘lesson, proof, instance, specimen’. As a verb, it is ‘to prove or support (something) by documentary evidence’, and ‘to provide with documents’. The online version of the OED includes a draft addition, whereby a document (as a noun) is ‘a collection of data in digital form that is considered a single item and typically has a unique filename by which it can be stored, retrieved, or transmitted (as a file, a spreadsheet, or a graphic)’. The current use of the noun ‘document’ is defined as ‘something written, inscribed, etc., which furnishes evidence or information upon any subject, as a manuscript, title-deed, tomb-stone, coin, picture, etc.’ (emphasis added).

Both ‘something’ and that first ‘etc.’ leave ample room for discussion. A document doubts whether it functions as something unique, or as something reproducible. A passport is a document, but a flyer equally so. Moreover, there is a circular reasoning: to document is ‘to provide with documents’. Defining (the functioning of) a document most likely involves ideas of communication, information, evidence, inscriptions, and implies notions of objectivity and neutrality – but the document is neither reducible to one of them, nor is it equal to their sum. It is hard to pinpoint it, as it disperses into and is affected by other fields: it is intrinsically tied to the history of media and to important currents in literature, photography and art; it is linked to epistemic and power structures. However ubiquitous it is, as an often tangible thing in our environment, and as a concept, a document deranges.

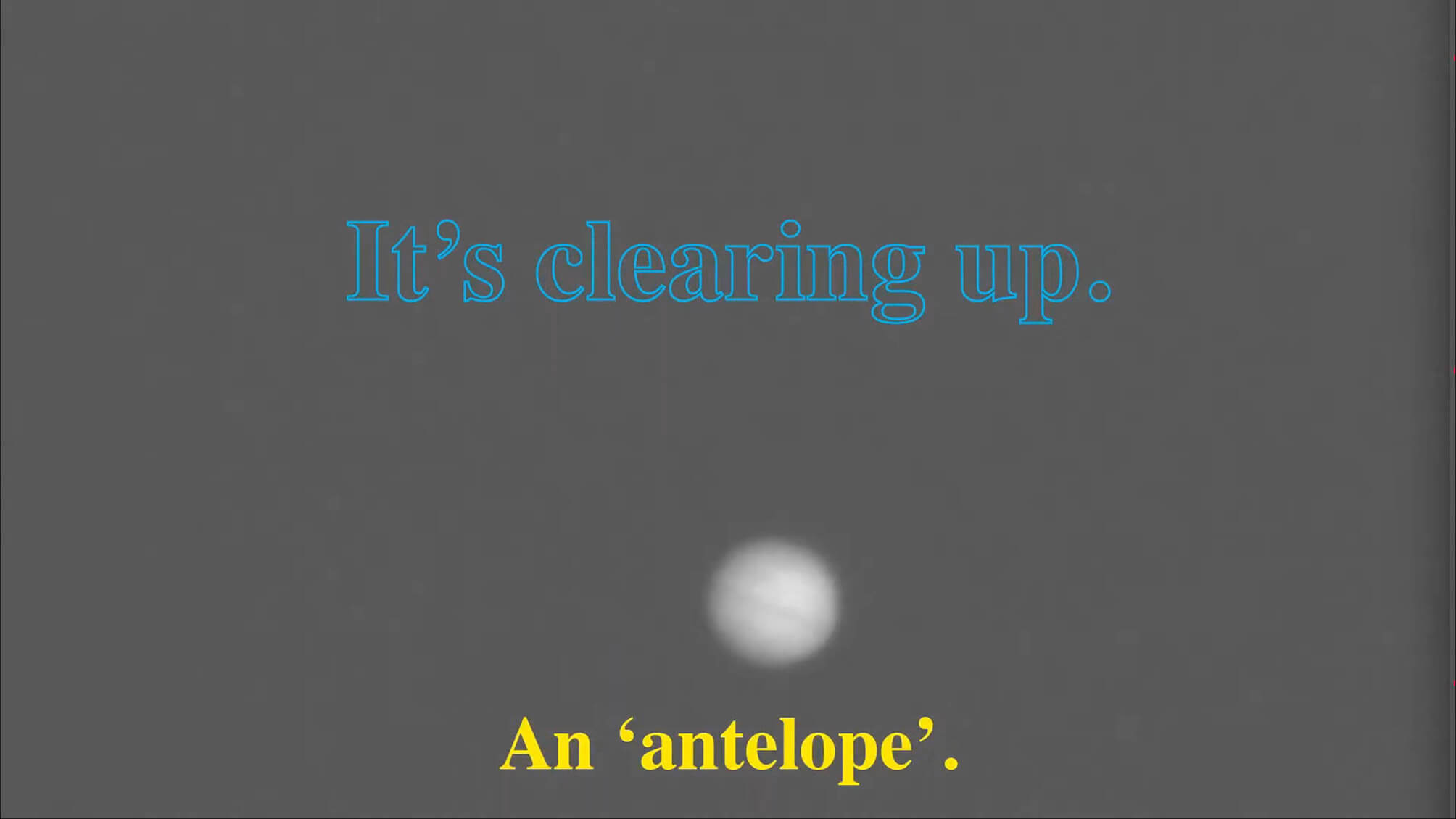

the-documents.org continuously gathers documents and provides them with a short textual description, explanation,

or digression, written by multiple authors. In Paper Knowledge, Lisa Gitelman paraphrases ‘documentalist’ Suzanne Briet, stating that ‘an antelope running wild would not be a document, but an antelope taken into a zoo would be one, presumably because it would then be framed – or reframed – as an example, specimen, or instance’. The gathered files are all documents – if they weren’t before publication, they now are. That is what the-documents.org, irreversibly, does. It is a zoo turning an antelope into an ‘antelope’.

As you made your way through the collection,

the-documents.org tracked the entries you viewed.

It documented your path through the website.

As such, the time spent on the-documents.org turned

into this – a new document.

This document was compiled by ____ on 08.02.2022 11:18, printed on ____ and contains 56 documents on _ pages.

(https://the-documents.org/log/08-02-2022-3780/)

the-documents.org is a project created and edited by De Cleene De Cleene; design & development by atelier Haegeman Temmerman.

the-documents.org has been online since 23.05.2021.

- De Cleene De Cleene is Michiel De Cleene and Arnout De Cleene. Together they form a research group that focusses on novel ways of approaching the everyday, by artistic means and from a cultural and critical perspective.

www.decleenedecleene.be / info@decleenedecleene.be - This project was made possible with the support of the Flemish Government and KASK & Conservatorium, the school of arts of HOGENT and Howest. It is part of the research project Documenting Objects, financed by the HOGENT Arts Research Fund.

- Briet, S. Qu’est-ce que la documentation? Paris: Edit, 1951.

- Gitelman, L. Paper Knowledge. Toward a Media History of Documents.

Durham/ London: Duke University Press, 2014. - Oxford English Dictionary Online. Accessed on 13.05.2021.

At a dental practice, the white Alligat®-powder is mixed with the right amount of water to get a mouldable dough that is pressed upon a patient’s teeth. After thirty seconds, the Alligat®-dough stiffens and takes on a rubber-like quality. At that point, still white, it must be removed from the patient’s mouth. Over the next few hours, the mould turns increasingly pink as the substance becomes less humid. Now, it can be used as a mould to create a positive master cast of the patient’s teeth.

Outside the dental practice, the powder’s possibilities remain to be fully explored.

First published as part of De Cleene De Cleene. ‘Amidst the Fire, I Was Not Burnt’, Trigger (Special issue: Uncertainty), 2. FOMU/Fw:Books, 25-30

Article 75 of the Royal Decree containing general regulations for road traffic and the use of public roads, published in Het Belgisch Staatsblad on 9 December 1975, lists the rules for longitudinal markings indicating the edge of the roadway.

According to 75.1, there are two types of markings that indicate the actual edge of the roadway: a white, continuous stripe and a yellow interrupted line. The former is mainly used to make the edge of the roadway more visible; the latter indicates that parking along it is prohibited.

In 75.2, the decree focuses on markings that indicate the imaginary edge of the roadway. Only a broad, white, continuous stripe is permitted for this purpose. The part of the public road on the other side of this line is reserved for standing still and parking, except on motorways and expressways.

https://wegcode.be/wetteksten/secties/kb/wegcode/262-art75

It’s early spring. The pool is covered with a sheet of plastic. The deciduous trees are just leafing out. A tree stump serves as a placeholder for the diving board’s foot – it was customary to take it indoors for winter – and keeps people from kicking its threaded rods sticking up from the silex tiles that line the pool.

The upper right corner of the plastic frame is missing. It’s probably where the insect – now dead, dry and yellowish – got in. The frame was left behind in the laundry room overlooking the garden, the pool and the pool house. At the time it hadn’t been used for quite a while. Half empty, the water green.

In summer, when the wind dropped, horse-flies came. You could shake them off temporarily by swimming a few meters underwater.

Holding two cans of spray paint, a city employee walks through a sweet chestnut grove on the graveyard. He’s looking for potholes.

On the second to last day of a research visit at CERN, there was some spare time in the schedule. I took a long walk towards building 282 in search of some excavation samples: cylindrical pieces of rock that were preserved when the tunnel was dug, glued to a block of wood and frequently exhibited in museums over the last three decades as material evidence of the earthwork and as a witness to the depth. The route led me along the back of building 363 where the wind caused young trees – now gone – to scuff the facade over time.

First published in: De Cleene, M. Reference Guide. Amsterdam: Roma Publications, 2019, as W.569.EXC CERN, Towards Building 282, in search of excavation samples

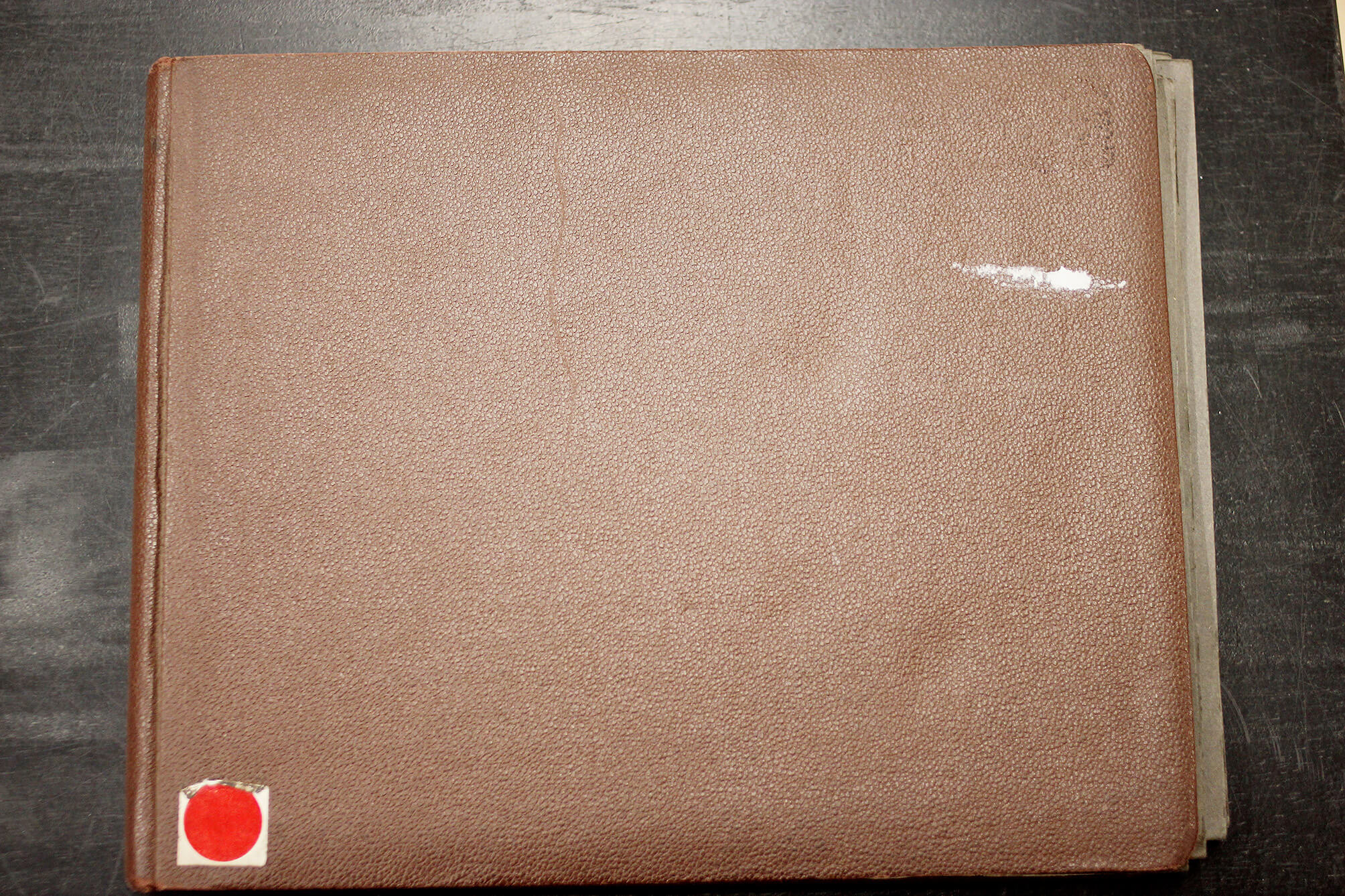

I’m taking a scan of a family photo album given to me after my grandmother passed away, wanting to write something about the marvelous portraits inside. The genealogy is only partly clear to me: I recognize my dad as a kid, my uncle, my grandmother, her brother in the laboratory he (said he) ran. He smelled of cigars and severe perfume. The older photographs present people I don’t know, but must be my ancestors. My grandmother told me stories1 that, historically, reach further back than the figures I recognize in the photographs. There are no names and no dates in the album. The first two pictures seem to be the oldest ones.2 I retract them from the album pockets in which they were slid to check if something is written on the backside. When I take the album away from the scanner’s glass plate, particles of leather, gold varnish and sturdy cardboard come loose. I place a sheet of paper on the glass plate and press ‘scan’ again.

Once she (my grandmother) went home from school, sick, with her bicycle. She studied to become a nurse. The school was in Brussels, about 60 kilometers from her native village M. The milkman’s van tipping over in front of my grandmother’s parental house. A milk covered street. My great-grandfather, physician and mayor at M. Something happened during the Second World War having to do with telephones or radios when she was still a kid.

A block of concrete. Fissures are showing and rebar is sticking out from all sides. If it were still straight, the block would measure approximately 130 x 15 x 40cm.

It is lying by the side of the road, a few hundred meters from a construction site. It appears to be shaped by impact. Maybe the block plummeted to the ground from a great height. Perhaps, something heavy hit it. For all one knows, it served as a column and was exposed to an unforeseen amount of pressure, causing it to buckle.

According to Eyal Weizman ‘[a]rchitecture emerges as a documentary form, not because photographs of it circulate in the public domain but rather because it performs variations on the following three things: it registers the effect of force fields, it contains or stores these forces in material deformations, and, with the help of other mediating technologies and the forum, it transmits this information further.’1

Weizman, E. ‘Introduction’, in: Forensic Architecture. Forensis. The Architecture of Public Truth. London/Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2014.

As a result of intense drainage of drinking water, an area around the Belgian city of Waver was designated as having a potential for land subsidence – the downward movement of the soil over an extended period of time. People in Waver were startled to find their town mentioned in an international study published in Science. Flemish newspaper De Standaard uncovered that the researchers had used an older study, published in 2005, which claimed that the soil in Waver had moved some five centimeters in a period of eleven years. Pictures of fissures in Waver-facades had been added to the original article.

Last year, cracks in our living room wall were covered up by placing plasterboard in front of the plastered brick wall. As such, we avoided having to paint the wall with the cracks and the marks left by the IKEA Billy bookcases.

https://science.sciencemag.org/content/sci/suppl/2020/12/29/371.6524.34.DC1/abb8549_Herrera_SM.pdf

https://www.standaard.be/cnt/dmf20210106_97889104

http://earth.esa.int/fringe2005/proceedings/papers/677_devleeschouwer.pdf

A square photograph with an Arabic and French text underneath it is mounted on a foam board, in turn mounted on a sheet of plexiglass. The picture in the middle is flanked by a photograph of and a text about the tumuli of Umm Jidr (left) and the excavations at Abou Saybi (right). They are mounted on the West wall of Guest Room 3 at the Qual’at Al-Bahrain Site Museum, Seef, Bahrain.

Necropolises make up the main archaeological testimonies of the Tylos period (4th century BC – 3rd century AD). The urn in the photograph contains the remains of several babies. They most likely fell victim to an epidemic. The size of the ruler next to the urn remains unspecified.

The photograph of Room 3 was made while in mandatory self-isolation after flying to Bahrain from Frankfurt and waiting for the result of a Covid-19 test.

Besides the scale indicating the length in centimeters, and the marks made by using it, a folding ruler displays other marks. These are the marks found on the weber broutin www.weber-broutin.be folding ruler, from left to right:

- 2m (in a frame, between 1cm and 2cm); indicating the total length of the folding ruler.

- a hexagon, barely visible, punched into the wood (between 2cm and 3cm); unknown signification.

- LUXMA (in a frame, between 4cm and 5cm); the manufacturer of the folding ruler (different from the company who ordered the folding ruler, their (the company’s, i.c. weber-broutin’s) name is printed on the sides of the ruler, and is only readable when the ruler is folded together for at least 50% (=1m).

- III (in an oval, between 6cm and 7cm); indication of the preciseness of the scale in centimeters, with ‘I’ in roman numbers meaning the most precise, and ‘IV’ in roman numbers meaning the least precise. (It is therefore not entirely certain that the ‘III’ on weber-broutin’s folding ruler can actually be found between 6cm and 7cm.)

- D 99 (in an oval, probably between 7cm and 8cm, see argument mentioned above); unknown signification.

- 1.1.60 (in an oval, probably between 7cm and 8cm, beneath D 99), signification unknown.

Depending on the language one chooses, the Wikipedia entry for ‘document’ shows a different picture. The French-language page shows what appears to be a Slovenian thesis written in 1984. The caption states it is a ‘book of Czechoslovak computer science author Květoslav Šoustal about computer networks’. The image was uploaded by Kelovy, a Slovakian mushroom-picker.

The anonymous hand rests on a lemon-yellow tablecloth, on which a yellow book and a blue binded file lie. The top left corner is the most intriguing, however: the tablecloth seems to be draped over a lemon, alongside a drinking glass. The cloth, however, does not get shaped by the lemon. Nor does the shadow-side of the lemon coincide with the shadow the other documents throw on the tablecloth. A closer look seems to indicate that the lemon is in fact an image of a lemon, printed on a plastic napkin.

The Russian wikipedia shows the image of a lease agreement. The German wikipedia for ‘document’ is text only.

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Document#/media/Fichier:KVETOSLAV_SOUSTAL_BOOK.JPG, created October 3, 2006 / original in original: paper, 1984

I must have driven past this rocky landscape about sixteen times, going back and forth between viewpoints and the house the parents of a friend let me stay in. On the last day, I left early for the airport, pulled into a lay-by, took my tripod and camera out of the trunk of the red Volkswagen Polo rental car and made two photographs.1 It was only when I got home, had the film developed, scanned it and was removing dust particles from the file, that I discovered the hand painted text on the rock: ‘PROIBIDO BUSCAR SETAS’.

Ten years ago, in November, I drove up to Frisia – the northernmost province of The Netherlands. I was there to document the remains of air watchtowers: a network of 276 towers that were built in the fifties and sixties to warn the troops and population of possible aerial danger coming from the Soviet Union. It was very windy. The camera shook heavily. The poplars surrounding the concrete tower leaned heavily to one side.

I drove up to the seaside, a few kilometers farther. The wind was still strong when I reached the grassy dike that overlooked the kite-filled beach. I exposed the last piece of film left on the roll. Strong gusts of wind blew landwards.

Months later I didn’t bother to blow off the dust that had settled on the film before scanning it. A photograph without use, with low resolution, made for the sake of the archive’s completeness.

The dust on the film appears to be carried landwards, by the same gust of wind lifting the kites.

A Sunday stroll near my parents’ house. Along one of the roads between the fields, old poplars have been felled. Young trees have been planted. Each one has a baby blue coloured label, identifying them as Poplar tree, and, more specifically, the ‘Vesten’ cultivar. This cultivar is planted since it is one of the cultivars known for its resistance with regards to bacteria, diseases and insects. The tags on the trunks have staples keeping them together. They’re like bracelets. Come spring, the expanding diameter of the fast growing poplar species’ trunk will tear them apart.

Steenackers, M., Schamp, K., & De Clercq, W. (2018). De INBO variëteiten van populier, een aanwinst voor de Europese populierenteelt. Silva belgica : tijdschrift van de koninklijke belgische bosbouwmaatschappij = bulletin de la société royale forestière de belgique, N°4/2018, 40-47. [5].

https://purews.inbo.be/ws/portalfiles/portal/15044340/Dossier_populier_INBO_KBBM.pdf

The oldest coin in the collection has darkened over time, but upon inspection, the text ‘AD USUM BELGII AUSTR’ (left) and the contours of a (female) head (right) can be discerned. A quick search learns it stems from the middle of the 18th century. The coin was made and used in the Austrian Netherlands, reigned by Maria Theresa, who is the one depicted. My mother recollects finding it in the backyard when she was a kid.

About 40 years later, the euro was introduced. The ringbinder with my mother’s coin collection was taken from the shelf. A dilemma came to the fore: we wondered if we should keep one of each existing Belgian coin and banknote and put them in the binder, alongside Maria Theresa, or if we should exchange them for the new European currency. The decision to keep a coin of five Belgian francs was not difficult to make, but as the amount raised, the answer was increasingly hard to give. This was an assessment of the old currency’s emotional and projected historical value, compared to its current financial worth. It was a decision based on investment principles.

To accentuate the value of the Maria Theresa kronenthaler of 1 liard, I put the coin on a pile of red post-it-notes when photographing it. Coins like these are sold on eBay for prices ranging from 0,70 euros to 16 euros.

A 250 meter walk away from the seaside. A sign states in Dutch and French:

‘!!! NO PARKING !!!

Wrongly parked cars will be chained and only released upon payment of a € 40 parking fee’

The 40 EUR parking fee the sign threatens to charge is communicated by a relatively new sticker stuck on an older sign. Underneath the three black characters (€, 4 and 0) on a white background, there’s a relief: 7 characters declaring a parking fee of 1500 BEF.

1500 BEF equals 37,18 EUR1. In changing currency, the fee increased by 7,58%.

The Belgian franc was the currency of the Kingdom of Belgium from 1832 until 2002 when the Euro was introduced. 1 EUR is worth 40,3399 BEF.

K. says that the stall where he usually buys fruit has already been packed up. But he is not worried about the quality of the fruit the other vendor sells. He gestures encouragingly.

Five signs of type-1, eleven of type-2 and two of type-3 are visible. Four of type-2 (two visible, two deduced) and two of type-3 retain two vehicles.

Márk Redele pursues projects that fundamentally relate to architecture and its practice but rarely look like architecture. www.markredele.com

Depending on the language one chooses, the Wikipedia entry for ‘document’ shows a different picture. The French-language page shows what appears to be a Slovenian thesis written in 1984. The caption states it is a ‘book of Czechoslovak computer science author Květoslav Šoustal about computer networks’. The image was uploaded by Kelovy, a Slovakian mushroom-picker.

The anonymous hand rests on a lemon-yellow tablecloth, on which a yellow book and a blue binded file lie. The top left corner is the most intriguing, however: the tablecloth seems to be draped over a lemon, alongside a drinking glass. The cloth, however, does not get shaped by the lemon. Nor does the shadow-side of the lemon coincide with the shadow the other documents throw on the tablecloth. A closer look seems to indicate that the lemon is in fact an image of a lemon, printed on a plastic napkin.

The Russian wikipedia shows the image of a lease agreement. The German wikipedia for ‘document’ is text only.

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Document#/media/Fichier:KVETOSLAV_SOUSTAL_BOOK.JPG, created October 3, 2006 / original in original: paper, 1984

(‘Imaginary landscape in the actual greater Gent, some thousands of years ago. A grassy riparian zone separates rivers from the edge of the forests’)

Imagine a deserted city of Gent, overtaken by nature, Thiery asks the reader in his book Het woud (The Forest). After fifty years, you return to the city. Buildings have collapsed, streets are overgrown. It has become an impenetrable, dense forest, except for the river on which the reader makes his or her way through it. In the first half of the twentieth century, Leo Michel Thiery made one of Belgium’s first botanical gardens for educational purposes. In the middle of an industrialized quarter of the city of Gent, the garden presented different sceneries. There were landscapes from the Alps, dunes, the Ardennes, steppe. Besides sceneries with chalk-, loam-, marl- and sand-based vegetation, there were forests, grasslands and swamps.

After his death, Thiery’s garden decayed. Decades later, it was restored, with the Alps, dunes, the Ardennes and steppe now classified as a protected view.

Thiery, M. Het woud. Een proeve van plantenaardrijkskunde. Gent: De Garve, s.d., p. 14

(‘Slice of more than three meters in diameter, sawn from a Mammoth-tree, given by California to the botanical garden of New York, and presented there’)

Thiery describes the ‘patriarchs’ of the plant world. This slice of a Sequoia, which fell in 1917 in Yosemite National Park, is 1694 years old. A woman of the New York Botanical Institue, where the slice of the patriarch is presented, counted the rings. If one would look at the picture with a magnifying glass, Thiery writes in a footnote, the reader (with good eyes and a fair amount of knowledge of the English language) would be able to read the labels indicating the important global events the tree witnessed. They are transcribed and translated by the author. The end of the Roman occupation of Great Britain. Columbus arriving in America. The Declaration of Independence. This is a lie: the text is illegible, even when using a magnifier.

In the photograph, the slice, as on view in the New York Botanical Institute, is presented upright. To prevent it from rolling away, two small triangular slices of wood were posited at the left and right side of the slice. The type of wood of these slices, nor the age of the patriarch from which they stem, are known.

Thiery, M. Het woud. Een proeve van plantenaardrijkskunde. Gent: De Garve, s.d., p. 59.

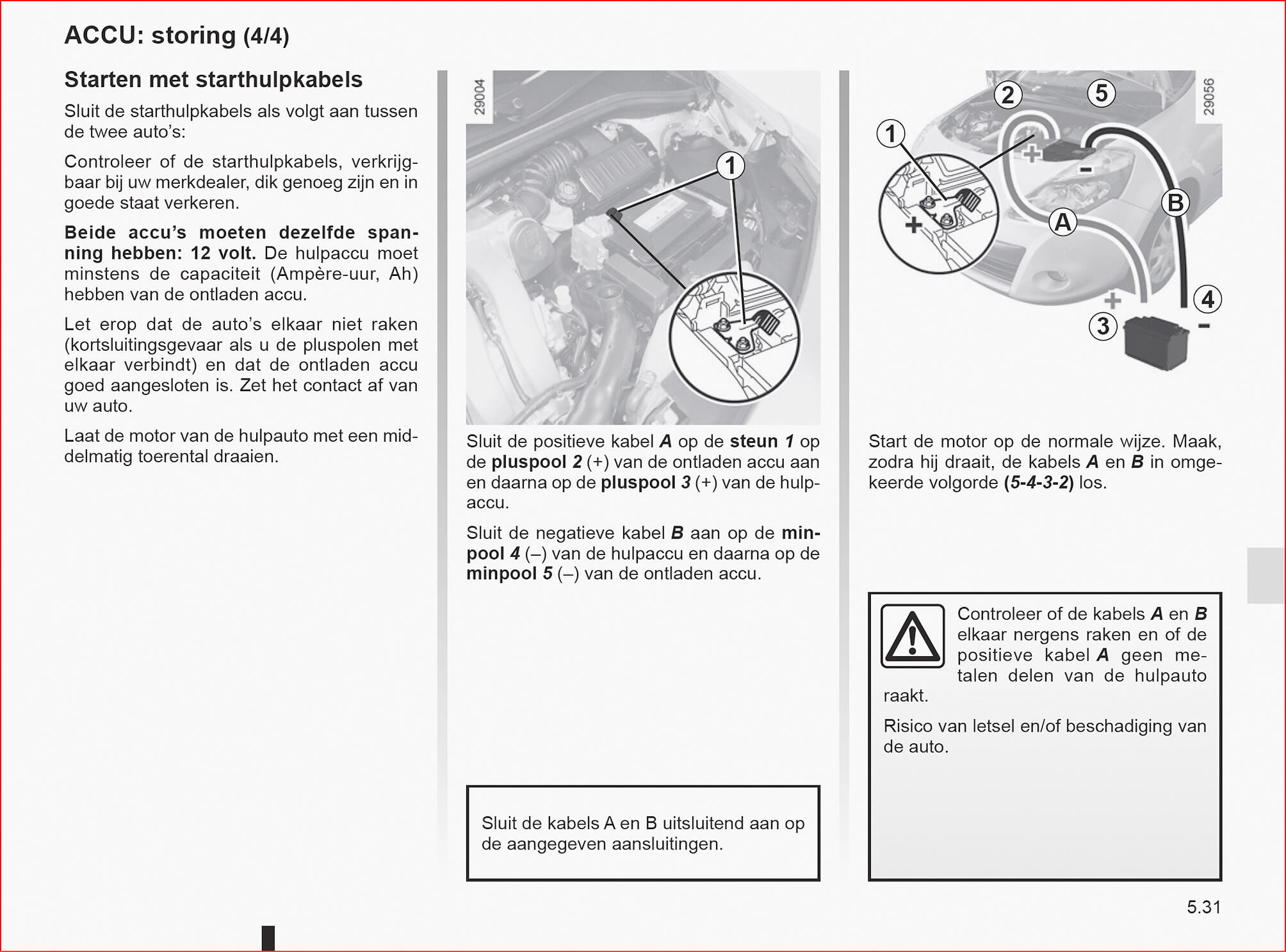

Due to strict regulations during the COVID-19-pandemic, the yearly vehicle inspection had to be scheduled by appointment. Getting ready to drive to the DMV, the car wouldn’t start. It had rained heavily, the preceding days. The day before the DMV-appointment, water had come running into the car on pushing the pedals. My socks were wet.

I called the DMV to say I needed to cancel the appointment and make a new one (but that the car, besides not being able to drive, was perfectly fine, vehicle-inspection-wise).

Later that day, we got the engine up and running again, using jumper cables and a second car, so we would be able to drive to meet the midwife the next day.

Renault Clio. Instructieboekje. 2012. PDF-file

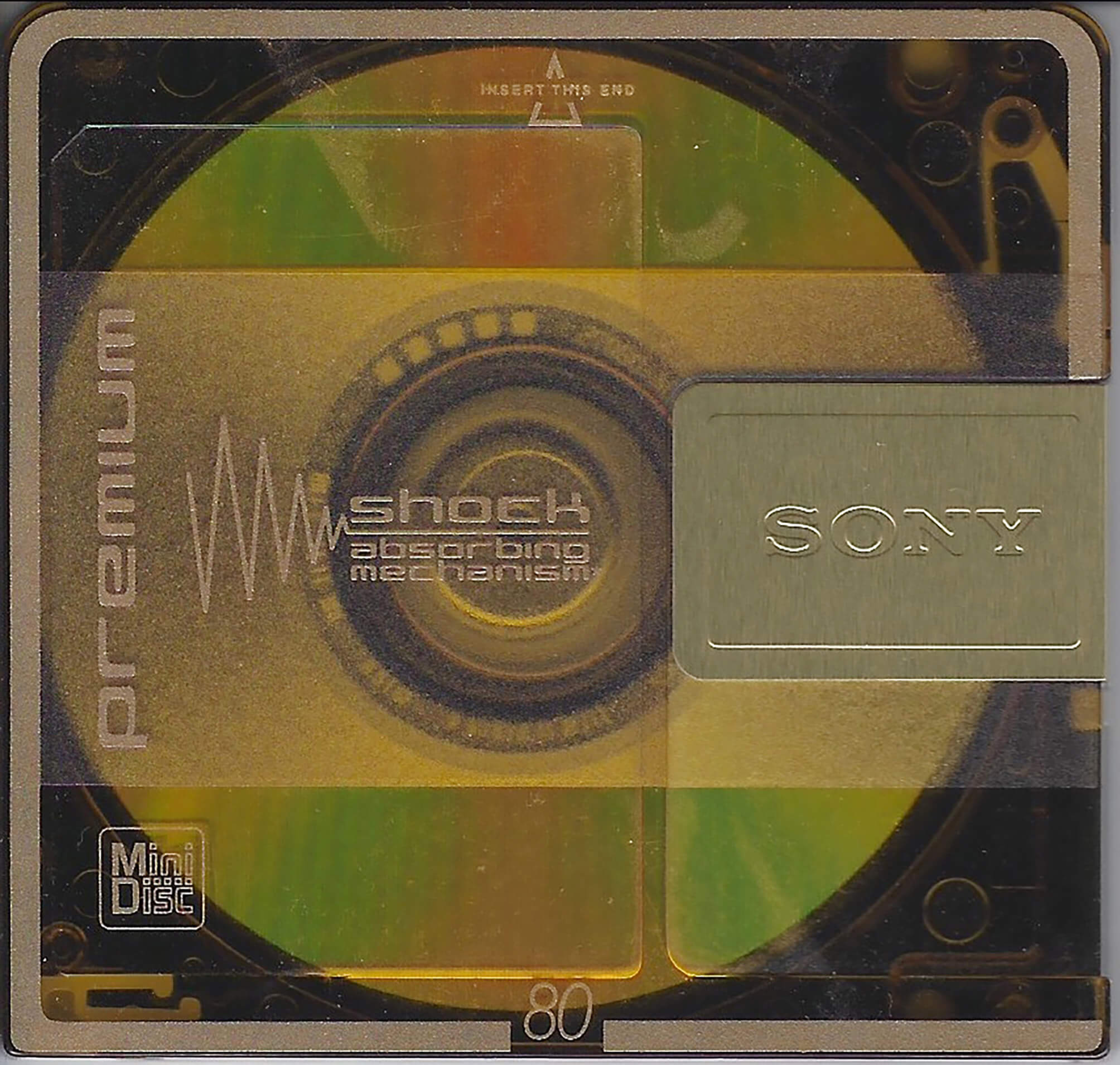

‘Because there is a kind of technological beauty to it.’

[…]

‘Yes, a perfect combination of the analogous on the one hand, and a kind of state of the art-futuristic cool on the other hand. It was elegant (unlike audio-cassettes), you could see the disc upon which your music was written (unlike the unfathomable MP3), it was less fragile than a CD(-R), and conveniently sized (you could hold it in the palm of your hand, slip it into your pocket). It had a kind of Mission Impossible-esque gadget feel to it. It had the aura of being permanently ahead of its time, but not in a far-fetched sci-fi kind of way. It was real.’

[…]

‘You mean the clicks. Yes, it had a sound of its own. A pleasant sound – the hard plastic hitting the hard plastic sleeve. The slidable, uhm, metal thing. The small read/write handle at the side. The small disc that was just a little bit loose. It – without being played – looked, felt and sounded like, like data, yes, like palpable data.’

[…]

‘Not any more.’

[…]

‘My uncle’s Elvis Costello This Year’s Model LP with way too little bass-sounds. Watching the detectives, to be precise.’

At the State Archive in Kortrijk, I am leafing through a 1955 photo album of the construction of the provisional church in Lokeren by the famous furniture company Kunstwerkstede De Coene. Gigantic wooden, prefabricated beams structure the building. It is cold. An old man in a grey suit shuffles between the racks to look up the date of birth of his great great grandmother. Snow covers the unfinished provisional roof. A bus passes, I reckon, through the pouring rain.

During the one day course Safety and Avalanches, teacher G.T. shows pictures of different manifestations of snow and ice. If one learns to read them, one can deduce the wind direction when hiking or skiing in mountainous terrain. Wind direction is crucial for assessing the stability of the snow. G.T.’s examples are of Austrian origin. He speaks about ‘Anraum’: displaced snow can get stacked horizontally against an object, such as a tree or a cross. The snow ‘grows and builds into the wind’. Counter-intuitively, the snow points to the side the wind is coming from. One can expect dangerous terrain in the direction of the ‘unbuilt’ side of the object.

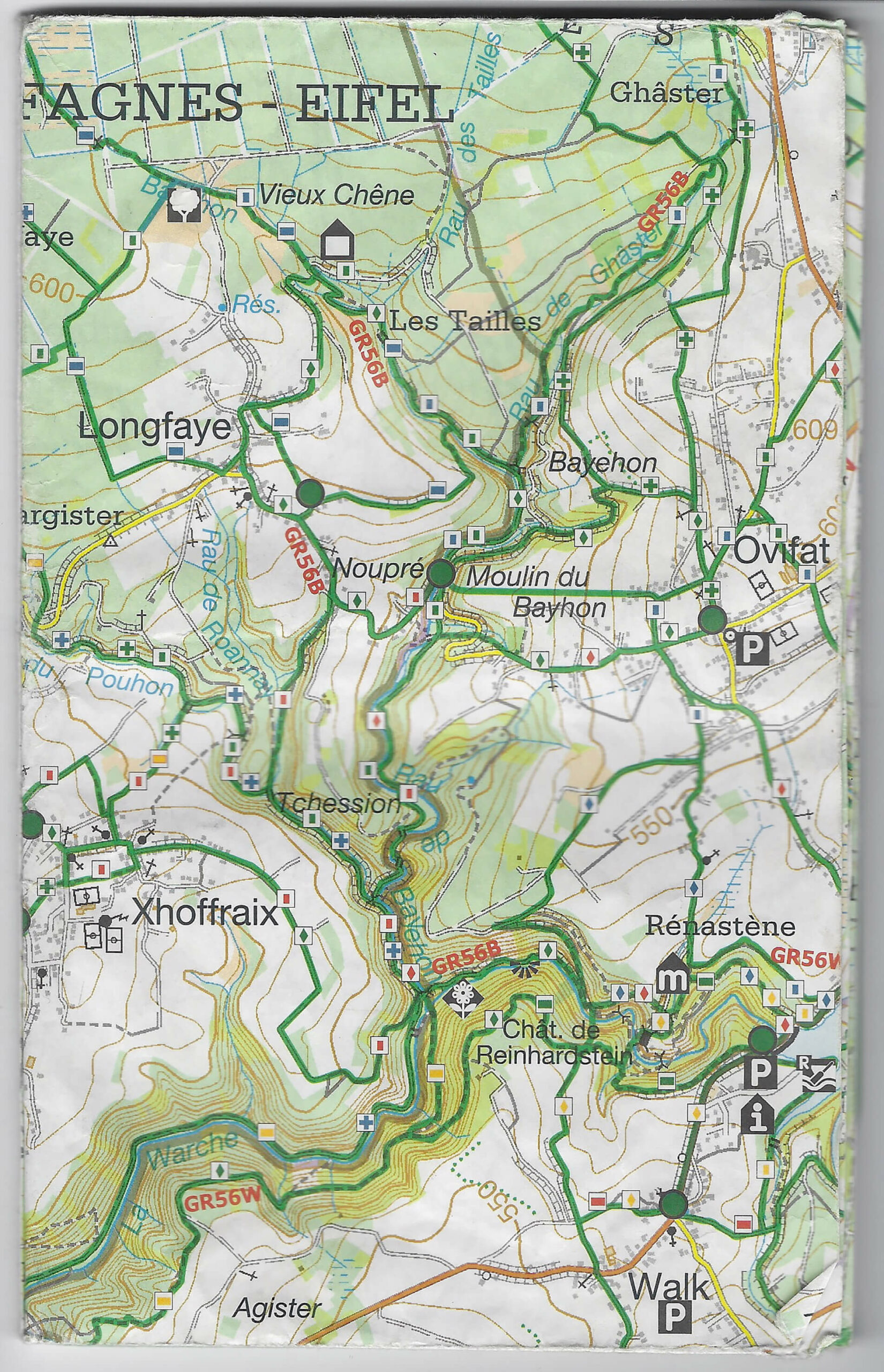

The paths in the valley of the Bayehon are covered with ice. We are making our way down towards the valley of the Ghâster. The temperature is minus 15 degrees Celsius. The water in our drinking bottles is frozen. We are betting on the shelter indicated on the map (Au Pied des Fagnes, Carte De Promenades, 1:25.000, Institut Geographique National) to pitch our tent. There is almost no wind, but every breath of air feels like we’re being hit with a thousand needles. What the map indicates as a shelter appears to be a picnic table.

A year before the crash, Swiss artist Charlotte Stuby designed a tailor-made cover for the car. The dents caused by the unfortunate hailstorm weren’t visible. The work, called Gone Fishing, was on view during an open air exhibition on the theme of the parking lot. Heavy wind had caused the temporary traffic signs on the parking lot, left there by the city services, to tip over. One hit a car and caused a scratch. It was unclear if this would be something the insurance company would accept. We attached Stuby’s cover a second time. Parking fines flew irregularly across the lot.

In June, 2014, a severe hailstorm hit Belgium. Warnings were broadcast. A football game between the national teams of Belgium and Tunisia was paused. The morning after, there were small dents in the hood and the roof of the car, each a square centimeter in size, some 10 centimeters separated from each other. The storm didn’t get a name.

Assessing the damage, the insurance company’s expert took the dents into account to establish the wreck’s worth.

On the online thrift shop 2dehands.be the homepage generates a ‘for you’ section. On November 9th this section listed, among other things, a picture of the sky on a patch of concrete. On closer inspection, it became clear that it was the sky’s reflection in a mirror with a red frame and four lightbulbs in it, the kind you might see at the hairdresser’s or backstage in a television studio or theatre. The seller estimates the mirror’s current value to be 45,00 EUR. The listing includes five photographs. In the fifth one, the object for sale reflects a bucolic landscape: a blue sky, white clouds, some trees and a fragment of a barn.

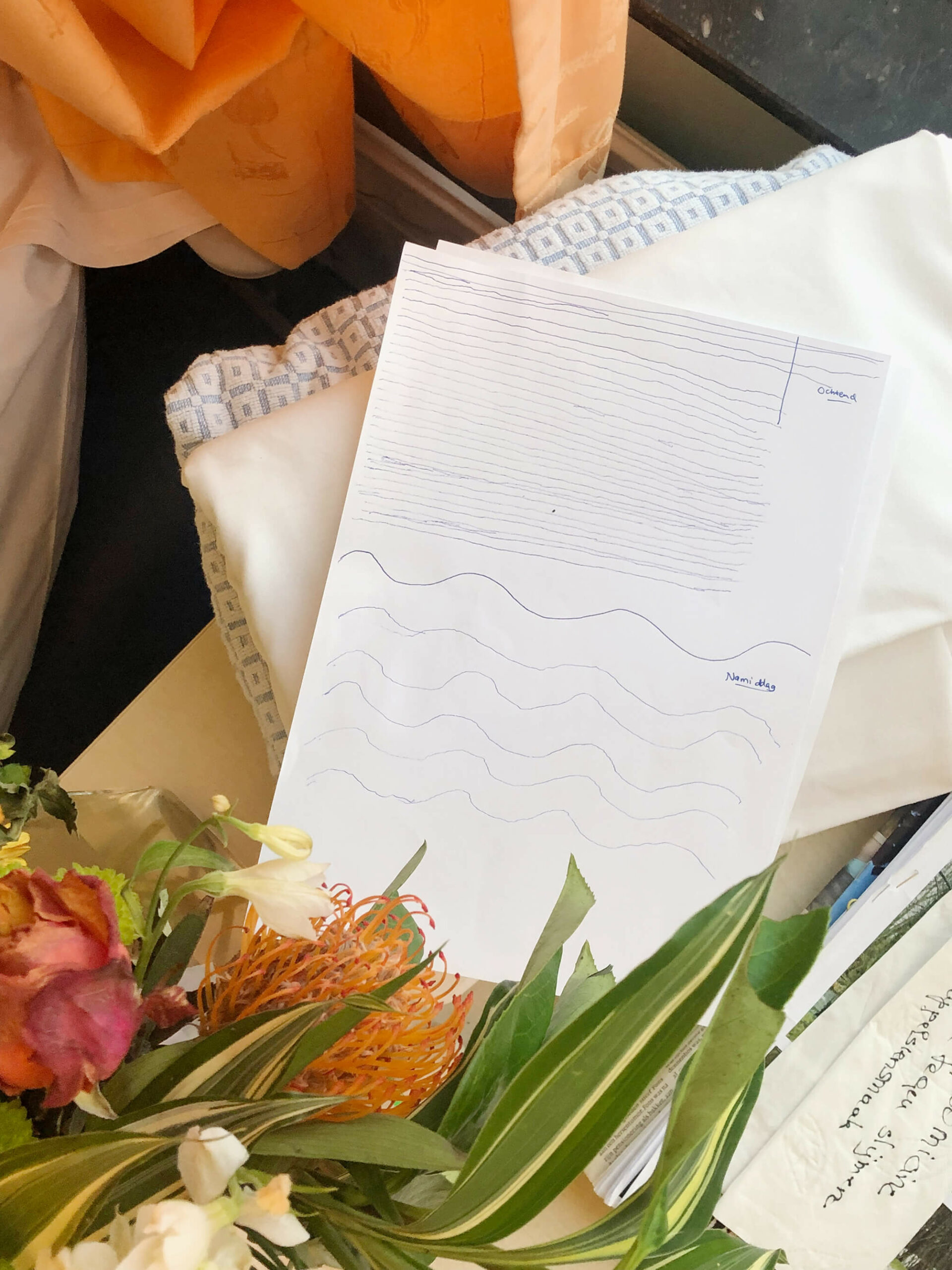

On a pile of fresh hospital sheets, near the radiator, the tangerine curtains and the black marble window sill (the window looks out over the parking lot), underneath the two-day-old bouquet of flowers and next to a pile of magazines with a handwritten note on top (about a syrup that relieves slime and tastes like oranges), lie two sheets of paper.

Earlier that day the physiotherapist had come by. Twice. Once in the morning and once in the afternoon. He had each time drawn the first line, as an example. A straight line in the morning, a curvy line in the afternoon.

With a ballpoint pen my grandfather, who is recovering from an accident, diligently copied the examples (31 in the morning, 5 in the afternoon).

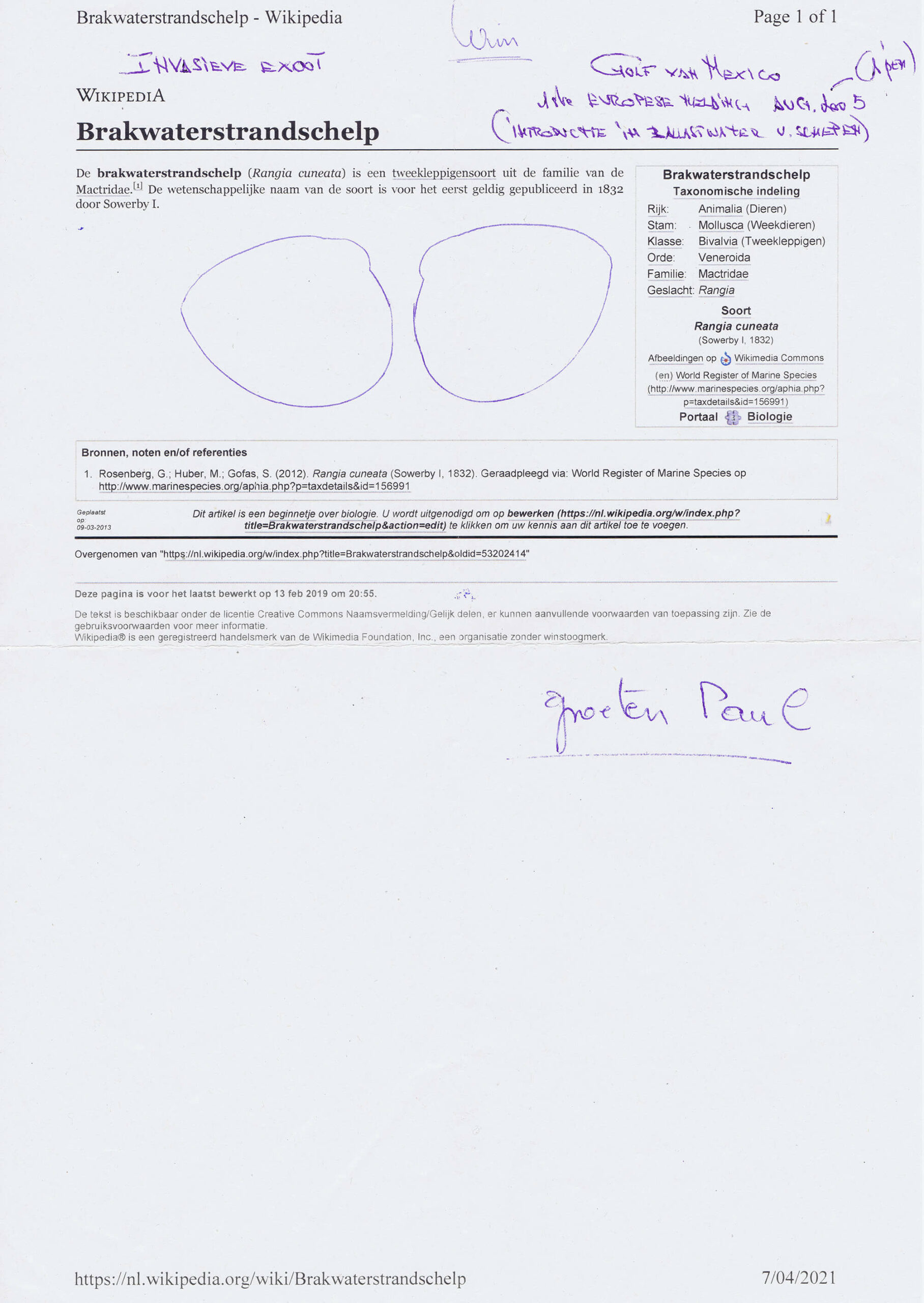

Halfway March my dad started finding empty clam shells on the banks of the Zuidlede along the pasture where he used to herd sheep. He had never seen this type of clam before. There were easily seventy of them along a hundred metre stretch of riverbank.

He brought two specimens to someone he knows in the neighbouring provincial domain. She would look into it, she said, and that she would probably pass it on to someone at the educational department.

Yesterday he (my dad) received a printout of the Dutch wikipedia-page on the Brakwaterstrandschelp (Rangia Cuneata). On the page Paul (who sends his regards at the bottom of the document) traced around the scallops with a blue ballpoint pen.

My dad added in capitals – also with a blue ballpoint pen – that the Rangia Cuneata is an invasive species, native to the Gulf of Mexico. The first time it was observed in Europe was in Antwerp in August 2005, most probably they reached Europe in the ballast water tanks of large ships.

French writer Raymond Queneau did extensive research into what he called hétéroclites, and at other times fous littéraires, a continuation of a longstanding bibliographic project of assembling texts proposing eccentric theories that were never picked up by the scientific community. Disappointed by the results of his research and unable to find a publisher, he abandoned the idea of publishing the encyclopaedia he was compiling. Later, in his encyclopaedic novel Les enfants du limon, he picks up the thread, from a different perspective. It tells the story of two quirky characters, Chambernac and Purpulan, wanting to compile an encyclopedia on fous littéraires. The novel cites from the texts they have dug up. The novel ends when they give up on the project, and give their findings to a novelist they meet and who says to be interested in the material, and asks if it would be OK if he’d attribute it to a character in a story he’s writing. Chambernac agrees, asking the name of the novelist he’s meeting: ‘Monsieur comment?’ – ‘Queneau’.

Queneau, R. Aux confins des ténèbres. Les fous littéraires du XIXe siècle (M. Velguth, red.). Paris: Gallimard, 2002.

Queneau, R. Les enfants du limon. Paris: Gallimard, 2004 [1938].

The building is almost finished. One apartment is still up for sale, on the top floor. The contractor is finishing up. There’s a long list of comments and deficiencies that need to be addressed before the building can be handed over definitively to the owner. The elevator’s walls are protected by styrofoam to prevent squares, levels, measures, drills, air compressors, chairs, bird cages, etc. from making scratches on the brand new wooden panelling.

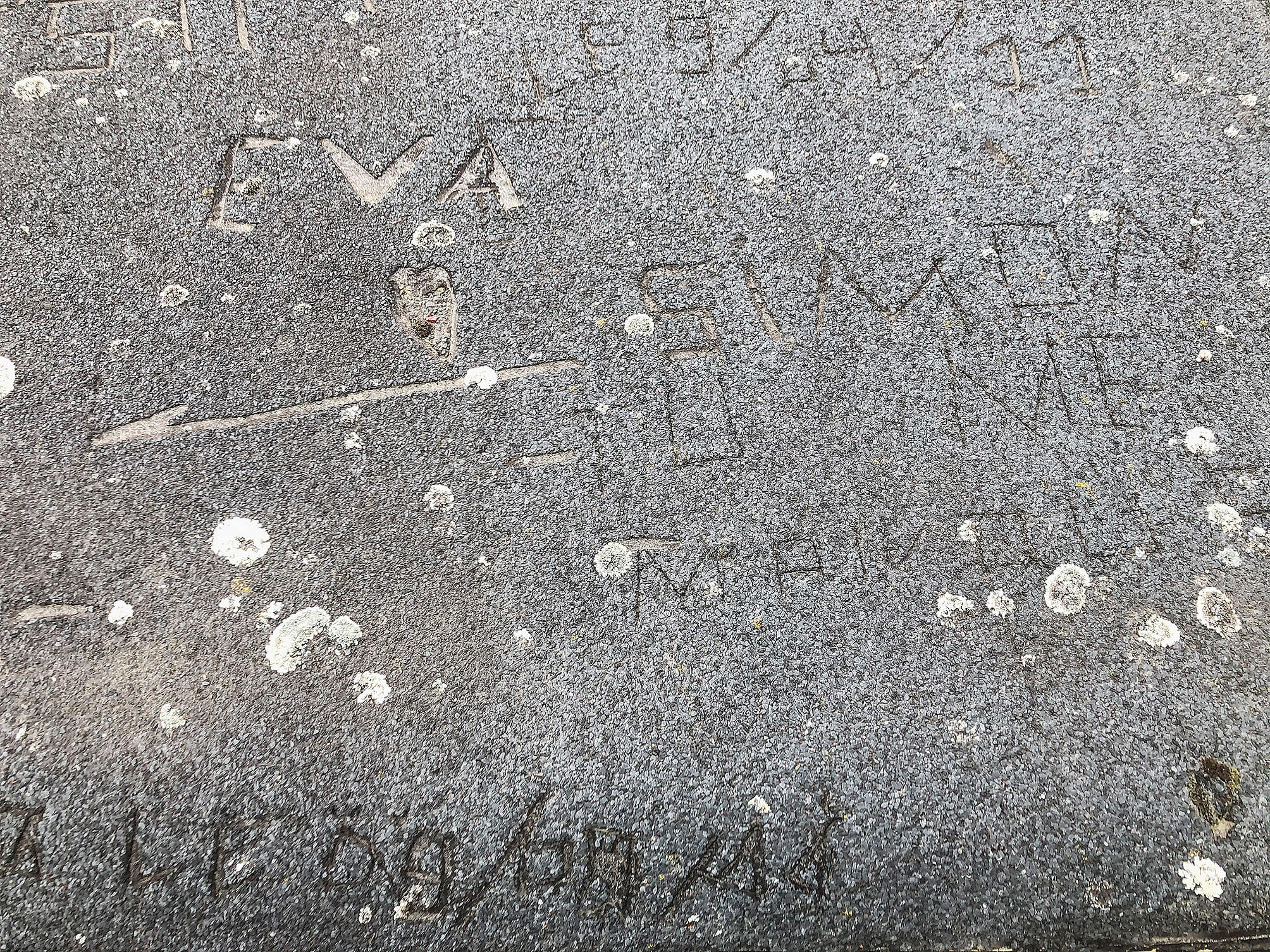

In 1932 Brassaï began taking photographs of graffiti scratched into walls of Parisian buildings. On his long walks he was often accompanied by the author Raymond Queneau, who lived in the same building but on a different floor. Brassaï published a small collection of the photographs in Minotaure, illustrating an article titled ‘Du mur des cavernes au mur d’usine’ [‘From cave wall to factory wall’].

In what order and by whom the various texts and drawings were carved into the soft roofing is unclear. To the right of ‘EVA’, a heart symbol and an arrow (pointing to the left), the roofing reads ‘SIMON TU ME MANQUES’.

The short sentence usually – yet hastily – translates to ‘Simon, I miss you’. However, in French the ‘you’ (tu) is the subject and has an active role, whereas the ‘I’ (me) is the direct object. In short: by his not being there, Simon actively effectuates hurt to the one who carved this text.

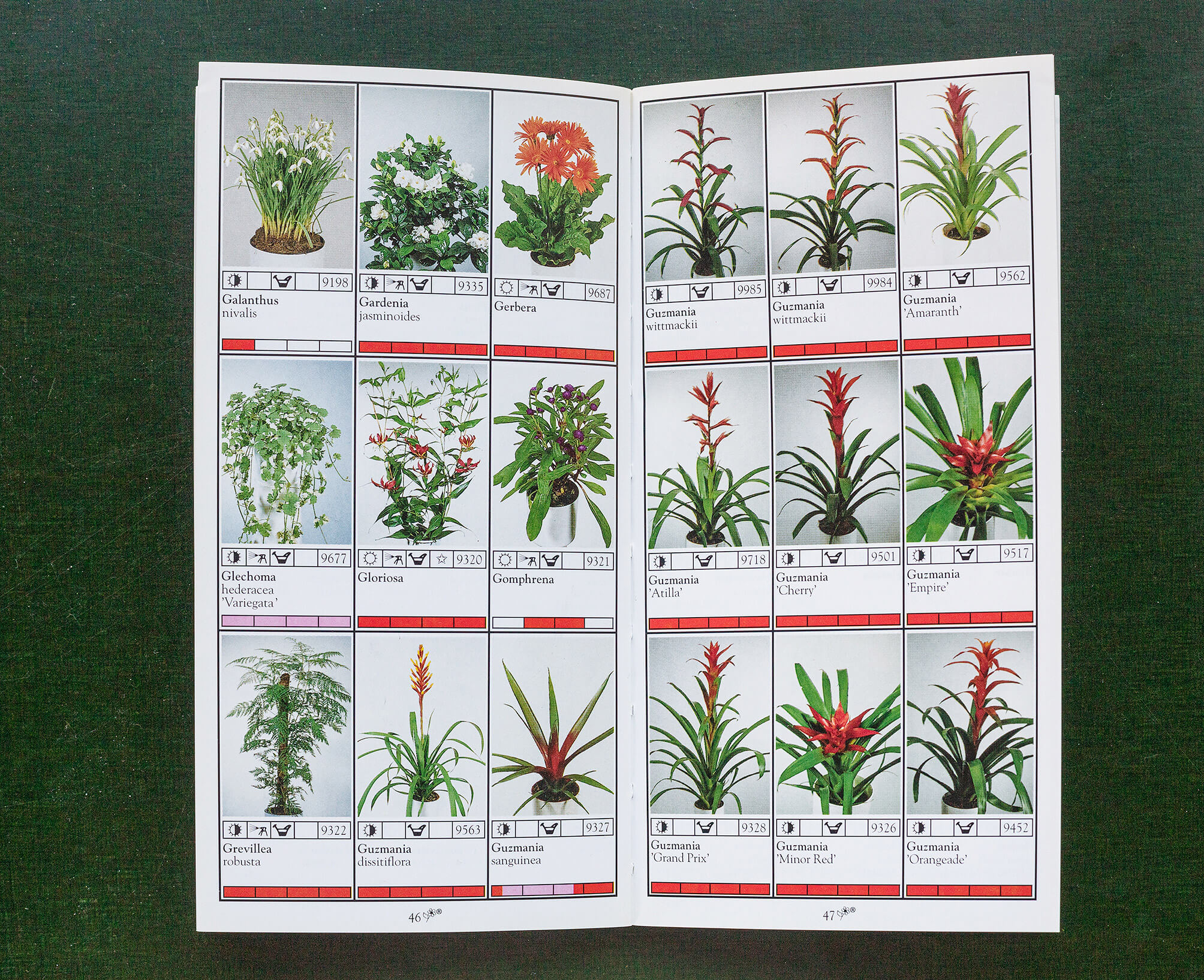

Anastasio Guzmán was a Spanish pharmacist and naturalist. He spent most of his career in South-America. He died in 1807 during an expedition in the Cordillera de Los Llanganates in Ecuador, in search of the lost treasure of the Incas. Some time after his death, his colleague Juan José Tafalla suggested naming a certain genus of plants after his friend.

Guzmanias are mainly stemless, evergreen, epiphytic perennials native to Florida, the West Indies, southern Mexico, Central America, and northern and western South America.They are found at altitudes of up to 3.500m in the Andean rainforests.

The symbols beneath the photographs indicate that these Guzmanias require full light, but it is advised to avoid bright sunlight in spring and summer (HALF WHITE, HALF BLACK SUN), the compost should be kept moderately moist during growth, allowing it to dry slightly between each watering period (HALF FILLED WATERING CAN). Unlike, for instance, the Grevillea Robusta, a Guzmania does not require being sprayed regularly (SPRAYER). The four digit code is the AUCTION CODE: ‘Every product has a code. This code is indispensable for the trade.’ The COLOURED BAR at the bottom shows the availability of a plant quarterly. RED means good, PINK means moderate and WHITE means not available.

The introduction to this booklet mentions that ‘[p]rinted colours are often not as accurate as the colours of the plants themselves, which is why it is possible that colours shown in pictures in this booklet may be a little different from the colours of the real pot plant.’

Bloemenbureau Holland. Potplanten, pot plants, topfpflanzen, plantes en pot, piante da vaso, planta en particular 1995/96. Leiden: Bloemenbureau Holland, 1995.

When the juneberry (Amelanchier Lamarckii) flowers, the beekeeper knows it’s time to add a first honey super to the hive. Winter’s over and worker-foraging bees will fly out and come back with their stomachs full of nectar. To avoid larvae in the honey, the beekeeper will place a grid – the so-called queen excluder – between the main compartment of the hive and the honey super.

A carving that looks like a stitched-up scar (a long, slightly curved line crossed at a right angle by eleven short straight lines) is inserted into a short statement about Celine and Logan. An initial of Celine’s last name is included. At first sight it looks like a ‘D’, but the line through the middle might just as well make it a ‘B’. Maybe it was Celine D who added the line in an attempt to convince those reading the roofing that it’s actually Celine B who blows Logan.

The building is almost finished. One apartment is still up for sale, on the top floor. The contractor is finishing up. There’s a long list of comments and deficiencies that need to be addressed before the building can be handed over definitively to the owner. The elevator’s walls are protected by styrofoam to prevent squares, levels, measures, drills, air compressors, chairs, bird cages, etc. from making scratches on the brand new wooden panelling.

In 1932 Brassaï began taking photographs of graffiti scratched into walls of Parisian buildings. On his long walks he was often accompanied by the author Raymond Queneau, who lived in the same building but on a different floor. Brassaï published a small collection of the photographs in Minotaure, illustrating an article titled ‘Du mur des cavernes au mur d’usine’ [‘From cave wall to factory wall’].

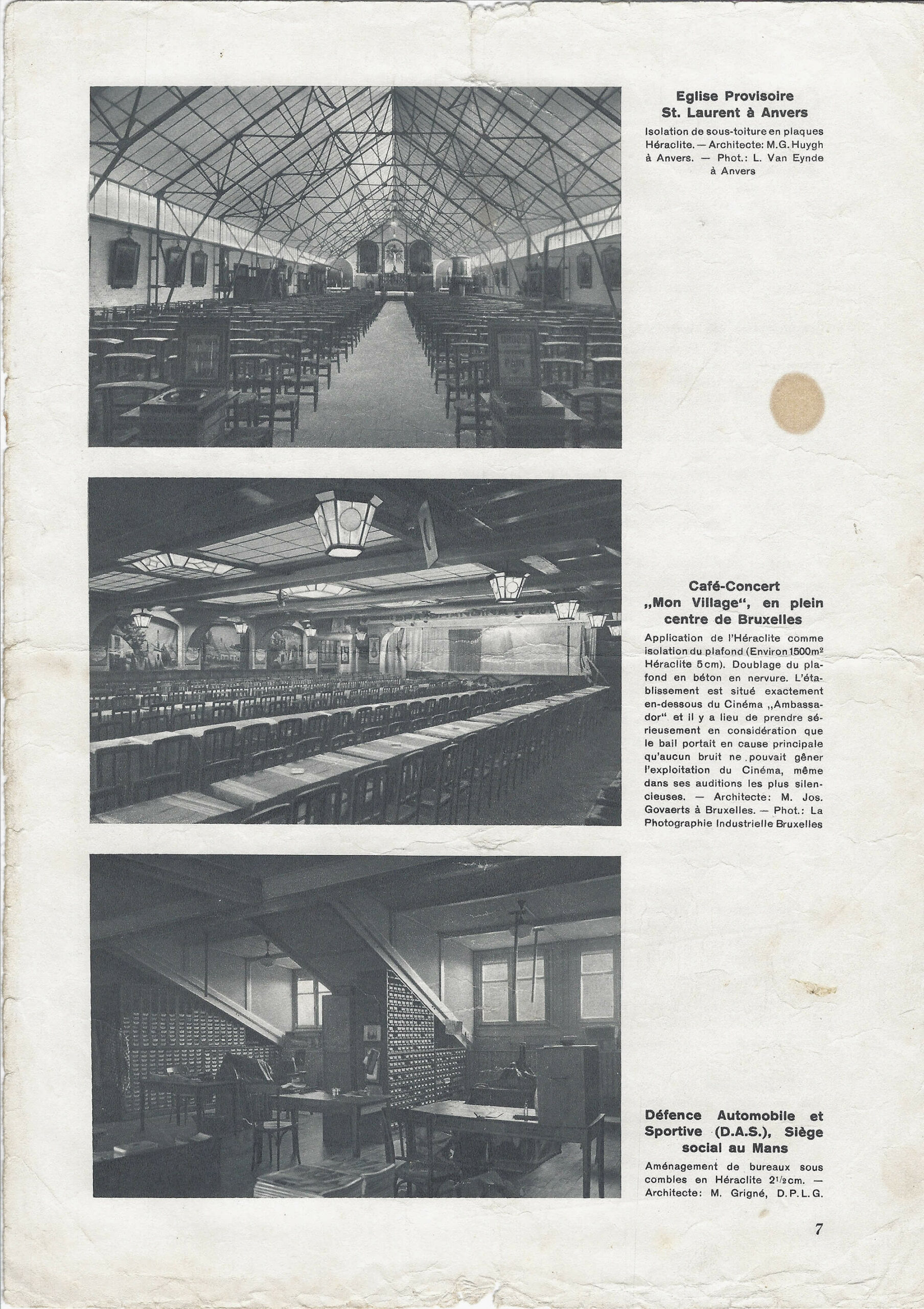

All chairs are empty, but all face something different. The bottom photograph shows empty chairs facing empty desks. In the middle picture, empty chairs face each other (underneath the inaudible sound of the cinema above). In the top photograph, the chairs seem to be facing the photographer. However, the altar’s in front of the photographer. He stands at the back of the provisional church. The chairs face the photographer and have turned their backs to the altar.

Revue Héraclite, 5 (1), april 1936, p. 7, paper, from the archive of architect O. Clemminck.

At the State Archive in Kortrijk, I am leafing through a 1955 photo album of the construction of the provisional church in Lokeren by the famous furniture company Kunstwerkstede De Coene. Gigantic wooden, prefabricated beams structure the building. It is cold. An old man in a grey suit shuffles between the racks to look up the date of birth of his great great grandmother. Snow covers the unfinished provisional roof. A bus passes, I reckon, through the pouring rain.

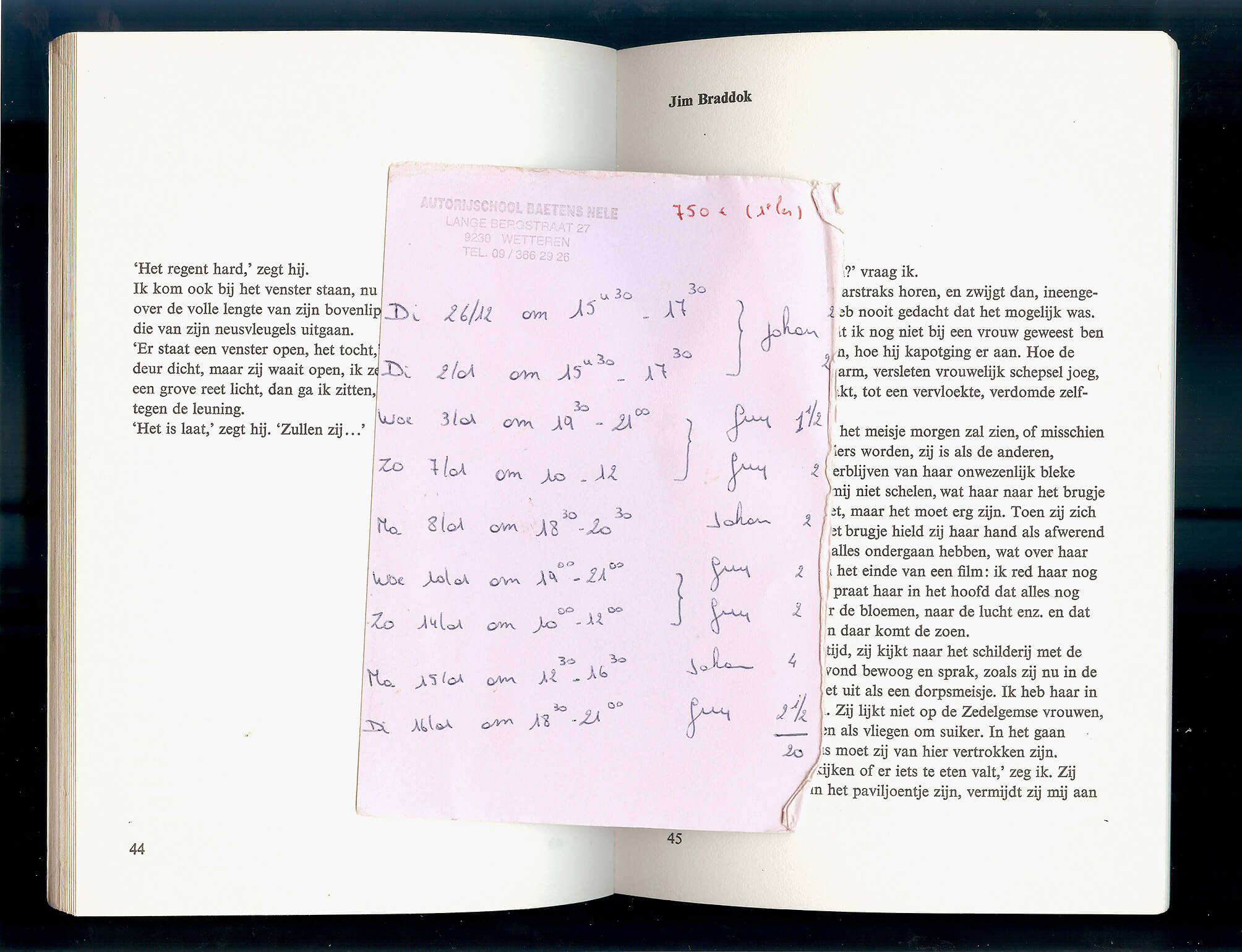

In his debut novel ‘De Metsiers’ Hugo Claus employs a multiple narrative perspective. In the copy I picked up in a thrift store, there’s a bookmarker between pages 44 and 45 where the perspective shifts from Ana to Jim Braddok. It’s pouring. The pink piece of paper lists 9 sessions at a driving school. There’s a total of 20 hours, taught alternately by Johan and Guy.

In 2000, 2006 and 2017 the twenty-sixth of December was a Tuesday. (Earlier years are improbable, since the Euro was not introduced yet.)

Claus, H. De Metsiers. Amsterdam: Uitgeverij De Bezige Bij, 1978.

On May 23rd 2021, the planet Saturn appears to be stationary among the surrounding celestial bodies in the night sky.1 This is an attempt to capture this planetary standstill.2

A telescope is set up in a pasture, near a forest edge, pointed to the south-southeast morning sky.3

The standstill is de facto inexistent. It’s the moment when Saturn’s apparent prograde motion turns to a retrograde motion. Since Earth completes its orbit in a shorter period of time than the planets outside its orbit, it periodically overtakes them, like a faster car on a multi-lane highway. When this occurs, the planet being passed will first appear to stop its eastward drift, and then drift back toward the west.

In astrology, Saturn’s retrograde movement is generally a time of karmic rebalancing. Previous bad behavior could be punished. But hard work and responsibility could also be rewarded.

This is the third instalment of De Cleene De Cleene’s Public Observatory. Thanks to Volkssterrenwacht Mira, Grimbergen.

Briet, S. Qu’est-ce que la documentation? Paris: Edit, 1951.

Gittelman, L. Paper Knowledge. Toward a Media History of Documents. Durham/London: Duke University Press, 2014.

Oxford English Dictionary Online. Accessed on 13.05.2021.

‘Saturn Retrograde May 23, 2021 – Karmic Love’, Astrology King. Accessed on 15.05.2021.

A visit to the Royal Observatory of Belgium, in Ukkel. Most of the domes are damaged and need repairing. Only a few telescopes are in use. It is difficult to find a good spot from which to film the site. When we asked the people at the Royal Meteorological Institute – the Observatory’s neighbouring institution – if we could access their building’s roof to film the observatory, the answer was ‘no’.

I (M.D.C.) remember there was a fire nearby. We couldn’t see the flames, but a tall dark plume of smoke rose above the trees lining the site. We didn’t insist any longer and ceased our attempt to access the roof, hoping we might find a good spot to film the smoke with a dome in the foreground.

Kesteloot, J. Leerboek van Cosmografie voor Middelbaar en Lager Normaal Onderwijs (derde vermeerderde uitgave). Brugge: Firma Karel Beyaert, 1948.

The road down from the top of Mount Vesuvius, at Atrio Del Cavallo. The sun sets. The last tourist bus has headed down. Then the headlights of the guardian’s car swing their way down. It must be freezing. I am holding an orange-sized piece of petrified lava, probably stemming from the 1872 or 1944 eruption. A kilometer further down the road, the old Observatory is empty. Nowadays, monitoring seismic changes is done in a research centre in the city of Naples. Their seismographic registrations can be followed online, in real time. Two headlights swirling along the slopes, underneath me, are coming upwards.

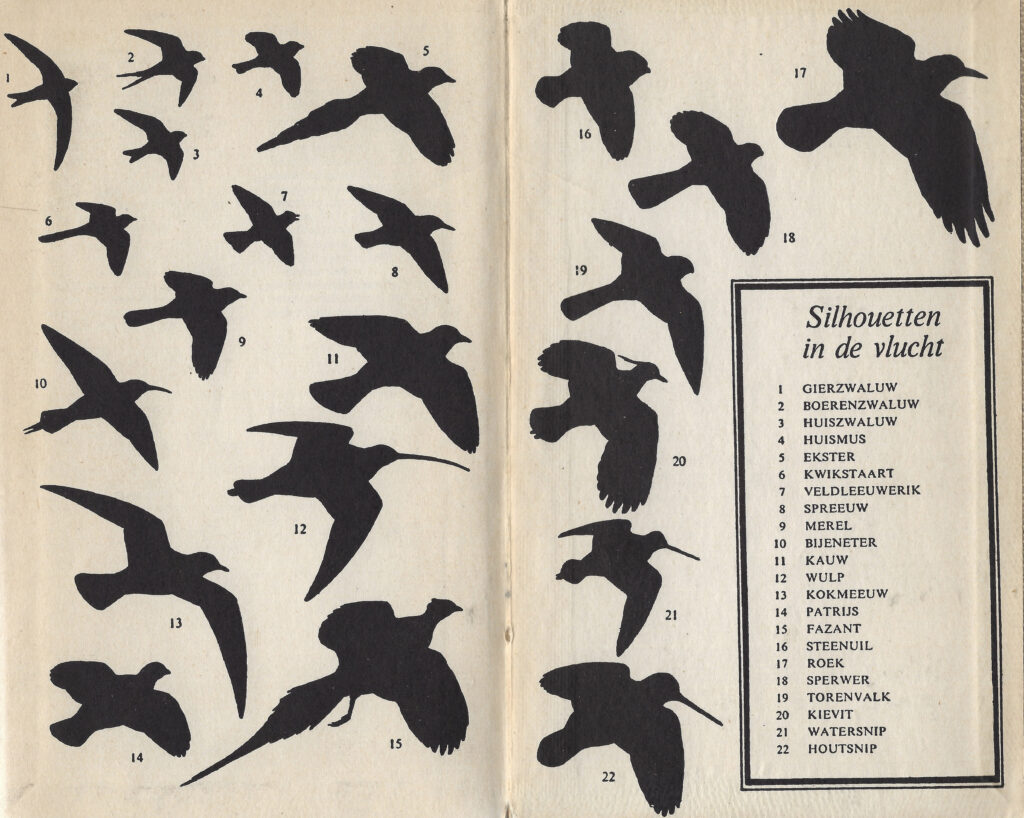

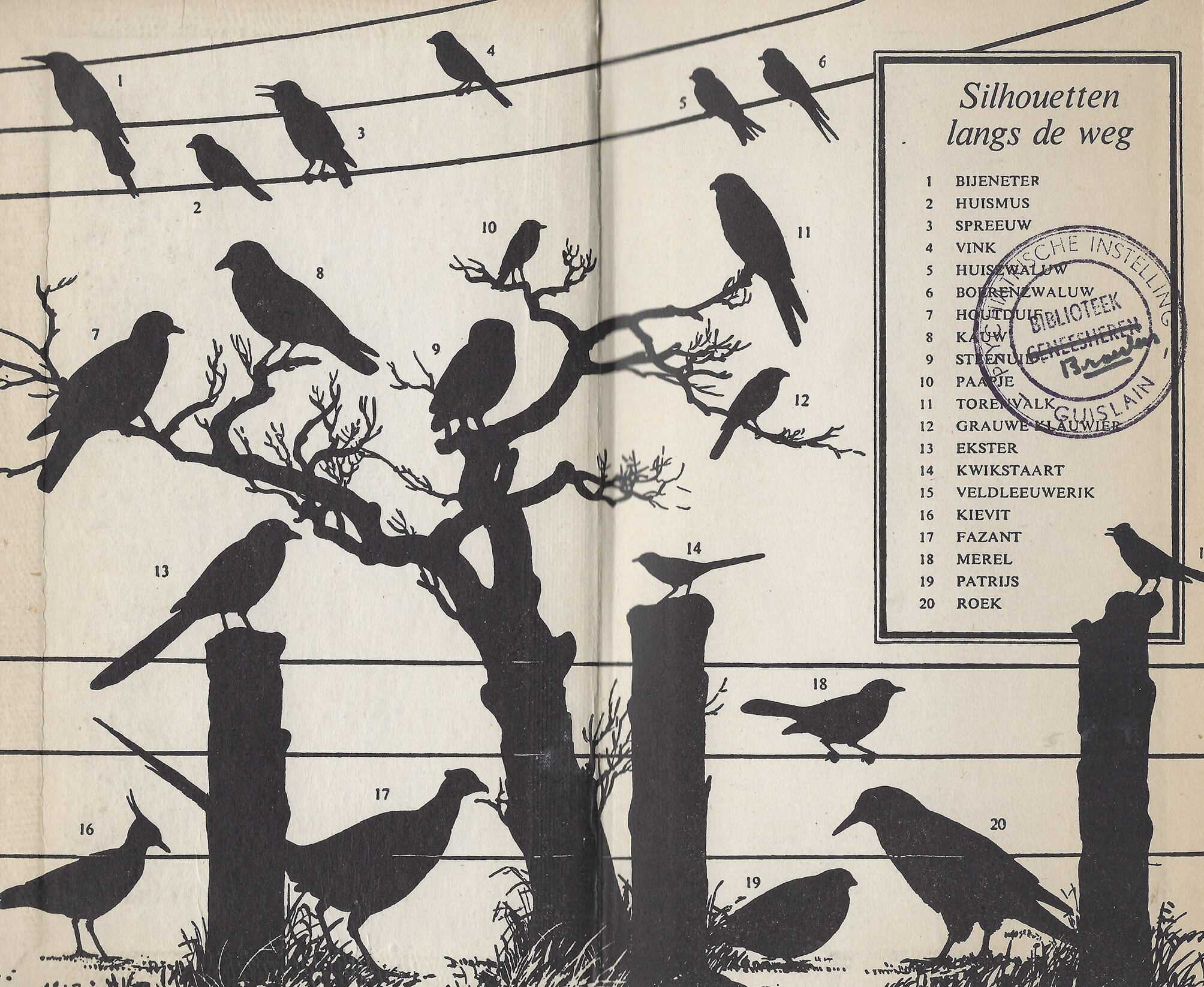

This is the spread one sees upon opening the bird field guide that once stood, as the stamp indicates, in the library of a psychiatric institution.1 It shows birds’ silhouettes, as they can be seen beside the road.

The drawing has a kind of Hitchcock feel to it.2 The birds seem to be spying on each other, as they also seem to be spying on the unsuspecting passer-by.

The composition of the scene is marvelous. The electric wires, the tree, the wire fence, the double framed list with the birds’ names, handsomely positioned in a birdless patch, at once superimposed on the telephone wires, and pushed to the background by the skylark.

Imagine seeing this scene. What are the odds: to see the silhouettes of Europe’s twenty most common species of birds in one glance, from your car’s window, as you are driving home at dusk.

Before closing the book, the last spread seems to show the birds fleeing, maybe attacking.3

The stamp indicates that, at the psychiatric institution, the book was part of the sublibrary for the Catholic Brothers of Charity. The crossed-out part indicates that there was also a separate physicians’ library, to which the book might have originally belonged.

On the web, discussions on whether Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds (1963) was shot in colour or in black and white, abound.

Peterson, R.T., Mountfort, G. & P.A.D. Hollom. Vogelgids voor alle in ons land en overig Europa voorkomende vogelsoorten (J. Kist, transl.). 3d ed. Amsterdam/Brussels: Elsevier, 1955.

A white Mercedes van inserts in front of me in a traffic jam near Antwerp. The back of the van has been altered in several ways: a latch was added to the door,1 a footstep was bolted to the bumper, a couple of tie-wraps are holding up the lights on the left side.2 Traffic is moving slow. There is no Mercedes logo.3 Some parts have been retouched with white paint that differs slightly from the rest of the bodywork,4 not unlike a tipp-ex’ed document.

Maybe the original locking mechanism no longer functions, or, perhaps, the owner wants to add a padlock to the doors at night.

Maybe a corroded screw caused the lights to come loose, or a slight collision.

Someone might have stolen it. Mercedes stars are often stolen, although mostly from the hood.

Maybe to counter corrosion, to conceal a mark someone made on the van or to cover up a fixed dent.

Legislation concerning the publication of someone else’s licence plate on the internet and the demand to blur it, is somewhat ambiguous.

In his Handboek Varende Scheepsmodellen (Handbook Sailing Ship Models) André Veenstra explains the different classes in ship model-competitions. There’s a wide variety. For static ship models the most important one is ‘truth-to-nature’. A jury compares the model to photographs of the actual ship and brings into account categories such as amount of work, degree of difficulty, scale ratio, construction execution and painting.

The most interesting class – according to Veenstra – is F 6. In this particular class, a number of participants with different boats will form a team. Together, they will perform a certain ‘act’ with a maximum duration of ten minutes. During the act, they mimic a slice of reality. Such as, for example, ‘rescuing’ and towing a ship in distress; extinguishing a fire on a tanker or oil rig, lichen and/or tow the sunken wreckage to the harbor, stage a naval battle, etc.

Page 262 shows a photograph of such a mimicked slice of reality. The caption explains: ‘Image 14.15. The Dutch demonstration in the F 6 class during the European Championship of 1975: the oil rig is set on fire by a motorboat with terrorists. The fire is extinguished and the oil rig is quickly towed to a safe harbor by tugs. The show was performed by six people and took a very creditable fourth place.’

A visit to the Royal Observatory of Belgium, in Ukkel. Most of the domes are damaged and need repairing. Only a few telescopes are in use. It is difficult to find a good spot from which to film the site. When we asked the people at the Royal Meteorological Institute – the Observatory’s neighbouring institution – if we could access their building’s roof to film the observatory, the answer was ‘no’.

I (M.D.C.) remember there was a fire nearby. We couldn’t see the flames, but a tall dark plume of smoke rose above the trees lining the site. We didn’t insist any longer and ceased our attempt to access the roof, hoping we might find a good spot to film the smoke with a dome in the foreground.

Kesteloot, J. Leerboek van Cosmografie voor Middelbaar en Lager Normaal Onderwijs (derde vermeerderde uitgave). Brugge: Firma Karel Beyaert, 1948.

Between the rhinos and the kangaroos in the Antwerp Zoo a wooden footpath curves through a grove of Sequoiadendron Giganteum trees. In the middle of this Californian forest, visitors find the giant slice of a felled tree of the same species. It was brought to the zoo in 1962 and was approximately 650 years old at the time. Eleven labels point out significant moments in history on the tree’s growth rings. They range from zoo- and zoology-related moments (for instance: ‘1901: The Okapi is described as a species’, or ‘1843: Foundation of the RZSA and opening of the Zoo’, or ‘1859: Darwin publishes The Origin of Species’, etc.), to cultural and historical milestones (‘1555: Plantijn starts publishing books in Antwerp’, or ‘1640: Rubens (baroque painter) dies’, or ‘1492: Columbus in America’). Another label points to the last growth ring and reads: ‘1962: this tree is felled and this tree disc is installed at the Zoo.’

The label pointing to the centre of the tree implies a simultaneity between the tree’s first growth year and the Battle of the Golden Spurs in 1302.

On closer inspection the slice seems to consist of two halves that were put together like a jigsaw puzzle. The resulting gap is skilfully patched with what appears to be wood from the same species – possibly even the same mammoth tree.

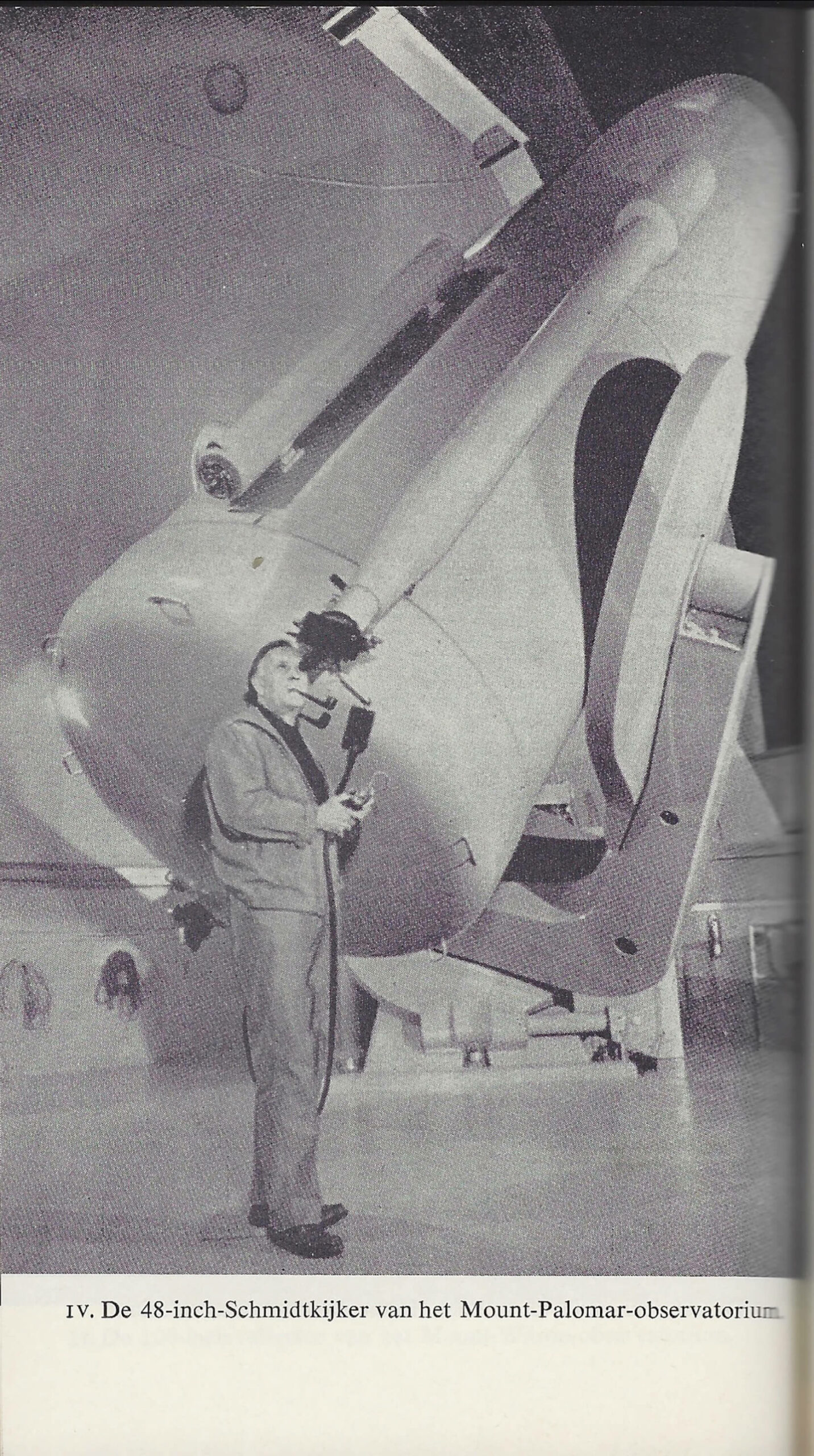

The 48-inch Oschin Schmidt, a renowned reflecting telescope at Palomar Observatory, California, was used for the Palomar Observatory Sky Survey (POSS), published in 1958, one of the largest photographic surveys of the night sky.

Based on the man’s pipe shadow’s direction, thrown onto the telescope, there is reason to believe an off-camera flash was used to make the picture.

Every two weeks, The New York Review of Books falls into my letterbox. Those are good days. Most often, I won’t get to reading it, but what I instantly do, is check the last page with ‘The Classifieds’. The people writing the (genuine, not fictitious) adverts and inquiries reappear every so often. I happily assume the position of the implied reader, as they address the presumed readers of the review. There’s a ‘charismatic, aging French rock star’ providing original songs in Franglais. There are top notch apartments in Paris for aspiring writers. There are those seeking love and astronomical peculiarities: ‘Hitch my wagon to a star – Looking for a bright sophisticated senior star gazer! CStein3981@aol.com’.

The New York Review of Books, March 11, 2021, Volume LXVIII, Number 4.

Near Avenue 61 on an artificial island close to Seef, a truck is being towed after the driver lost control over the vehicle and flipped it onto its side. A warm wind blows in from the Persian Gulf.

A police officer signals us to come closer. ‘Why are you taking pictures?’ he asks. ‘This is just an accident. You have to delete the pictures from your phone. Now.’ After checking the pictures-folder on our phones, he gets in his car, drives a few metres, stops the car and rolls down his window. ‘And don’t do it again!’ he yells. Then he drives off, raising a cloud of sand in his wake.

Photograph taken and recovered from my trash bin on 18.12.2020.

Robert Nemiroff and Jerry Bonnell’s lesser known project (R.N. and J.B. being the creators of Astronomy Picture of The Day), was making websites containing over a million of digits of square roots of irrational numbers, e.g. seven. ‘They were computed during spare time on a VAX alpha class machine over the course of a weekend. […] We believe these are the most digits ever computed for the square root of seven on or before 1 April 1994.’ Elsewhere, R.N. states: ‘They are not copyrighted and we do not think it is legally justifiable to copyright such a basic thing as the digits of a commonly used irrational number.’ If one wanted to get a copy of the 10 million digits of the square root of the number e R.N. and J.B. computed in their spare time, one can send an email to R.N. at nemiroff@grossc.gsfc.nasa.gov.

https://apod.nasa.gov/htmltest/gifcity/sqrt7.1mil

https://apod.nasa.gov/htmltest/rjn_dig.html

https://apod.nasa.gov/htmltest/rjn.html

The torn off section of roofing on the grass has part of a text carved in it: ‘UDI’ and ‘EN’ are still legible. It must have come from another roof; the one shown in the photograph has no missing sections, nor visible repairs.

The roofing that is still on the garage shows a drawing of some kind. A floorplan for a squarish building with a supporting column along each side, or the layout for a tactical explanation, perhaps.

Seven very similar and rudimentary buildings take in a trapezoid plot of land in Gilly. They are located between the school on the Rue Circulaire and the houses along the Rue de l’Abbaye. The structures are built of orange brick, concrete structural elements, whitish steel gates and roofing. Every garage has its own number, hand-painted in white on the concrete lintel above each gate. In summer the roofing gets hot and soft.

Until recently, for as long as I could remember, the packaging of Tabasco® Pepper Sauce had been unchanged. On the front of the packaging, there is a photograph of a bottle of Tabasco®, scale 1:1, against an orange background.As far as packaged goods go, this is a highly idiosyncratic and quirky example.

The background colour approximates the colour of the liquid inside the bottle, resulting in as good as no contrast. Moreover, as the image of the bottle is scale 1:1, the packaging becomes kind of unnecessary and superfluous, also because the life-sized image of the bottle is the only way information is given to the customer: there are no additional slogans, no repetition of the brand name, no props and no decor. The image of the bottle advertises the bottle. It seems to add nothing the bottle could not do by its own (like a bottle of wine does).

What makes the packaging truly stand out, however, is the fact that the image of the bottle is not positioned vertically, but is slightly askew. It seems to be the result of a design error, and has an amateur feel to it. The decision to keep it as such and not correct it up until today, is, however, a stroke of genius. The non-vertical positioning alters the relation of the image of the bottle to the bottle inside: as the box is standing on a shelf, the tilted image of the bottle undermines its representational superfluousness.

The archive of O. Clemminck, architect, was preserved in a box of croutons – by him, the historian who gave it to my father, or someone else (it contains a letter written by Clemminck’s widow asking a client to pay the bill her husband had sent). The croutons had a flavor of fine herbs and, a stamp on the box with the plans in it says, should have been consumed before April 1987.