What constitutes a ‘document’ and how does it function?

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the etymological origin is the Latin ‘documentum’, meaning ‘lesson, proof, instance, specimen’. As a verb, it is ‘to prove or support (something) by documentary evidence’, and ‘to provide with documents’. The online version of the OED includes a draft addition, whereby a document (as a noun) is ‘a collection of data in digital form that is considered a single item and typically has a unique filename by which it can be stored, retrieved, or transmitted (as a file, a spreadsheet, or a graphic)’. The current use of the noun ‘document’ is defined as ‘something written, inscribed, etc., which furnishes evidence or information upon any subject, as a manuscript, title-deed, tomb-stone, coin, picture, etc.’ (emphasis added).

Both ‘something’ and that first ‘etc.’ leave ample room for discussion. A document doubts whether it functions as something unique, or as something reproducible. A passport is a document, but a flyer equally so. Moreover, there is a circular reasoning: to document is ‘to provide with documents’. Defining (the functioning of) a document most likely involves ideas of communication, information, evidence, inscriptions, and implies notions of objectivity and neutrality – but the document is neither reducible to one of them, nor is it equal to their sum. It is hard to pinpoint it, as it disperses into and is affected by other fields: it is intrinsically tied to the history of media and to important currents in literature, photography and art; it is linked to epistemic and power structures. However ubiquitous it is, as an often tangible thing in our environment, and as a concept, a document deranges.

the-documents.org continuously gathers documents and provides them with a short textual description, explanation,

or digression, written by multiple authors. In Paper Knowledge, Lisa Gitelman paraphrases ‘documentalist’ Suzanne Briet, stating that ‘an antelope running wild would not be a document, but an antelope taken into a zoo would be one, presumably because it would then be framed – or reframed – as an example, specimen, or instance’. The gathered files are all documents – if they weren’t before publication, they now are. That is what the-documents.org, irreversibly, does. It is a zoo turning an antelope into an ‘antelope’.

As you made your way through the collection,

the-documents.org tracked the entries you viewed.

It documented your path through the website.

As such, the time spent on the-documents.org turned

into this – a new document.

This document was compiled by ____ on 03.06.2023 07:30, printed on ____ and contains 61 documents on _ pages.

(https://the-documents.org/log/03-06-2023-5360/)

the-documents.org is a project created and edited by De Cleene De Cleene; design & development by atelier Haegeman Temmerman.

the-documents.org has been online since 23.05.2021.

- De Cleene De Cleene is Michiel De Cleene and Arnout De Cleene. Together they form a research group that focusses on novel ways of approaching the everyday, by artistic means and from a cultural and critical perspective.

www.decleenedecleene.be / info@decleenedecleene.be - This project was made possible with the support of the Flemish Government and KASK & Conservatorium, the school of arts of HOGENT and Howest. It is part of the research project Documenting Objects, financed by the HOGENT Arts Research Fund.

- Briet, S. Qu’est-ce que la documentation? Paris: Edit, 1951.

- Gitelman, L. Paper Knowledge. Toward a Media History of Documents.

Durham/ London: Duke University Press, 2014. - Oxford English Dictionary Online. Accessed on 13.05.2021.

In Walter Benjamin’s The Arcades Project, Convolute Q is dedicated to the panorama. Benjamin writes: ‘Setup of the panoramas: View from a raised platform, surrounded by a balustrade, of surfaces lying round about and beneath. The painting runs along a cylindrical wall approximately a hundred meters long and twenty meters high. The principal panoramas of the great panorama painter Prévost: Paris, Toulon, Rome, Naples, Amsterdam, Tilsit, Wagram, Calais, Antwerp, London, Florence, Jerusalem, Athens. Among his pupils: Daguerre’ (Q1a, 1).

Benjamin, W. The Arcades Project (H. Eiland & K. McLaughlin, trans.). Cambridge/London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2002, p. 528.

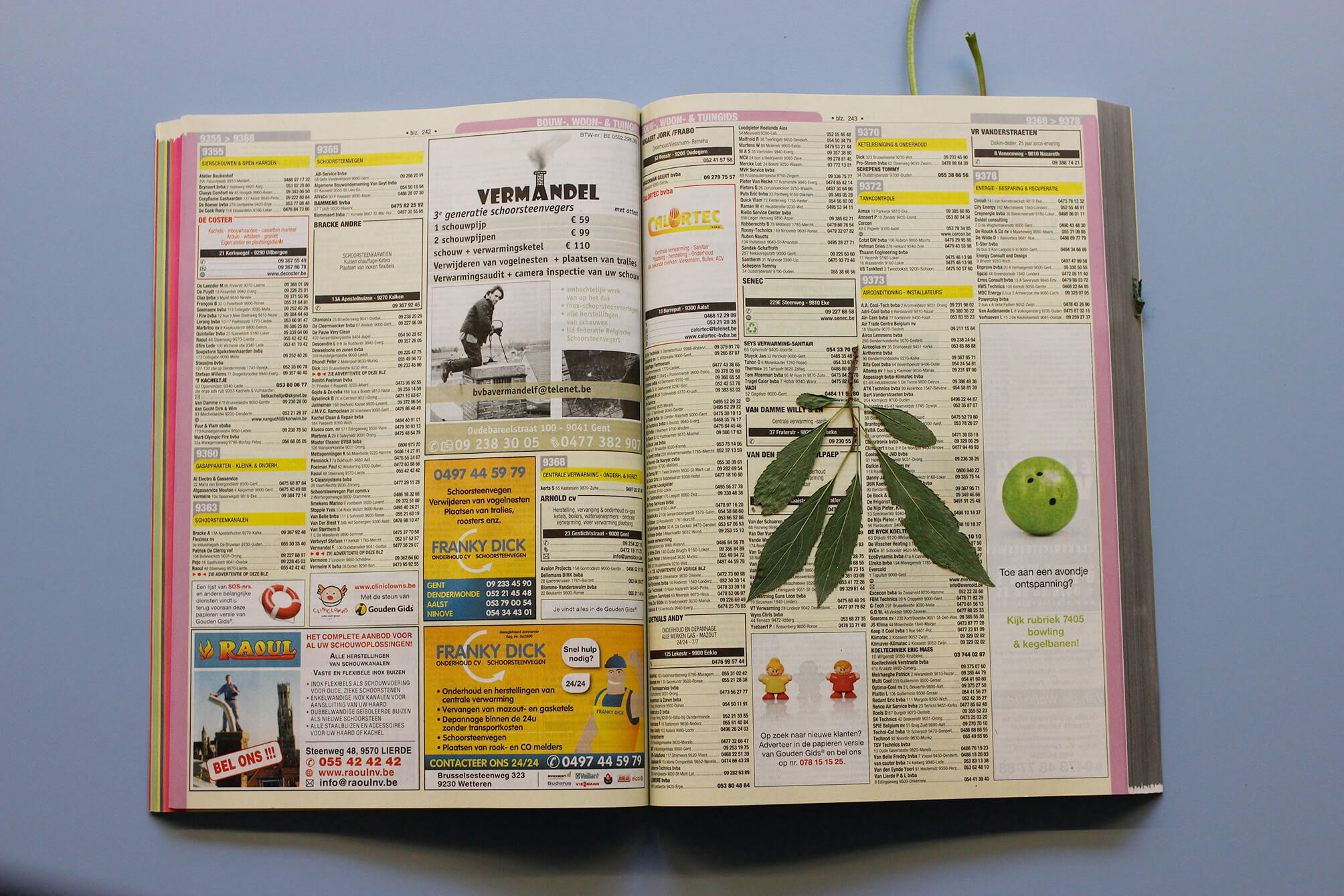

In 2020, the print versions of the Flemish telephone books ‘Gouden Gids’ and ‘Witte Gids’ (The Golden Guide and The White Guide), were published for the last time. From that year onwards, the directory could only be accessed and consulted online. The effect of the production of print telephone directories on the environment is considered to be enormous. As yearly updated, ubiquitous books, they were publications that soon turned superfluous. They led to piles of waste.

From the beginning of the 21st century on, both the print version and the online version had been available. This was a period of medium transition. During the last two decades, the print directory increasingly referred to the websites of the companies listed. To search for e.g. someone to inspect the heating installation, it was possible to find such a company’s website via the print directory, and consult the inspector’s services and price online, bypassing search engines such as Google and its complex algorithms. The telephone directory had a thematic and alphabetical order, combined with the possibility to buy additional advertising space.

It’s early spring. The pool is covered with a sheet of plastic. The deciduous trees are just leafing out. A tree stump serves as a placeholder for the diving board’s foot – it was customary to take it indoors for winter – and keeps people from kicking its threaded rods sticking up from the silex tiles that line the pool.

The upper right corner of the plastic frame is missing. It’s probably where the insect – now dead, dry and yellowish – got in. The frame was left behind in the laundry room overlooking the garden, the pool and the pool house. At the time it hadn’t been used for quite a while. Half empty, the water green.

In summer, when the wind dropped, horse-flies came. You could shake them off temporarily by swimming a few meters underwater.

According to @missbluesette, the green K-10 put up for sale by Fred from Zwolle that I came across on marktplaats.nl on 29 September 2022 is not green, but blue. The colour resembles turquoise, I explain, a colour I have always called green. No, turquoise is not green, but blue, she replies. And the texts of my Instagram posts are too long, she says, so she doesn’t read them.

Lars Kwakkenbos lives and works in Brussels and Ghent (B). He teaches at KASK & Conservatorium in Ghent, where he is currently working on the research project ‘On Instructing Photography’ (2023-2024), together with Michiel and Arnout De Cleene.

At a dental practice, the white Alligat®-powder is mixed with the right amount of water to get a mouldable dough that is pressed upon a patient’s teeth. After thirty seconds, the Alligat®-dough stiffens and takes on a rubber-like quality. At that point, still white, it must be removed from the patient’s mouth. Over the next few hours, the mould turns increasingly pink as the substance becomes less humid. Now, it can be used as a mould to create a positive master cast of the patient’s teeth.

Outside the dental practice, the powder’s possibilities remain to be fully explored.

First published as part of De Cleene De Cleene. ‘Amidst the Fire, I Was Not Burnt’, Trigger (Special issue: Uncertainty), 2. FOMU/Fw:Books, 25-30

On Mondays, before noon, I go to the supermarket with my two-year-old son. After passing the lasagnes, the loaves of bread and the fruit and vegetables, we make a short stop at the aquarium with the lobsters. Around New Year, there are two of them.

After we’ve paid for the groceries and have put them in the car, we walk into the pet shop. We look at the parrots (Jacques, Louis and Marie-José), the rabbits, the guinea pigs, the assorted caged birds and the fish and turtles. He’s very fond of the Cyphotilapia Frontosa Burundi. He calls them zebras. They hail from Lake Tanganyika, the label says. It’s the second-oldest freshwater lake, the second-largest by volume and the second-deepest. The pet shop has adorned their aquarium with a scene of ocean waste.

In an effort to avert guilt, I look for something cheap and more or less useful to buy: birdseed, a snack for the neighbour’s cat, a comb for his grandparent’s Labrador, etc.

Article 75 of the Royal Decree containing general regulations for road traffic and the use of public roads, published in Het Belgisch Staatsblad on 9 December 1975, lists the rules for longitudinal markings indicating the edge of the roadway.

According to 75.1, there are two types of markings that indicate the actual edge of the roadway: a white, continuous stripe and a yellow interrupted line. The former is mainly used to make the edge of the roadway more visible; the latter indicates that parking along it is prohibited.

In 75.2, the decree focuses on markings that indicate the imaginary edge of the roadway. Only a broad, white, continuous stripe is permitted for this purpose. The part of the public road on the other side of this line is reserved for standing still and parking, except on motorways and expressways.

https://wegcode.be/wetteksten/secties/kb/wegcode/262-art75

As the hours passed, and while clouds continuously kept us from seeing stars and planets, we started to photograph the set-up used to launch this website. To highlight the umbrella that protected the gear from the unpredictable bursts of rain, we used a flashlight: during the thirty second long exposure, it was lit for two seconds. This proved to be enough to give the whole the feel of an untampered, realistic view. Meanwhile, the website was in all likelihood streaming a grey haze, as the telescope was pointed to the fleeting clouds and gradually spinning along with the earth’s movement to keep track of the same invisible celestial bodies. As we returned to the base, planet Jupiter had become visible to the naked eye.

In another exposure of the same length, we left the flashlight on for approximately eight seconds and pointed the beam a bit lower.

In Veurne, at the bakery museum, old speculaas moulds are presented in an almost religious fashion. Looking at these wooden blocks, they appear to be the negatives to Romanesque sculptures.

How does it feel to be conserved and showcased when your nature is to be a tool? What would it mean to re-use them, to fill those empty moulds, to shape something new without altering the matrix, to project what it would be like, to try out recipes and different baking, to learn from it and enjoy the results together? What scenes are even depicted? We lost part of their meaning, we could dig further, browse the books, ask our grandparents and collectively invent whatever narrative they might hold.

Clementine Vaultier’s interests, although trained as a ceramist, are in the warm surroundings of the fire rather than the production it engenders.

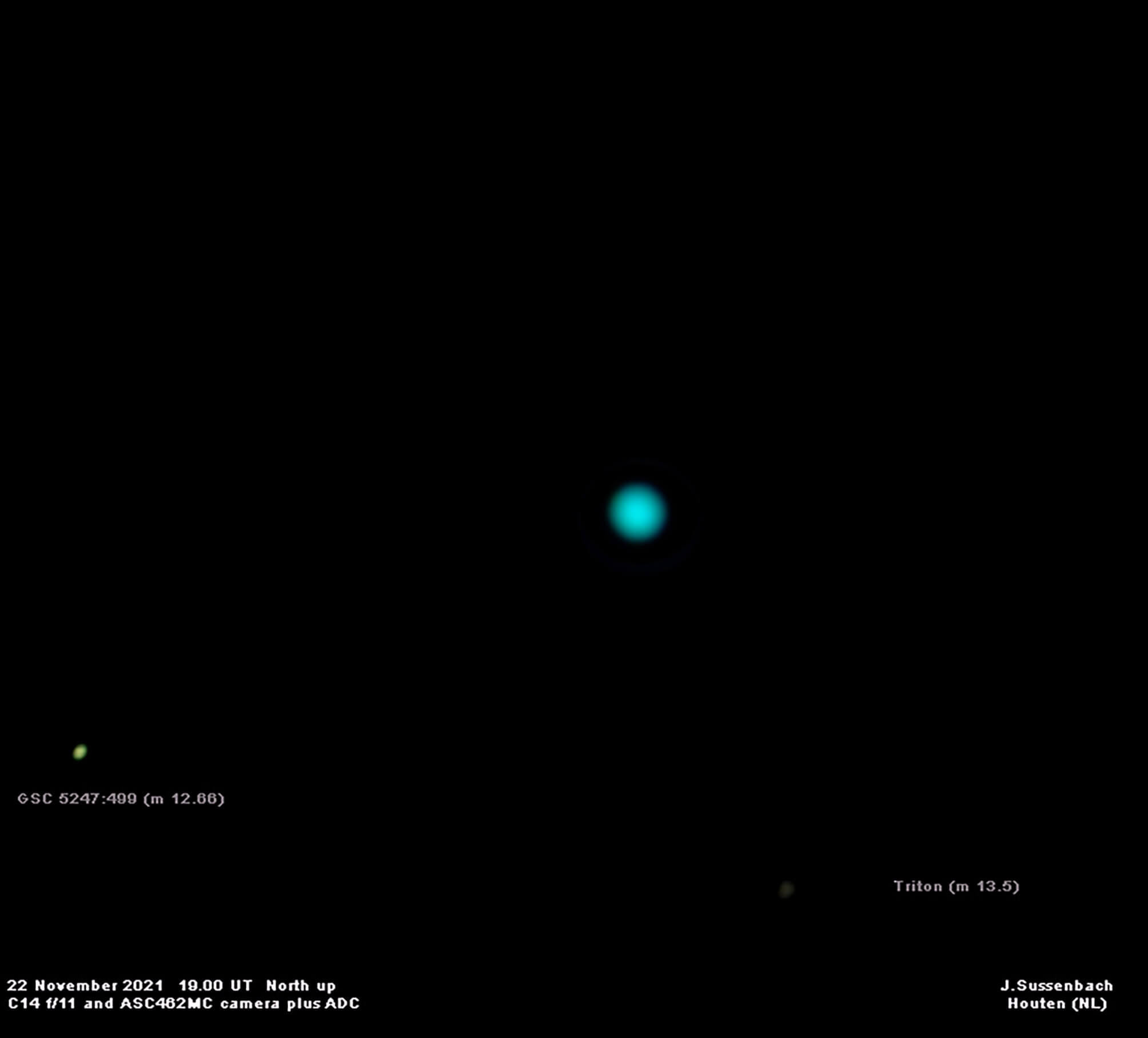

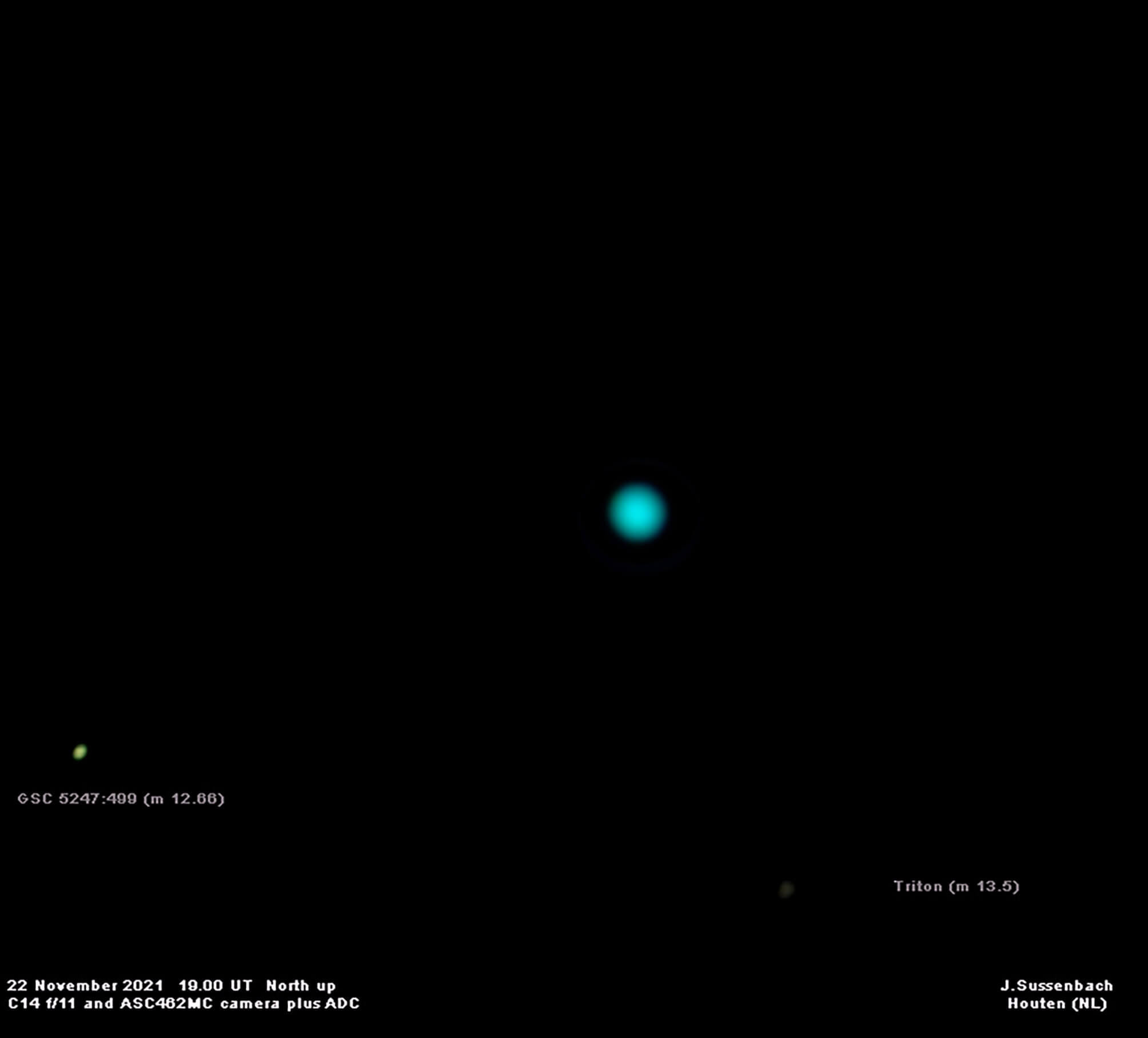

In Six Stories from the End of Representation, James Elkins writes: ‘Astrophysicists are well practised in “cleaning up” photographic plates by adjusting colour and contrast, removing images of dust, correcting aberrations, restoring lost pixels, and balancing uneven background illumination. When it comes to blur, the usual strategy is to specify what counts as “smooth” and what counts as “pointlike,” and then refine the image until it exhibits the required pointlike properties’1. Still, some astronomic images keep a certain amount of blur (although it would be technically possible to delineate them). Elkins continues: ‘blur does not need to be a matter of distance from some hypothetical optimal clarity: it can be a functional scale, independent of the viewer’s notions of clarity and even of the image itself’2.

On the night of 22 November 2021, I join John Sussenbach in his backyard while he captures Neptune.

He invites me to join him and his wife for dinner. A prayer. Soup and bread. The images he makes, he explains, are complex from a temporal point of view. The light coming from Neptune has travelled for four hours before it reaches us. Moreover, these images are not photographs of a singular moment, but stacked frames of a video-recording. In doing so, he can, to some extent, eliminate the effects of a bad ‘seeing’: the negative effect atmospheric turbulence has on the light that reaches the telescope.

A bright dot is jumping around on his laptop’s screen. ‘That’s Neptune’, he says. With his index finger he follows the dot. ‘That’s the bad seeing. That’s the unrest.’

The next day I send him the photograph I took of him standing on his ladder, dangerously placed on the edge of the tarp covering his pool. ‘Nice to see the open star cluster Pleiades in your photograph’, he replies. He attaches the image he made that night: ‘If there would have been a clear storm on Neptune, it would have shown’.

Image by John Sussenbach. 22 November 2021 19.00 UT North up

C14 f/11 and ASC462MC camera plus ADC, Houten (NL)

Elkins, J. Six Stories from the End of Representation. Images in Painting, Photography, Astronomy, Microscopy, Particle Physics, and Quantum Mechanics, 1980-2000. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2008, 59.

Ibid., 62-63.

During the night, both of us get unwell. One of us is shaking, intensely and relentlessly. The windows are open. For minutes that seem to be hours, it feels like it’s freezing. We get extra blankets. Then, it gets too hot.

One of us dreams about coccodrillos. It starts out with a single animal, like the one we saw in the National Archaeological Museum, escaping from an aquarium, and ends with lots of little ones crawling all over the place. It’s impossible to know how many have escaped.

The other dreams about seismologist Luigi Palmieri’s unfortunate assistant and his family’s quest to redeem his good name. To deprive him of the burden and guilt set upon him by Luigi Palmieri’s report of the 1872 eruption of Vesuvius, the assistant’s offspring were building a monument just below the observatory in which their great-grandfather fell asleep. The monument was permanently, and continuously, unfinished.

We both dream of hearing fireworks in Naples.

In the morning, we’re slightly alarmed that we both got sick and feverish at the same instant. It’s the middle of January, and the weather has been summerlike all week. A gentle morning breeze flies in from the Neapolitan bay while we wait for the bus to take us to the airport.

First published as part of De Cleene De Cleene. ‘Amidst the Fire, I Was Not Burnt’, Trigger (Special issue: Uncertainty), 2. FOMU/Fw:Books, 25-30

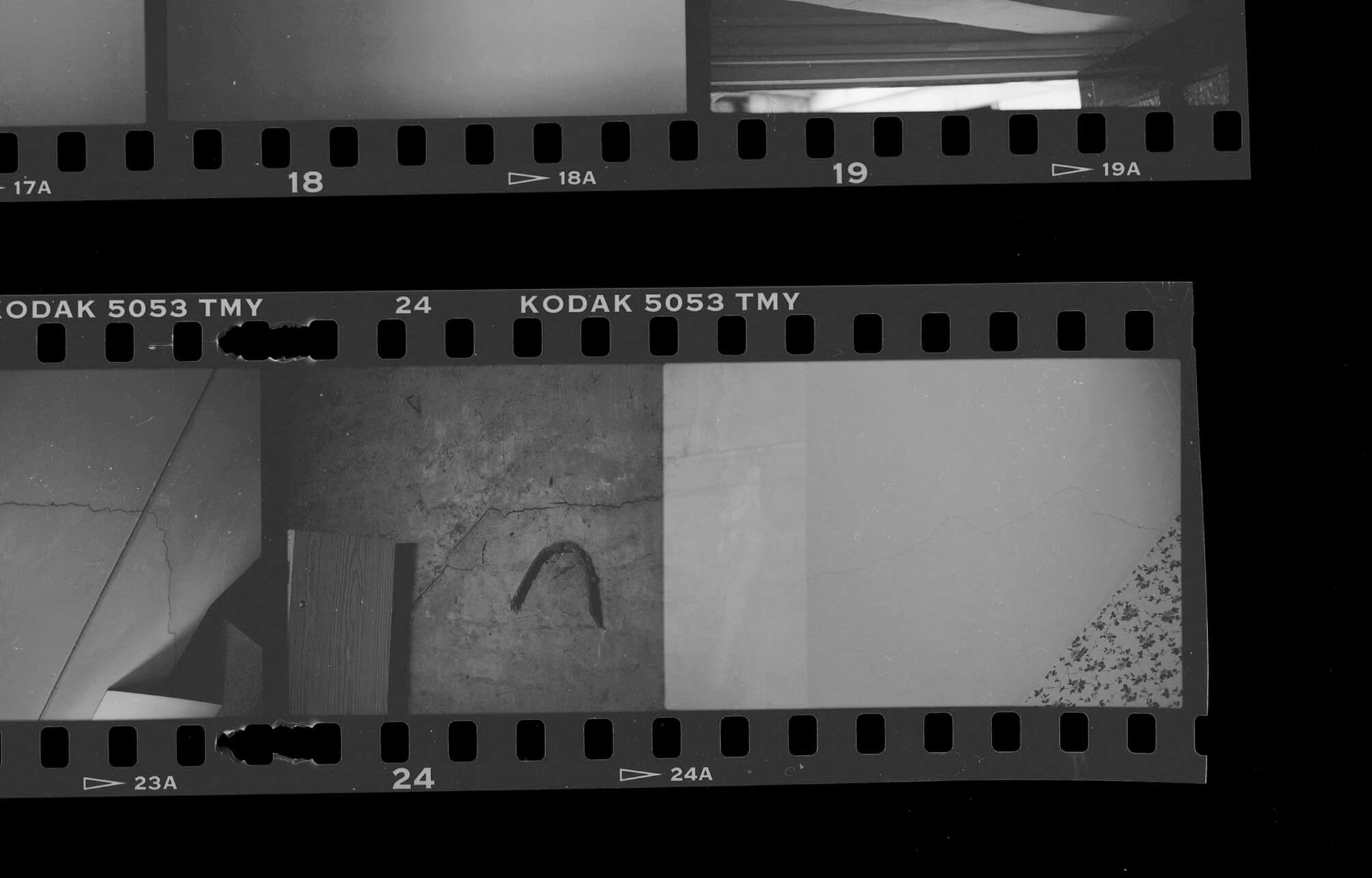

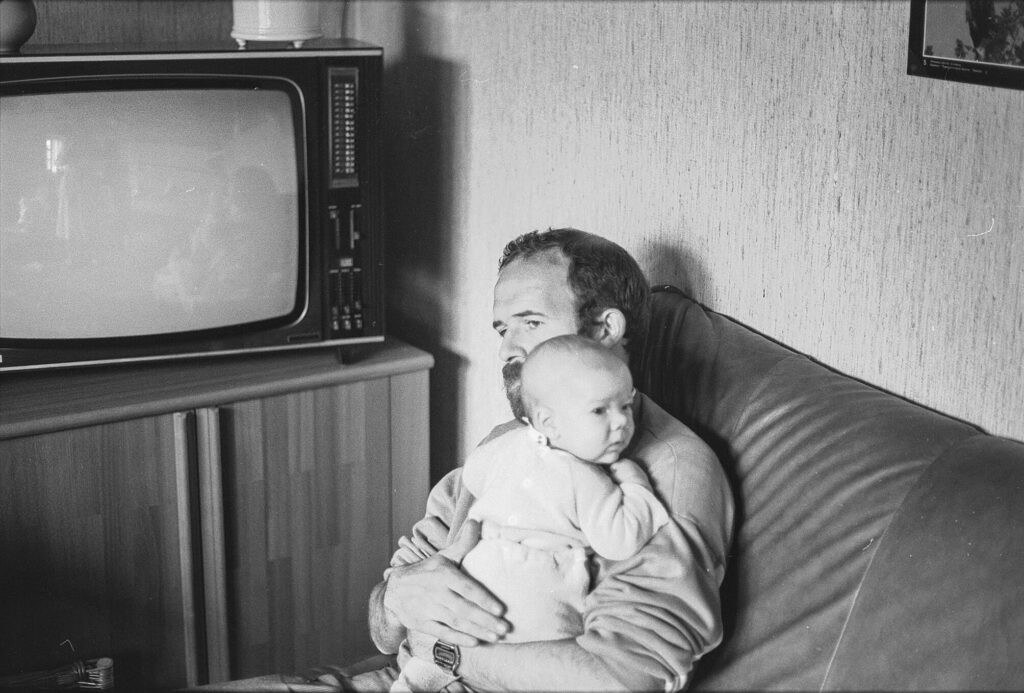

He’s wearing a digital watch. It looks like a Casio. It’s impossible to read the time, no matter whether you are studying the high-resolution scan of the negative or the negative itself, with the aid of a loupe and lightbox.

The device had a stopwatch function. When we were around eight and ten, we used to compete in trying to start and stop the stopwatch in the shortest possible interval. The smaller the gap, the closer to zero. Sometimes he would also have a try. We once managed to get it down to 00:00:00:03. Neither of us dared to press ‘reset’ and try again.

During the night, both of us get unwell. One of us is shaking, intensely and relentlessly. The windows are open. For minutes that seem to be hours, it feels like it’s freezing. We get extra blankets. Then, it gets too hot.

One of us dreams about coccodrillos. It starts out with a single animal, like the one we saw in the National Archaeological Museum, escaping from an aquarium, and ends with lots of little ones crawling all over the place. It’s impossible to know how many have escaped.

The other dreams about seismologist Luigi Palmieri’s unfortunate assistant and his family’s quest to redeem his good name. To deprive him of the burden and guilt set upon him by Luigi Palmieri’s report of the 1872 eruption of Vesuvius, the assistant’s offspring were building a monument just below the observatory in which their great-grandfather fell asleep. The monument was permanently, and continuously, unfinished.

We both dream of hearing fireworks in Naples.

In the morning, we’re slightly alarmed that we both got sick and feverish at the same instant. It’s the middle of January, and the weather has been summerlike all week. A gentle morning breeze flies in from the Neapolitan bay while we wait for the bus to take us to the airport.

First published as part of De Cleene De Cleene. ‘Amidst the Fire, I Was Not Burnt’, Trigger (Special issue: Uncertainty), 2. FOMU/Fw:Books, 25-30

The river swells and eventually overflows, causing the death of six people and extensive damage: washed away bridges, damaged homes, submerged factories, destroyed food stocks, heavily eroded roads and paths.

In Six Stories from the End of Representation, James Elkins writes: ‘Astrophysicists are well practised in “cleaning up” photographic plates by adjusting colour and contrast, removing images of dust, correcting aberrations, restoring lost pixels, and balancing uneven background illumination. When it comes to blur, the usual strategy is to specify what counts as “smooth” and what counts as “pointlike,” and then refine the image until it exhibits the required pointlike properties’1. Still, some astronomic images keep a certain amount of blur (although it would be technically possible to delineate them). Elkins continues: ‘blur does not need to be a matter of distance from some hypothetical optimal clarity: it can be a functional scale, independent of the viewer’s notions of clarity and even of the image itself’2.

On the night of 22 November 2021, I join John Sussenbach in his backyard while he captures Neptune.

He invites me to join him and his wife for dinner. A prayer. Soup and bread. The images he makes, he explains, are complex from a temporal point of view. The light coming from Neptune has travelled for four hours before it reaches us. Moreover, these images are not photographs of a singular moment, but stacked frames of a video-recording. In doing so, he can, to some extent, eliminate the effects of a bad ‘seeing’: the negative effect atmospheric turbulence has on the light that reaches the telescope.

A bright dot is jumping around on his laptop’s screen. ‘That’s Neptune’, he says. With his index finger he follows the dot. ‘That’s the bad seeing. That’s the unrest.’

The next day I send him the photograph I took of him standing on his ladder, dangerously placed on the edge of the tarp covering his pool. ‘Nice to see the open star cluster Pleiades in your photograph’, he replies. He attaches the image he made that night: ‘If there would have been a clear storm on Neptune, it would have shown’.

Image by John Sussenbach. 22 November 2021 19.00 UT North up

C14 f/11 and ASC462MC camera plus ADC, Houten (NL)

Elkins, J. Six Stories from the End of Representation. Images in Painting, Photography, Astronomy, Microscopy, Particle Physics, and Quantum Mechanics, 1980-2000. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2008, 59.

Ibid., 62-63.

On Mondays, before noon, I go to the supermarket with my two-year-old son. After passing the lasagnes, the loaves of bread and the fruit and vegetables, we make a short stop at the aquarium with the lobsters. Around New Year, there are two of them.

After we’ve paid for the groceries and have put them in the car, we walk into the pet shop. We look at the parrots (Jacques, Louis and Marie-José), the rabbits, the guinea pigs, the assorted caged birds and the fish and turtles. He’s very fond of the Cyphotilapia Frontosa Burundi. He calls them zebras. They hail from Lake Tanganyika, the label says. It’s the second-oldest freshwater lake, the second-largest by volume and the second-deepest. The pet shop has adorned their aquarium with a scene of ocean waste.

In an effort to avert guilt, I look for something cheap and more or less useful to buy: birdseed, a snack for the neighbour’s cat, a comb for his grandparent’s Labrador, etc.

The building is almost finished. One apartment is still up for sale, on the top floor. The contractor is finishing up. There’s a long list of comments and deficiencies that need to be addressed before the building can be handed over definitively to the owner. The elevator’s walls are protected by styrofoam to prevent squares, levels, measures, drills, air compressors, chairs, bird cages, etc. from making scratches on the brand new wooden panelling.

In 1932 Brassaï began taking photographs of graffiti scratched into walls of Parisian buildings. On his long walks he was often accompanied by the author Raymond Queneau, who lived in the same building but on a different floor. Brassaï published a small collection of the photographs in Minotaure, illustrating an article titled ‘Du mur des cavernes au mur d’usine’ [‘From cave wall to factory wall’].

Seven years after the devastating flood, in 1954, the building of the dam is decided upon. Between 1959 and 1963 the infrastructure is built, and the reservoir gets filled with water in 1964 to act as a buffer for sudden floods and to guarantee a flowing Thur through the highly industrialized area downstream.

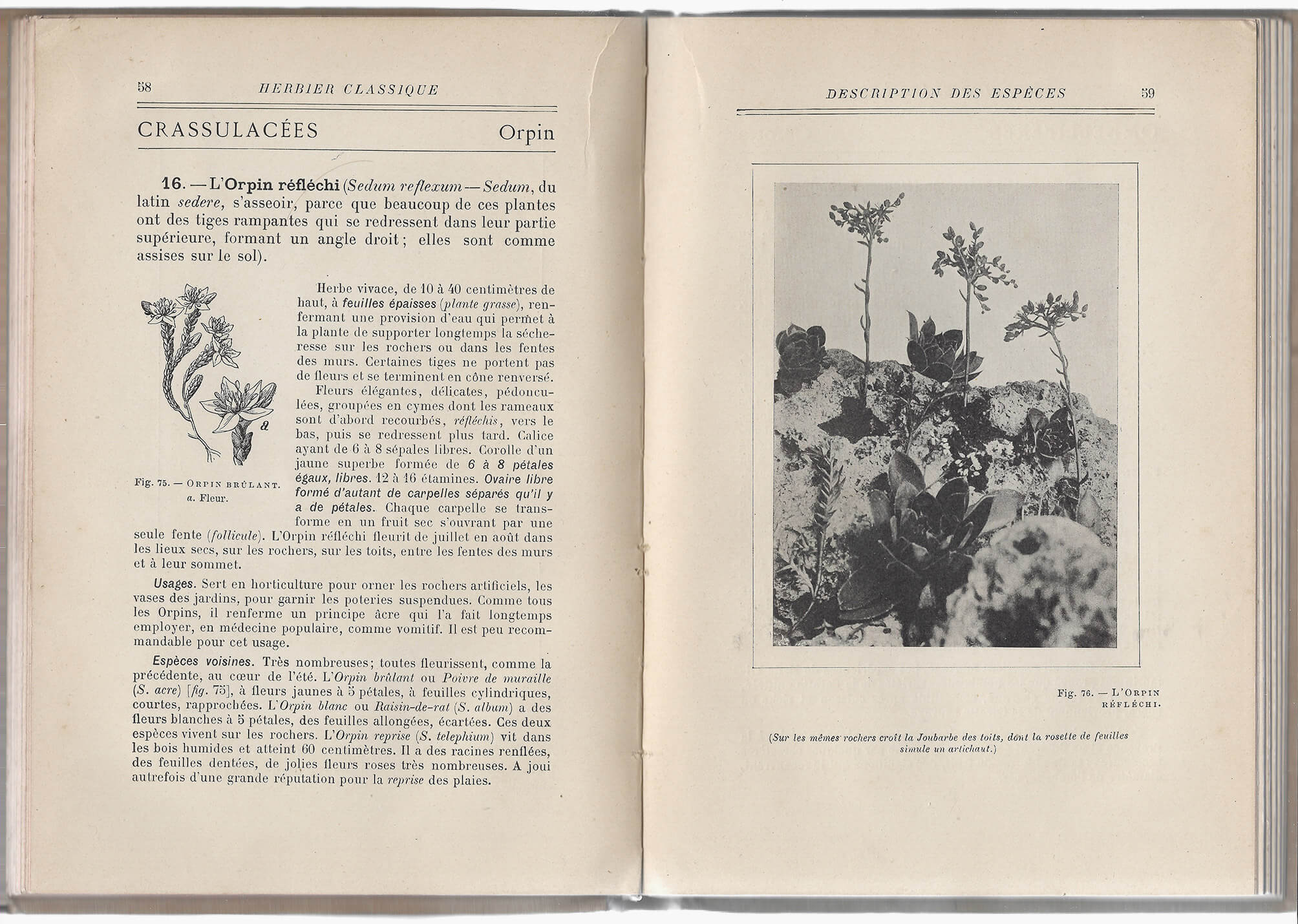

The Sedum reflexum grows on rocky soils and in crevices of walls. In L’herbier classique, it is depicted in two ways, just like the other plants in the book. This double portraiture is important, the author states in the introduction: ‘one consists of the reproductions of the photographs taken by the author of this book […]; the other, drawings made by excellent artists who observed the plants themselves, showing details photography can’t reproduce, highlighting aspects the photographs leave untouched. […] From this double representation, interesting comparisons can be made, highly enlightening from an artistic point of view, between the realistic aspect of nature’s “productions” and the interpretation thereof by the draftsman’ (5).

A detail not covered by the drawing of the sedum reflexum, is the presence of other species in the vicinity of the plant, a detail shown in the photograph and described in the caption: ‘The Common houseleek grows on the same rocks, with its rosette of leaves pretending to be an artichoke’ (59).

It snows on December 19, but the situation changes on the 22nd with the arrival of an Atlantic low-pressure area, bringing masses of hot and humid air. Thaw follows.

And then, it snows again on December 26 and 27, before the arrival of a new warm front on the same day. A significant and brutal rise in temperature ensues: at Lac Noir, at 920 m, the temperature shoots up from 0,3 °C on December 27 at 7 AM to 7,4 ° C on the 28th at 9 PM.

This stack of seaweed was offered by Henning, a farmer of the wonderful island of Laeso. This matriarchal pirate island, north of Denmark, is known for its tradition of building roofs from the seaweed growing in the surrounding salty water. Back in time, women would harvest and slowly weave the material around wooden beams from shipwrecks. This time-consuming process and technique of building shelters from what comes from the sea engaged the population in working together, building a ritual around each construction. Then those wild, yet full-of-care roofs, conserved in salt, would last for hundreds of years.

When I arrived on his land, Henning told me about how he restores those old beauties, weaving fresh seaweed around old beams and pressing the collected old material into insulation panels for new buildings. We talked about the clay of his land and how seaweed can become a material for ceramics in the process of making glazes.

Clementine Vaultier’s interests, although trained as a ceramist, are in the warm surroundings of the fire rather than the production it engenders.

Our one year old’s favourite toy he’s not supposed to play with is the HP Officejet Pro L7590 All-in-one in my office. I have given up on forbidding him to play with it. We have a new game: he brings me one of his other toys, we put it on the flatbed, close the lid – as far as possible –, press the button ‘START COPY – COLOR’ and wait for the print to come out of the machine. When we place the original onto the copy, he laughs. So far we have copied his blue pacifier, his planet-earth-bouncy-ball and his rattling crocodile.

Most mornings I eat three slices of bread. I stack them. Between the highest slice and the one in the middle I put a slice of cheese (young Gouda). I put the whole in the microwave1 for 1 minute and 50 seconds. The result is what I like to call a smelteram2.

On the morning of my thirty-second birthday the plate broke in half during heating.

A contraction of smelten (Dutch for melting) and boterham (Dutch for a slice of bread).

Coming back from holidays, we were waiting for the ferry to take us from Ramsgate to Ostend. We were well on time. As the ship entered the harbour, I asked my parents if I could take a photograph. It’s the first photograph I recall taking. I remember my dad telling me to wait long enough for the ship to get closer. I didn’t. I only got one try.1

It took a while before the film was developed. I couldn’t stop imagining what the photograph would look like: some picturesque waves in the foreground, the shining white ship, the red and blue text on the side, and a cloud filled sky.

Following every holiday, when we got home, the garden and our house would be photographed with the remaining exposures on the roll of film in the camera.

The Bahrain Formula 1 Grand Prix takes place every year since the track’s inauguration in 2004 – except for 2011 when the race was cancelled due to protests in the wake of the Arab Spring. To prevent sand from covering the track and entering the air-ducts and engines, the sand near the track is sprayed with an adhesive to keep it from blowing around.

The cloud of sand in the picture (made near Avenue 61 on an artificial island close to Seef) was made by kicking it into the frame while M.R. and M.D.C. had to stop and wait for a truck that was being towed after the driver lost control over the vehicle and flipped it onto its side. Days earlier M.D.C. had tried to make a photograph of the F1-track, but couldn’t get close enough to make a decent picture.

December, 1947. Rapid snowmelt coincides with torrential precipitation. At the bottom of the Thur valley, in Wildenstein, the water gathers.

The planet Uranus should have followed a course as predicted by Newton’s laws. It didn’t. There were ‘residuals’, the 19th-century observers said: irregular data, which had to be interpreted as Uranus deviating from the projected trajectory. They could think of three possibilities. A) The planet Uranus was too far away from the Sun, which might render the Law of Gravitation invalid. B) The observations were incorrect. C) There was another planet, still further and yet unknown, with its own gravitational field and pull, causing Uranus to deviate from its course.

Following hypothesis C, astronomers predicted the position of a planet with a gravitational field, influencing Uranus, by means of mathematical calculations. Telescopes were directed to that calculated spot. There was a luminous point, with a touch of bright azure blue.

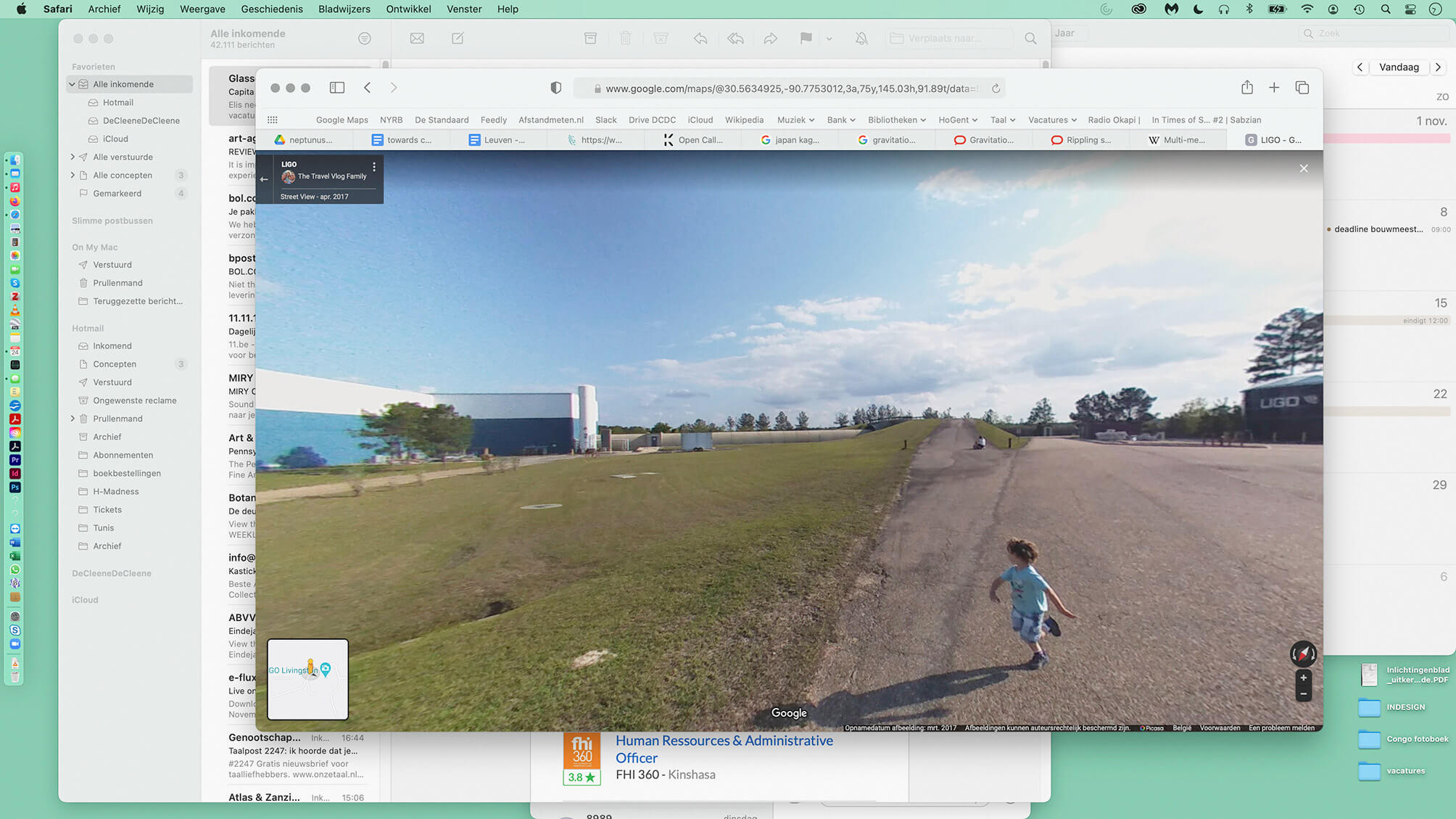

To detect gravitational waves, physicists built enormous research centers, amongst others at Livingston, Louisiana. The facility mainly consists of two tunnels in an L-shape. Mirrors inside provide data. Disturbances from gravitational waves are miniscule. To prevent interference from outside, such as vibrations caused by people passing in the neighbourhood, the mirrors have to be detached from the earth. They ‘float’, suspended by glass fibers in a pendulum-like construction. As I was watching my screen, a courier was on his way to deliver a book (Noel-Todd, J. The Penguin Book of the Prose Poem: From Baudelaire to Anne Carson. London: Penguin, 2019).

A seminar on spectroscopy: how, by splitting light into different, separate rays, it becomes possible to deduct the chemical composition of stars and planets far beyond our reach, as those elements have an effect on the light that reaches the spectroscope. Beautiful graphs presenting colour in schemes of black and white. From the moment the course gets into the physics of light, my mind wanders off. What approaches the observer turns blue, what elongates itself becomes red. The teacher’s leather shoes squeak as he goes back and forth between his self-made spectroscope and the desk. Redshift. Blueshift.

We meet him a couple of weeks later on the rooftop of a university building. He opens one of the half-domes. The sound of the mechanics is as obtuse as the shape it alters. A command on the computer based on coordinates: above our heads, the telescope slews slowly, only to halt at an apparently indistinct black region. From within the dome, we send ourselves an email with the photographs that we took of Neptune.

University classes will start in a couple of weeks. The city air is crisp. The roundabout below is strangely calm. On the horizon, the canopy of a southern forest delineates the sodium-lit sky.

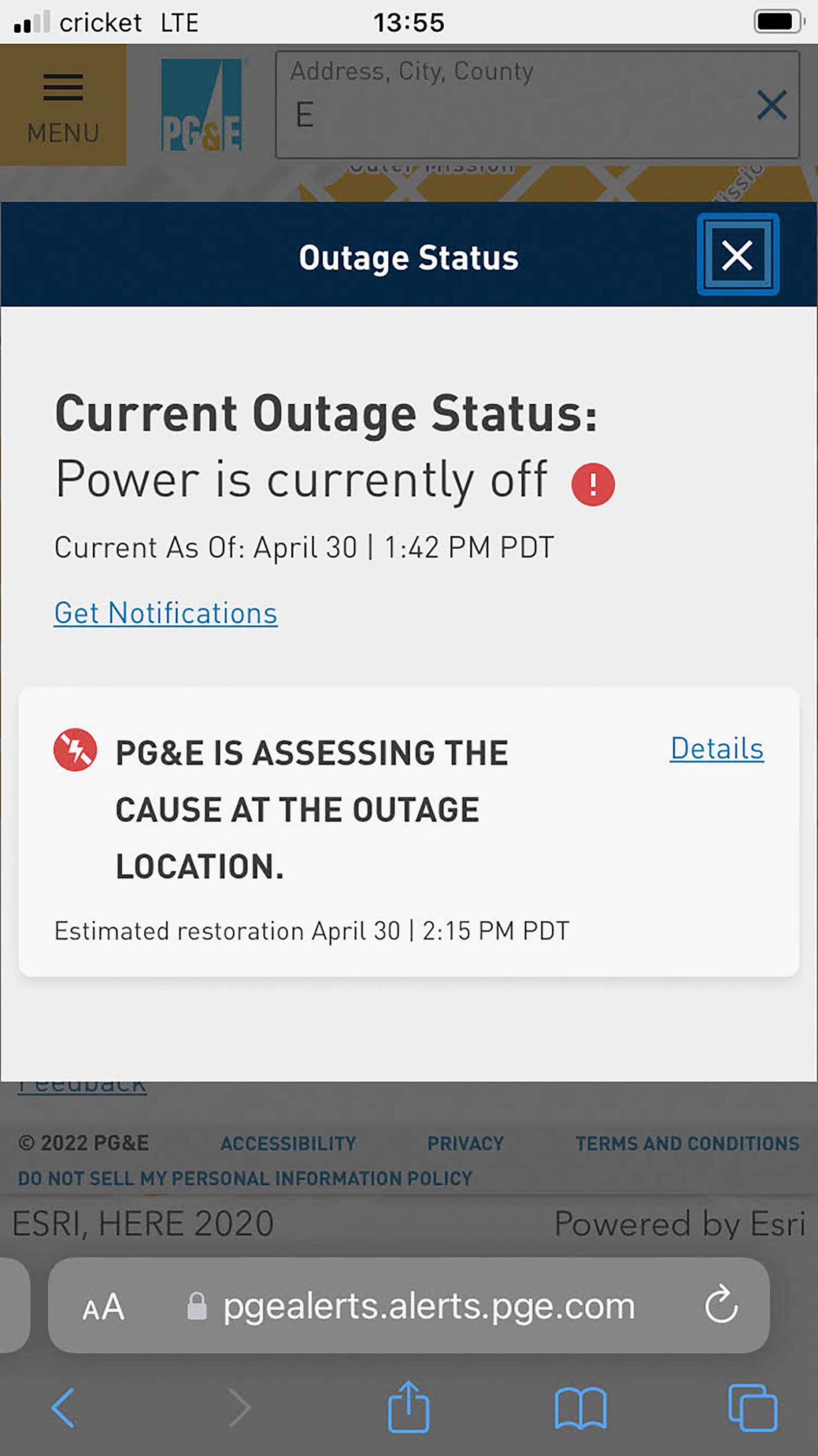

On a windy morning in April, I was on a video call with a friend, curator Maziar Afrassiabi. He listened patiently from Rotterdam as I labored over a direction for my research. It concerned a device I installed in his art space, Rib, six months prior, that monitored blackouts across California by scraping real-time data from utility companies. When a county experienced a significant blackout, it would cut Rib’s electricity in kind—causing Rib to inherit and adapt to conditions that shape Californian infrastructure. During its operation, I’d been researching the grid—learning what it is, why it fails, and how communities respond when it does.

We took a short break. Maziar, with tired eyes, stepped away for a smoke. While waiting, I watched the power lines outside my window sway limply in the breeze. In spite of its apparent lifelessness, I’ve always thought of electricity as a psychological force. My mind wandered through a cursory model of the grid, idiosyncratically cloudy and detailed.

Energy simultaneously generated and used, cascading infrastructural operations in a blink. Outlying stations burning, vaporizing, absorbing fuel, spinning vast electromagnetic turbines. Oscillating current. Neighboring transformers boosting volts to kilovolts, compensating for lost energy coursing through long-distance transmission supported by pylons peppered across Menlo Park.

Current flows into enclosed substations. Transformers, insulators, resembling a kind of industrial Watts Towers—though uninhabitable and anonymous by comparison—step voltages back down to levels safe enough for wires traversing the city. They branch out through streets via buried cables or, like the lines outside my window, are strung atop Douglas fir utility poles at roughly 30-meter intervals…curious vestigial markers. I’d read somewhere they were provisionally pitched when Samuel Morse found that telegraph signals wouldn’t transmit through the earth.

Each pole divides vertically into distinct zones, spaced apart for safety. Treacherous high-voltage wires from substations pass along the top, while safer signals—cable internet and landlines—hang nearest to the ground. The high-voltage wires enter through a barrel-shaped pole-mounted transformer. Within, submerged in oil, two tightly wound copper coils magnetically harmonize, delivering 240 and 120 volts to three exiting wires, each connected to the electrical meter attached to the building…

A blackout in my neighborhood cut my thoughts and the meeting short. The sudden silence in my apartment indicated Maziar was also in the dark. I received a text message from him and the utility company.

Mathew Kneebone is an artist based in San Francisco. His interdisciplinary practices takes different forms, all in relation to an interest in electricity and technology. He teaches studio and thesis writing at California College of the Arts.

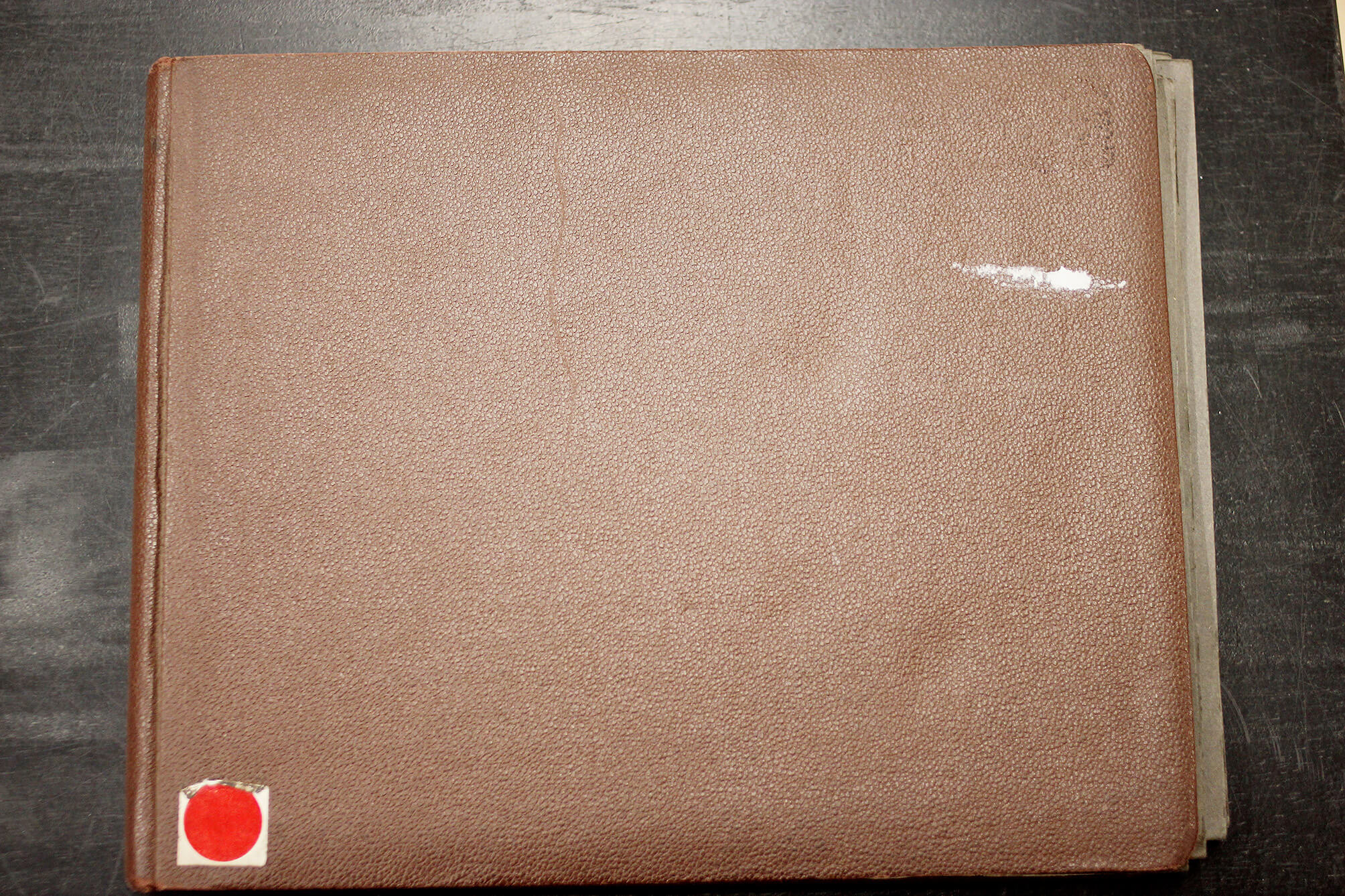

At the State Archive in Kortrijk, I am leafing through a 1955 photo album of the construction of the provisional church in Lokeren by the famous furniture company Kunstwerkstede De Coene. Gigantic wooden, prefabricated beams structure the building. It is cold. An old man in a grey suit shuffles between the racks to look up the date of birth of his great great grandmother. Snow covers the unfinished provisional roof. A bus passes, I reckon, through the pouring rain.

On 29 September 2022, I find a picture of a new Sparta K-10 on the website of cyclonewebshop.be. The bike is matt black and has a chaincase and a nice luggage rack at the front. The typical loop at the back is less noticeable in this photo. This is partly due to the colour of the bike.

Lars Kwakkenbos lives and works in Brussels and Ghent (B). He teaches at KASK & Conservatorium in Ghent, where he is currently working on the research project ‘On Instructing Photography’ (2023-2024), together with Michiel and Arnout De Cleene.

At the copyshop, on a shelf above photocopier 8, the lid of a box of paper serves as the container for ‘forgotten originals’.1

The book being copied: Didi-Huberman, G. La ressemblance par contact. Archéologie, anachronisme et modernité de l’empreinte. Paris: Les Editions de Minuit, 2008.

A sheet of brushed aluminium serves as the base for a monochromatic print showing a circular floor plan and seven photographs. The nearby Prosopis cineraria, known as the ‘Tree of Life’, is a well-known tourist attraction in the Arabian Desert near Jebel Dukhan. The plaque shows how the recently constructed concrete structure, circling the four hundred year old tree, allows the visitors to see and photograph the landmark in new and – because of the tree’s decentralized position – surprising ways. In summer the temperature can rise well over 40°C. The different expansion rates of the aluminium and its imprint cause the latter to crack.

The Cryptolaemus montrouzieri is commonly known as the mealybug destroyer. This species of ladybird gets its nickname from its capacity to battle mealybugs in plantations and greenhouses.

The website waarnemingen.be that gathers observations of plants and animals in Belgium lists multiple observations in the wild of the Cryptolaemus montrouzieri. The website explains that ‘in (northern) Europe, the species is widely traded and used in greenhouses and will regularly escape from them. But this ladybird cannot survive our winters (yet?). Sightings within the Benelux must therefore be entered into the register as “escape”. However, the species is already established in the Mediterranean area.’ (our translation)

The larvae have a waxy covering that makes them look like the mealybugs they prey upon, allowing them to avoid being correctly identified by the ones they are about to devour.

In an attempt to get rid of the mealybugs on my plants, I ordered 25 adult ladybirds. They were dead on arrival.

https://waarnemingen.be/species/600135/

https://waarnemingen.be/observation/244840499/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aggressive_mimicry

A block of concrete. Fissures are showing and rebar is sticking out from all sides. If it were still straight, the block would measure approximately 130 x 15 x 40cm.

It is lying by the side of the road, a few hundred meters from a construction site. It appears to be shaped by impact. Maybe the block plummeted to the ground from a great height. Perhaps, something heavy hit it. For all one knows, it served as a column and was exposed to an unforeseen amount of pressure, causing it to buckle.

According to Eyal Weizman ‘[a]rchitecture emerges as a documentary form, not because photographs of it circulate in the public domain but rather because it performs variations on the following three things: it registers the effect of force fields, it contains or stores these forces in material deformations, and, with the help of other mediating technologies and the forum, it transmits this information further.’1

Weizman, E. ‘Introduction’, in: Forensic Architecture. Forensis. The Architecture of Public Truth. London/Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2014.

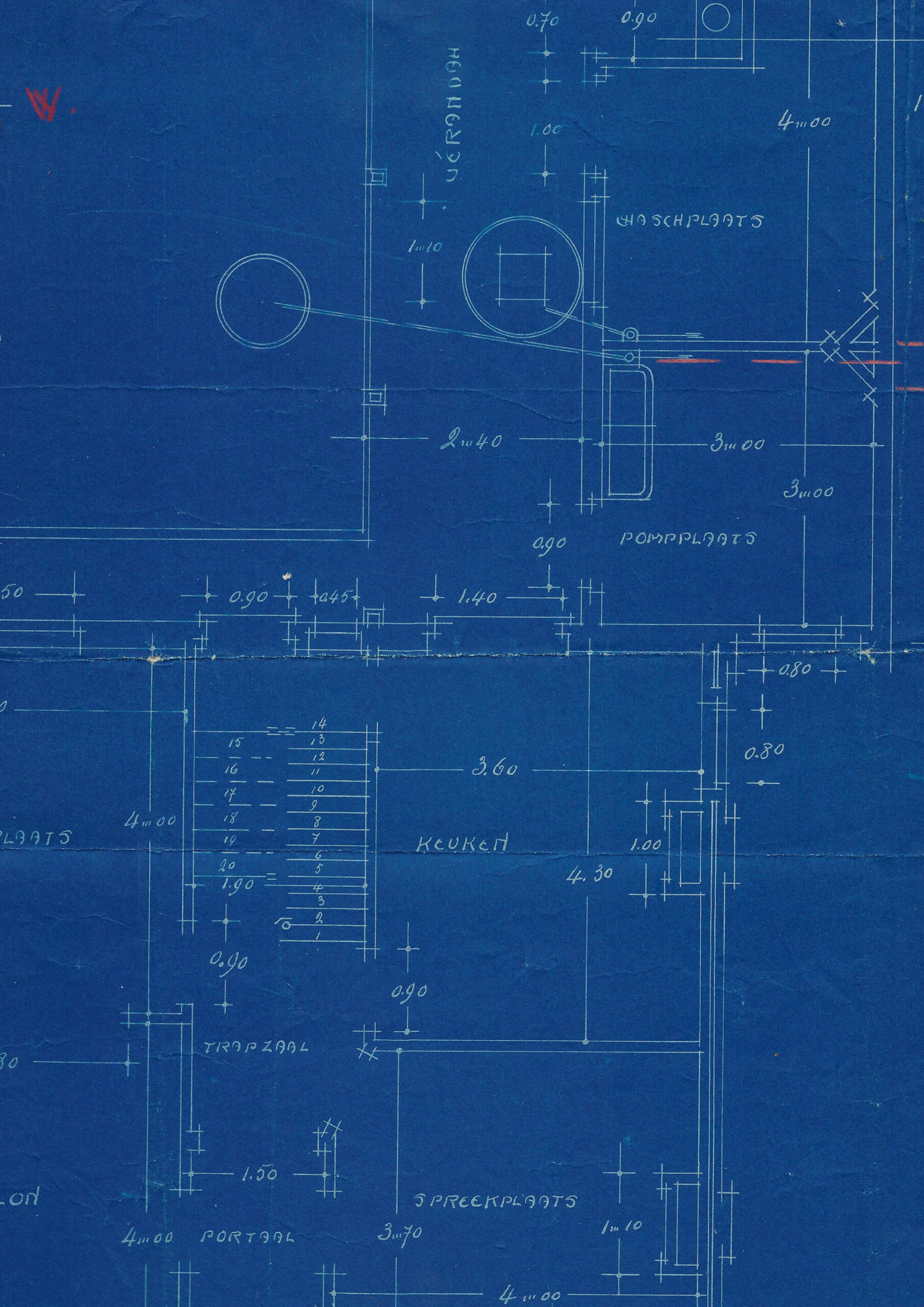

In the archive of the architect O. Clemminck, there is a piece of a plan of a building in a suburb in Gent. It presents the ground floor. There is a kitchen, a salon, an eating place, a meeting place. The missing part would have stated the exact address, the name, and maybe the profession of the owners. The plan of the first floor might have given an indication of the number of (anticipated) family members, based on the number and size of sleeping rooms.

At the southern edge of (the plan of) the lot, O. Clemminck has drawn a laundry room that gives out to a vérandah. The spelling of the Dutch word – nowadays written as veranda – is remarkable, as is its etymology, which is unclear and a matter of debate among scholars. The word might have Portuguese (varanda: railing) and Catalan roots (baranda: barrier), maybe also origins in the Lithuanian Žemaitan dialect (varanda: loop plaited from flexible wings) and might also be traced back to a Sanskrit root (varandaka: rampart separating two fighting elephants).

The vérandah O. Clemminck proposes is 2,40 meters by, at least, 2,80 meters.

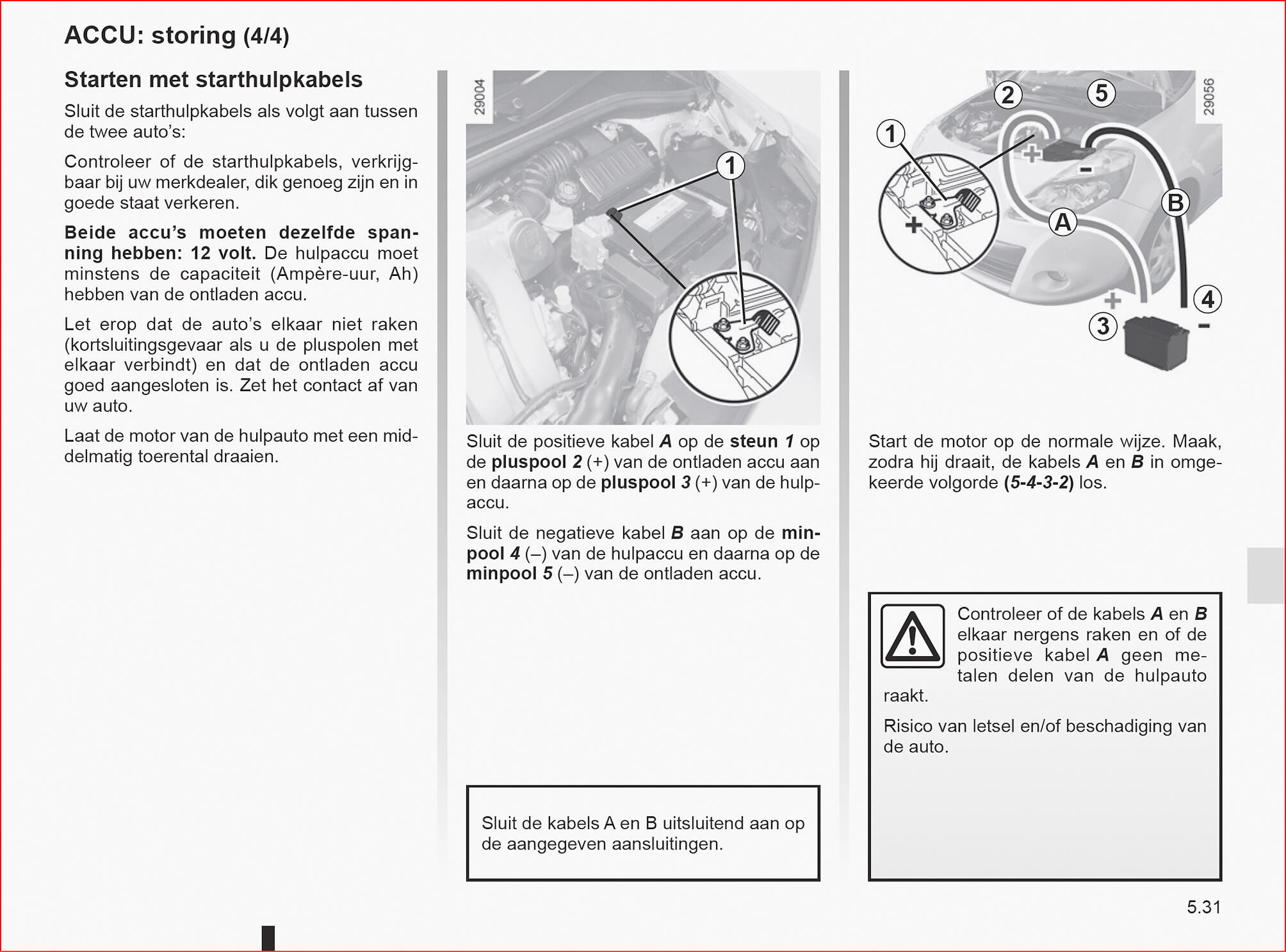

Due to strict regulations during the COVID-19-pandemic, the yearly vehicle inspection had to be scheduled by appointment. Getting ready to drive to the DMV, the car wouldn’t start. It had rained heavily, the preceding days. The day before the DMV-appointment, water had come running into the car on pushing the pedals. My socks were wet.

I called the DMV to say I needed to cancel the appointment and make a new one (but that the car, besides not being able to drive, was perfectly fine, vehicle-inspection-wise).

Later that day, we got the engine up and running again, using jumper cables and a second car, so we would be able to drive to meet the midwife the next day.

Renault Clio. Instructieboekje. 2012. PDF-file

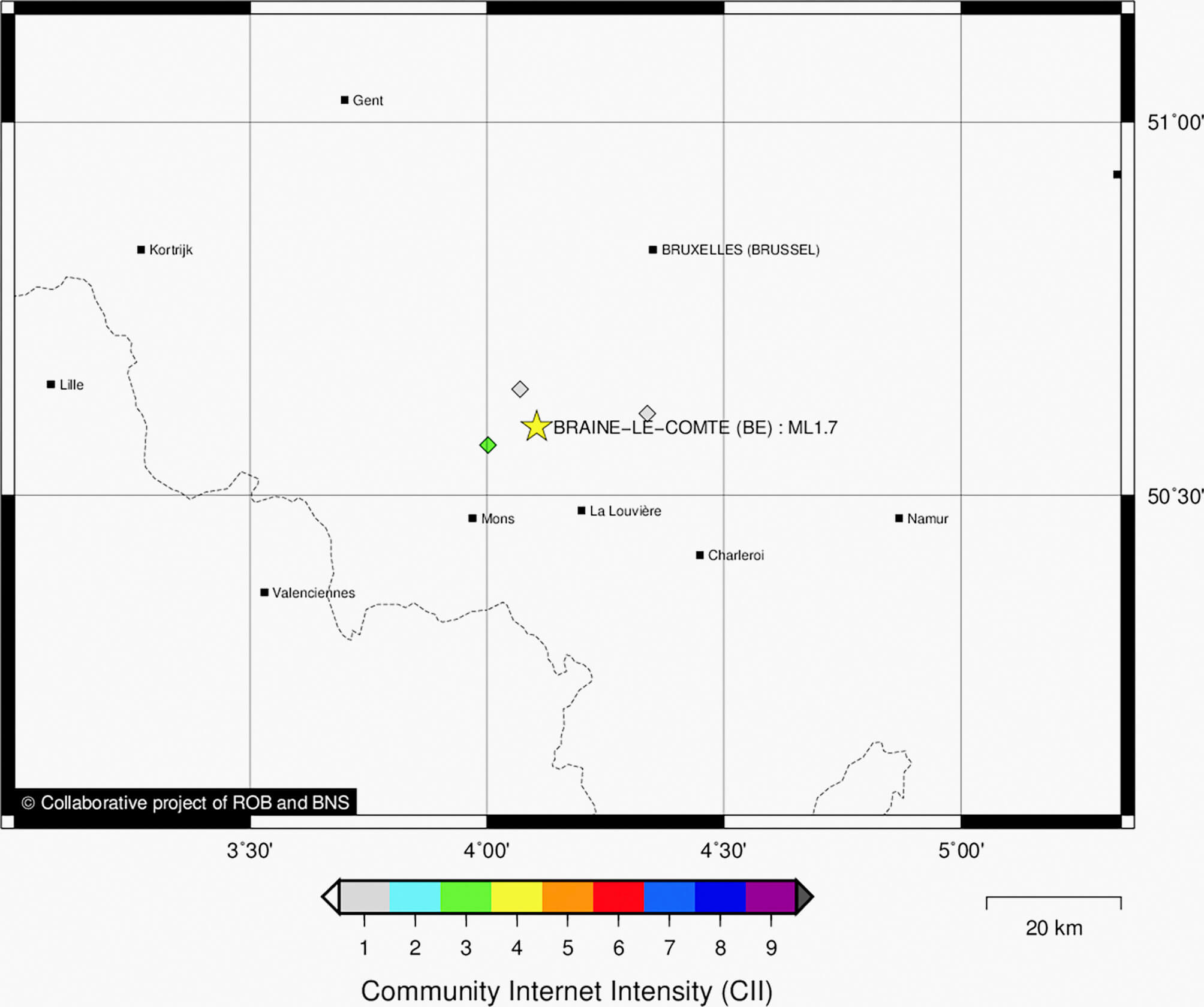

On May 6th 2020, 14h06 and 31 seconds, the Belgian Seismological Institute records an earthquake with a 1,7 magnitude in the region of Braine-Le-Compte. Three reactions from people in the neighbourhood, filed by the Institute, confirm the official seismological recordings. The Institute’s website classifies the earthquake as a ‘quarry blast’.

http://seismologie.be/nl/seismologie/aardbevingen-in-belgie/en130qj1o

Depending on the language one chooses, the Wikipedia entry for ‘document’ shows a different picture. The French-language page shows what appears to be a Slovenian thesis written in 1984. The caption states it is a ‘book of Czechoslovak computer science author Květoslav Šoustal about computer networks’. The image was uploaded by Kelovy, a Slovakian mushroom-picker.

The anonymous hand rests on a lemon-yellow tablecloth, on which a yellow book and a blue binded file lie. The top left corner is the most intriguing, however: the tablecloth seems to be draped over a lemon, alongside a drinking glass. The cloth, however, does not get shaped by the lemon. Nor does the shadow-side of the lemon coincide with the shadow the other documents throw on the tablecloth. A closer look seems to indicate that the lemon is in fact an image of a lemon, printed on a plastic napkin.

The Russian wikipedia shows the image of a lease agreement. The German wikipedia for ‘document’ is text only.

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Document#/media/Fichier:KVETOSLAV_SOUSTAL_BOOK.JPG, created October 3, 2006 / original in original: paper, 1984

The river swells and eventually overflows, causing the death of six people and extensive damage: washed away bridges, damaged homes, submerged factories, destroyed food stocks, heavily eroded roads and paths.

A 250 meter walk away from the seaside. A sign states in Dutch and French:

‘!!! NO PARKING !!!

Wrongly parked cars will be chained and only released upon payment of a € 40 parking fee’

The 40 EUR parking fee the sign threatens to charge is communicated by a relatively new sticker stuck on an older sign. Underneath the three black characters (€, 4 and 0) on a white background, there’s a relief: 7 characters declaring a parking fee of 1500 BEF.

1500 BEF equals 37,18 EUR1. In changing currency, the fee increased by 7,58%.

The Belgian franc was the currency of the Kingdom of Belgium from 1832 until 2002 when the Euro was introduced. 1 EUR is worth 40,3399 BEF.

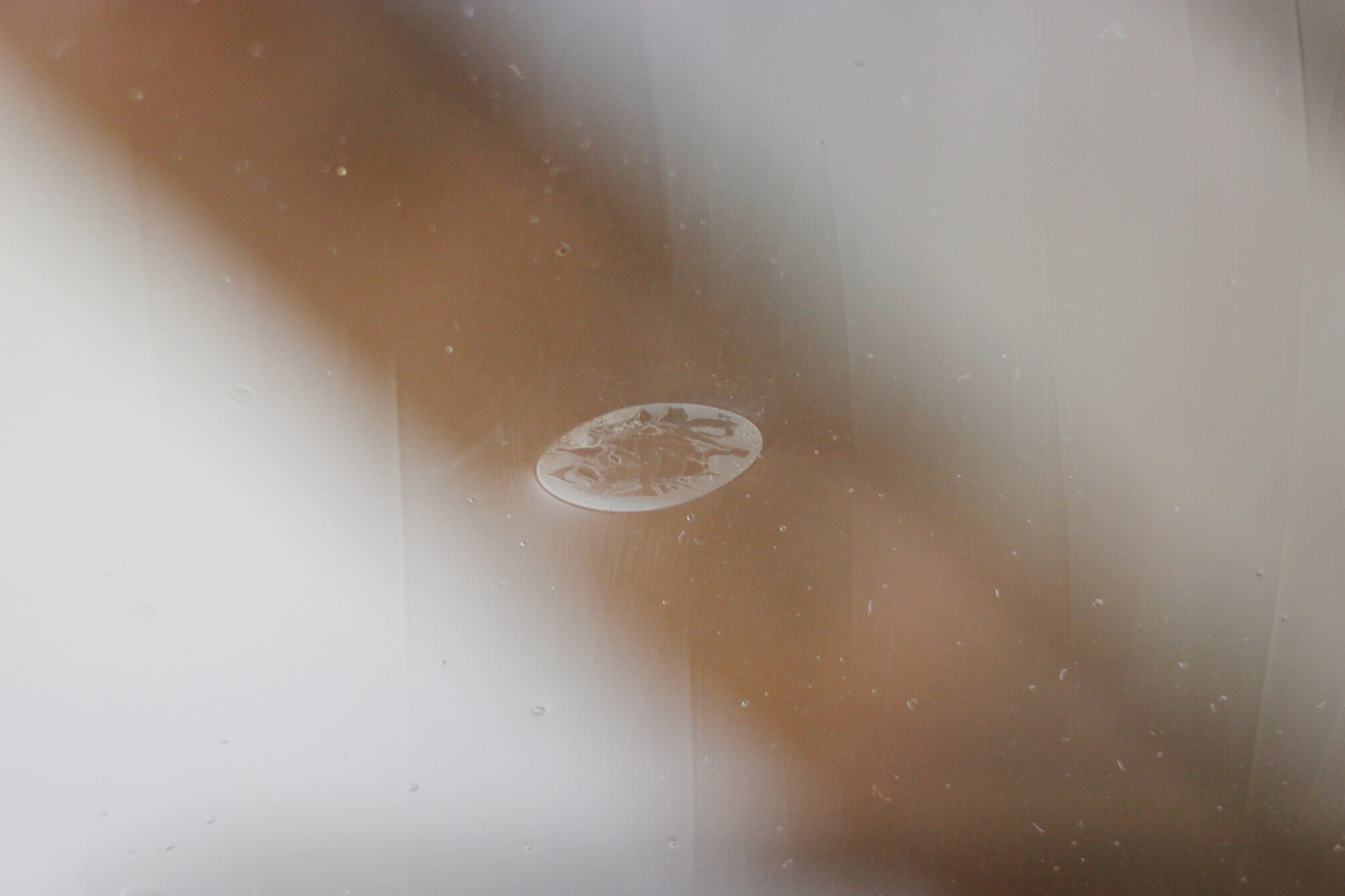

The door leading to the kitchen has a section in stained glass. The other day, I took a closer look at one of the spots on it, which I had half-consciously registered every time I passed it. On two square meters, there are three of them. All are oval in shape. Two of them seem to be flat bubbles of air, haphazardly produced during the manufacturing of the glass, I imagine. The third one, however, is peculiar. It drew my attention because it appeared to represent something. Upon closer investigation, it seemed to allude to different things. A model ship, like the ones in glass bottles. A dragon, like the one used on the Welsh national flag. A tailed, devilish figure riding a cloud-like motorcycle. What skills the glass worker must have had, to produce an image in a glass covered air capsule like this. I closed the door softly, as the microwave’s signal sounded.

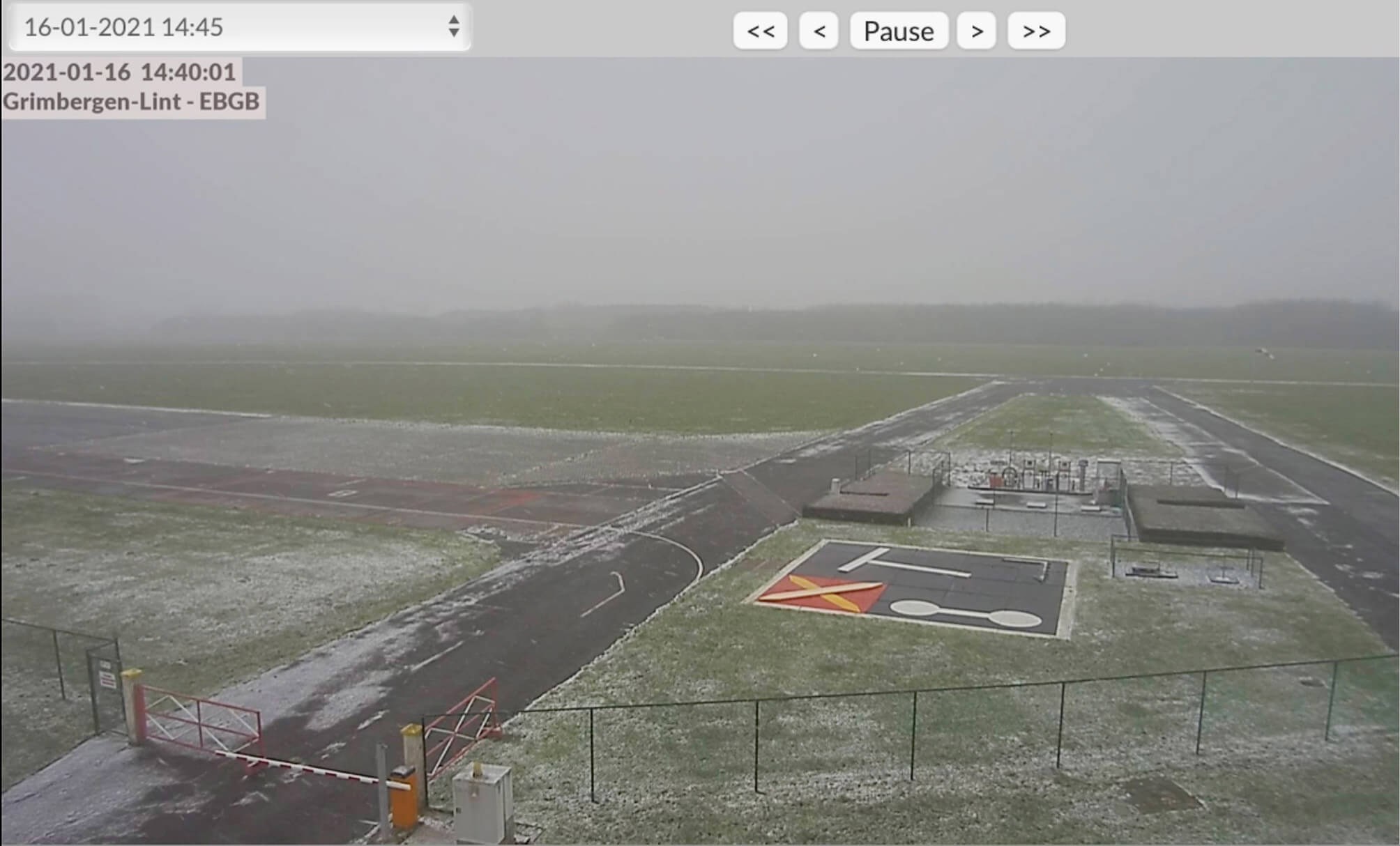

Recreational airfield at Grimbergen, webcam footage.

09:10:00The frame shows the first movement on the terrain. The gate has been opened, the barrier lowered. A black car is in the back. In the forefront, aviation signs on the ground: a yellow cross on a surface painted red; an arrow in a 90° angular shape; two circles connected by a line; a T-shaped line.

09:20:00Two men talking, each one on one side of the barrier. The man on the side of the airstrip has two dogs with him. The aviation signs have changed: the arrow is gone; the horizontal bar of the T-symbol has moved to the other side of the vertical line; one yellow line that made up the cross on the red surface is gone, leaving one yellow diagonal line.

10:09:01A small white aircraft (the two men and the dogs are gone).

10:20:01The aircraft in the same position, with what seems to be an open roof.

10:40:00Aircraft leaving the gas station where it was before.

11:10:01A white car at the gas station, where previously the aircraft was stationed; a silhouette of a man, perhaps.

11:30:01White car gone.

11:50:01Small white aircraft at the gas station; man in red jacket next to the aircraft. Not clear if it is the same aircraft seen in frame 10:09:01.

12:10:01Aircraft appears to be heading for take-off.

12:20:01Aircraft gone.

12:40:01White dots on the grass that appear to be birds.

14:10:00First precipitation: snow, visibility lessens.

14:20:00More snow, wind is stronger; someone has replaced the yellow stripe so that, again, a yellow cross is formed on the red background.

15:10:00The grass and the concrete get increasingly white. No aircrafts, vehicles or persons can be discerned. The aviation signs beneath the thin-layered snow are still visible, and unaltered.

Every so often architects ask me to photograph projects of theirs under a blanket of snow. Snow-days are rare around here. In an attempt to avoid a futile drive along roads in winter conditions, I check webcams near the project-to-be-photographed before setting out.

Webcam Grimbergen, meteobelgie.be: https://www.meteobelgie.be/waarnemingen/belgie/webcam/272/grimbergen

http://www.rvg.be

Until recently, for as long as I could remember, the packaging of Tabasco® Pepper Sauce had been unchanged. On the front of the packaging, there is a photograph of a bottle of Tabasco®, scale 1:1, against an orange background.As far as packaged goods go, this is a highly idiosyncratic and quirky example.

The background colour approximates the colour of the liquid inside the bottle, resulting in as good as no contrast. Moreover, as the image of the bottle is scale 1:1, the packaging becomes kind of unnecessary and superfluous, also because the life-sized image of the bottle is the only way information is given to the customer: there are no additional slogans, no repetition of the brand name, no props and no decor. The image of the bottle advertises the bottle. It seems to add nothing the bottle could not do by its own (like a bottle of wine does).

What makes the packaging truly stand out, however, is the fact that the image of the bottle is not positioned vertically, but is slightly askew. It seems to be the result of a design error, and has an amateur feel to it. The decision to keep it as such and not correct it up until today, is, however, a stroke of genius. The non-vertical positioning alters the relation of the image of the bottle to the bottle inside: as the box is standing on a shelf, the tilted image of the bottle undermines its representational superfluousness.

At the copyshop, on a shelf above photocopier 8, the lid of a box of paper serves as the container for ‘forgotten originals’.1

The book being copied: Didi-Huberman, G. La ressemblance par contact. Archéologie, anachronisme et modernité de l’empreinte. Paris: Les Editions de Minuit, 2008.

In his Handboek Varende Scheepsmodellen (Handbook Sailing Ship Models) André Veenstra explains the different classes in ship model-competitions. There’s a wide variety. For static ship models the most important one is ‘truth-to-nature’. A jury compares the model to photographs of the actual ship and brings into account categories such as amount of work, degree of difficulty, scale ratio, construction execution and painting.

The most interesting class – according to Veenstra – is F 6. In this particular class, a number of participants with different boats will form a team. Together, they will perform a certain ‘act’ with a maximum duration of ten minutes. During the act, they mimic a slice of reality. Such as, for example, ‘rescuing’ and towing a ship in distress; extinguishing a fire on a tanker or oil rig, lichen and/or tow the sunken wreckage to the harbor, stage a naval battle, etc.

Page 262 shows a photograph of such a mimicked slice of reality. The caption explains: ‘Image 14.15. The Dutch demonstration in the F 6 class during the European Championship of 1975: the oil rig is set on fire by a motorboat with terrorists. The fire is extinguished and the oil rig is quickly towed to a safe harbor by tugs. The show was performed by six people and took a very creditable fourth place.’

The torn off section of roofing on the grass has part of a text carved in it: ‘UDI’ and ‘EN’ are still legible. It must have come from another roof; the one shown in the photograph has no missing sections, nor visible repairs.

The roofing that is still on the garage shows a drawing of some kind. A floorplan for a squarish building with a supporting column along each side, or the layout for a tactical explanation, perhaps.

The road down from the top of Mount Vesuvius, at Atrio Del Cavallo. The sun sets. The last tourist bus has headed down. Then the headlights of the guardian’s car swing their way down. It must be freezing. I am holding an orange-sized piece of petrified lava, probably stemming from the 1872 or 1944 eruption. A kilometer further down the road, the old Observatory is empty. Nowadays, monitoring seismic changes is done in a research centre in the city of Naples. Their seismographic registrations can be followed online, in real time. Two headlights swirling along the slopes, underneath me, are coming upwards.

(‘Imaginary landscape in the actual greater Gent, some thousands of years ago. A grassy riparian zone separates rivers from the edge of the forests’)

Imagine a deserted city of Gent, overtaken by nature, Thiery asks the reader in his book Het woud (The Forest). After fifty years, you return to the city. Buildings have collapsed, streets are overgrown. It has become an impenetrable, dense forest, except for the river on which the reader makes his or her way through it. In the first half of the twentieth century, Leo Michel Thiery made one of Belgium’s first botanical gardens for educational purposes. In the middle of an industrialized quarter of the city of Gent, the garden presented different sceneries. There were landscapes from the Alps, dunes, the Ardennes, steppe. Besides sceneries with chalk-, loam-, marl- and sand-based vegetation, there were forests, grasslands and swamps.

After his death, Thiery’s garden decayed. Decades later, it was restored, with the Alps, dunes, the Ardennes and steppe now classified as a protected view.

Thiery, M. Het woud. Een proeve van plantenaardrijkskunde. Gent: De Garve, s.d., p. 14

I’m taking a scan of a family photo album given to me after my grandmother passed away, wanting to write something about the marvelous portraits inside. The genealogy is only partly clear to me: I recognize my dad as a kid, my uncle, my grandmother, her brother in the laboratory he (said he) ran. He smelled of cigars and severe perfume. The older photographs present people I don’t know, but must be my ancestors. My grandmother told me stories1 that, historically, reach further back than the figures I recognize in the photographs. There are no names and no dates in the album. The first two pictures seem to be the oldest ones.2 I retract them from the album pockets in which they were slid to check if something is written on the backside. When I take the album away from the scanner’s glass plate, particles of leather, gold varnish and sturdy cardboard come loose. I place a sheet of paper on the glass plate and press ‘scan’ again.

Once she (my grandmother) went home from school, sick, with her bicycle. She studied to become a nurse. The school was in Brussels, about 60 kilometers from her native village M. The milkman’s van tipping over in front of my grandmother’s parental house. A milk covered street. My great-grandfather, physician and mayor at M. Something happened during the Second World War having to do with telephones or radios when she was still a kid.

I must have driven past this rocky landscape about sixteen times, going back and forth between viewpoints and the house the parents of a friend let me stay in. On the last day, I left early for the airport, pulled into a lay-by, took my tripod and camera out of the trunk of the red Volkswagen Polo rental car and made two photographs.1 It was only when I got home, had the film developed, scanned it and was removing dust particles from the file, that I discovered the hand painted text on the rock: ‘PROIBIDO BUSCAR SETAS’.

Fred from Zwolle offers two Sparta K-10s on Marktplaats.nl on 29 September 2022. The asking price for the two bikes is 250 euros, bids may start from 200 euros. The green bike has a front light that is powered by a rim dynamo, while in another photo we see a front light on the orange bike that is presumably battery-powered, as may be the case for the rear lights. The carrier mounted at the front of the green bike is clearly a luggage carrier, as is the one at the back. What the carrier mounted at the front of the orange bike is for, is unclear. The description of the bikes does mention the function of the loop protruding from the frame at the back of the Sparta K-10:

‘20-inch bikes that we have always used while camping. No gears but smooth and light pedalling. Ideal for running small errands close by or a quick errand in the toilet building. They are light and quite short making them easy to take on the train. Ideal as a short-distance bike between station and work. Both are, furthermore, in good condition. Each bike comes with a key for the integrated cable lock. Are listed as a ladies’ bike but I (male) get on just fine.’1

’20 inch fietsen die wij altijd tijdens het kamperen hebben gebruikt. Geen versnellingen maar soepel en licht trappend. Ideaal om kleine boodschappen dichtbij te doen of een snelle boodschap in het toilet gebouw. Ze zijn licht en vrij kort waardoor ze makkelijk mee te nemen zijn in de trein. Ideaal als korte afstandfiets tussen station en werk. Beiden zijn verder in goede staat. Van elke fiets beide sleutels aanwezig voorzien van een geïntegreerd kabelslot.Worden als damesfiets genoemd maar ik (man) kom er prima mee vooruit.’

Lars Kwakkenbos lives and works in Brussels and Ghent (B). He teaches at KASK & Conservatorium in Ghent, where he is currently working on the research project ‘On Instructing Photography’ (2023-2024), together with Michiel and Arnout De Cleene.

Robert Nemiroff and Jerry Bonnell’s lesser known project (R.N. and J.B. being the creators of Astronomy Picture of The Day), was making websites containing over a million of digits of square roots of irrational numbers, e.g. seven. ‘They were computed during spare time on a VAX alpha class machine over the course of a weekend. […] We believe these are the most digits ever computed for the square root of seven on or before 1 April 1994.’ Elsewhere, R.N. states: ‘They are not copyrighted and we do not think it is legally justifiable to copyright such a basic thing as the digits of a commonly used irrational number.’ If one wanted to get a copy of the 10 million digits of the square root of the number e R.N. and J.B. computed in their spare time, one can send an email to R.N. at nemiroff@grossc.gsfc.nasa.gov.

https://apod.nasa.gov/htmltest/gifcity/sqrt7.1mil

https://apod.nasa.gov/htmltest/rjn_dig.html

https://apod.nasa.gov/htmltest/rjn.html

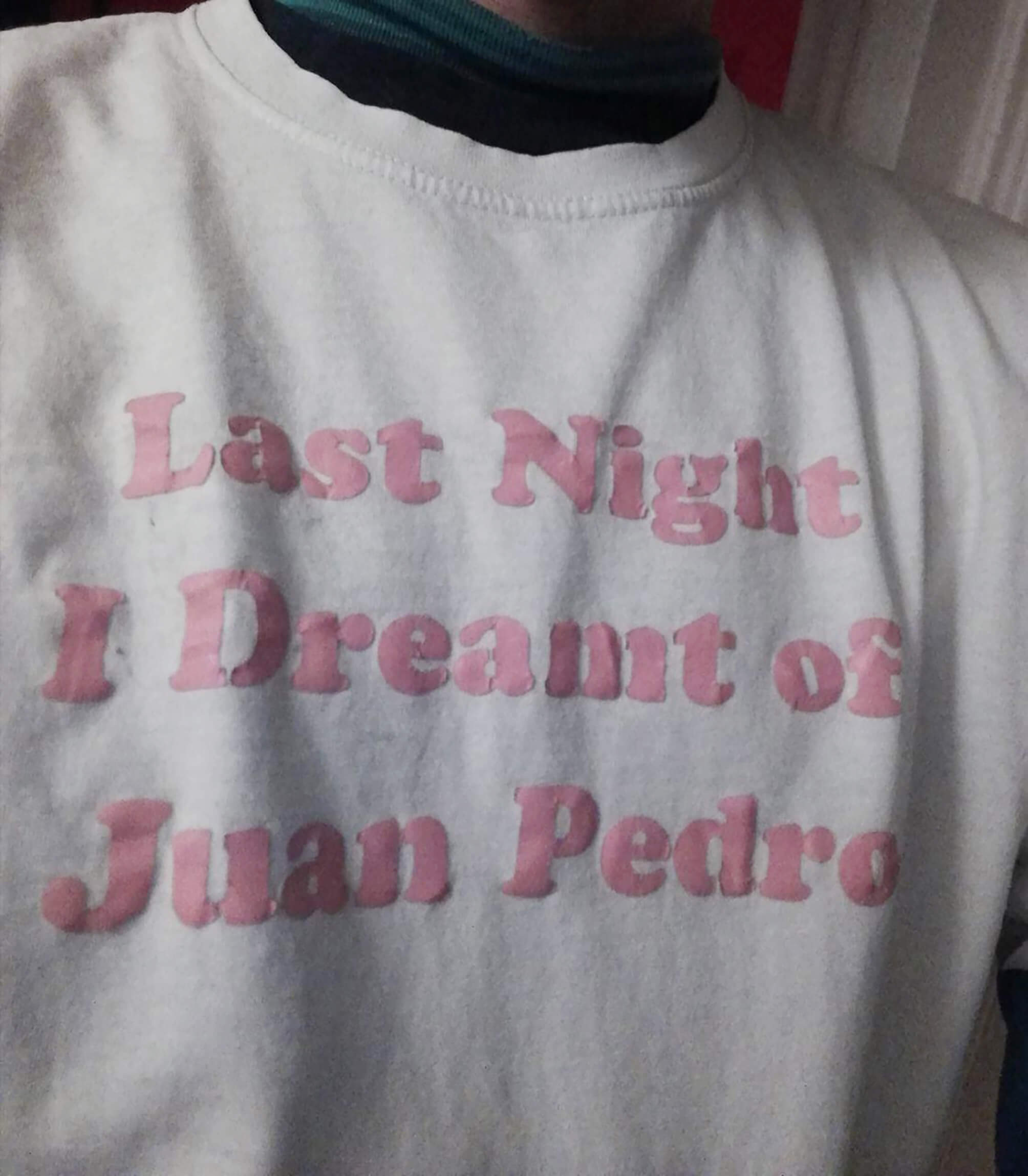

While I was sitting in the laundromat one evening waiting for my laundry to finish its cycle, La Isla Bonita by Madonna came on the radio. Competing with the rustle of seven rotating laundry machines, the song reminded me of a T-shirt that was now being washed.

The short phrase in the song’s lyrics ‘last night I dreamt of San Pedro’ would nestle itself somewhere in the back of my head and bubble up every now and again for no particular reason. I made this shirt for the occasion of Valentine’s Day in 2019 to commemorate my friendship with Jan-Pieter. I remember once mumbling the lyrics to La Isla Bonita, replacing ‘San Pedro’ for ‘Juan Pedro’, forgetting it for some time and then a while later printing it on a T-shirt.

Tjobo Kho is a graphic designer and publisher based in Amsterdam. Since 2017 part of the floating collective and publishing platform OUTLINE, and recently started his own publishing house no kiss?.

It has been snowing. A black BMW is parked on the other side of the street and is cut in half by the separation between negatives 4 and 5. Apart from a slight kink in the landscape, the negative on the right is a perfect continuation of the one on the left. The fence around the orchard, the branches of the apple tree and the power lines connect implicitly in the void between the negatives.

Based on De Cleene De Cleene, The Situation as it Is. A Photonovel in Three Movements (APE, 2022).

At the beach of Cap d’Antifer in Normandy one can find ‘sea glass’ between the pebbles: pieces of broken glass that have naturally weathered by being tumbled by the ocean, over and over. Sharp edges and smooth surfaces vanish. The historical origin of the glass pebbles (glass bottles, a shipwreck) erodes. Only the colour of the pebbles gives an indication of their history, be it vaguely. Varieties of green sea glass are common, but other colours, such as red (Shlitz beer bottles) or yellow (interbellum Vaseline containers), are more rare and have to be sought after attentively.

It’s 4.15 PM. The tide is pushing three people towards the cliffs.

At the copyshop, on a shelf above photocopier 8, the lid of a box of paper serves as the container for ‘forgotten originals’.1

The book being copied: Didi-Huberman, G. La ressemblance par contact. Archéologie, anachronisme et modernité de l’empreinte. Paris: Les Editions de Minuit, 2008.

At the beach of Cap d’Antifer in Normandy one can find ‘sea glass’ between the pebbles: pieces of broken glass that have naturally weathered by being tumbled by the ocean, over and over. Sharp edges and smooth surfaces vanish. The historical origin of the glass pebbles (glass bottles, a shipwreck) erodes. Only the colour of the pebbles gives an indication of their history, be it vaguely. Varieties of green sea glass are common, but other colours, such as red (Shlitz beer bottles) or yellow (interbellum Vaseline containers), are more rare and have to be sought after attentively.

It’s 4.15 PM. The tide is pushing three people towards the cliffs.

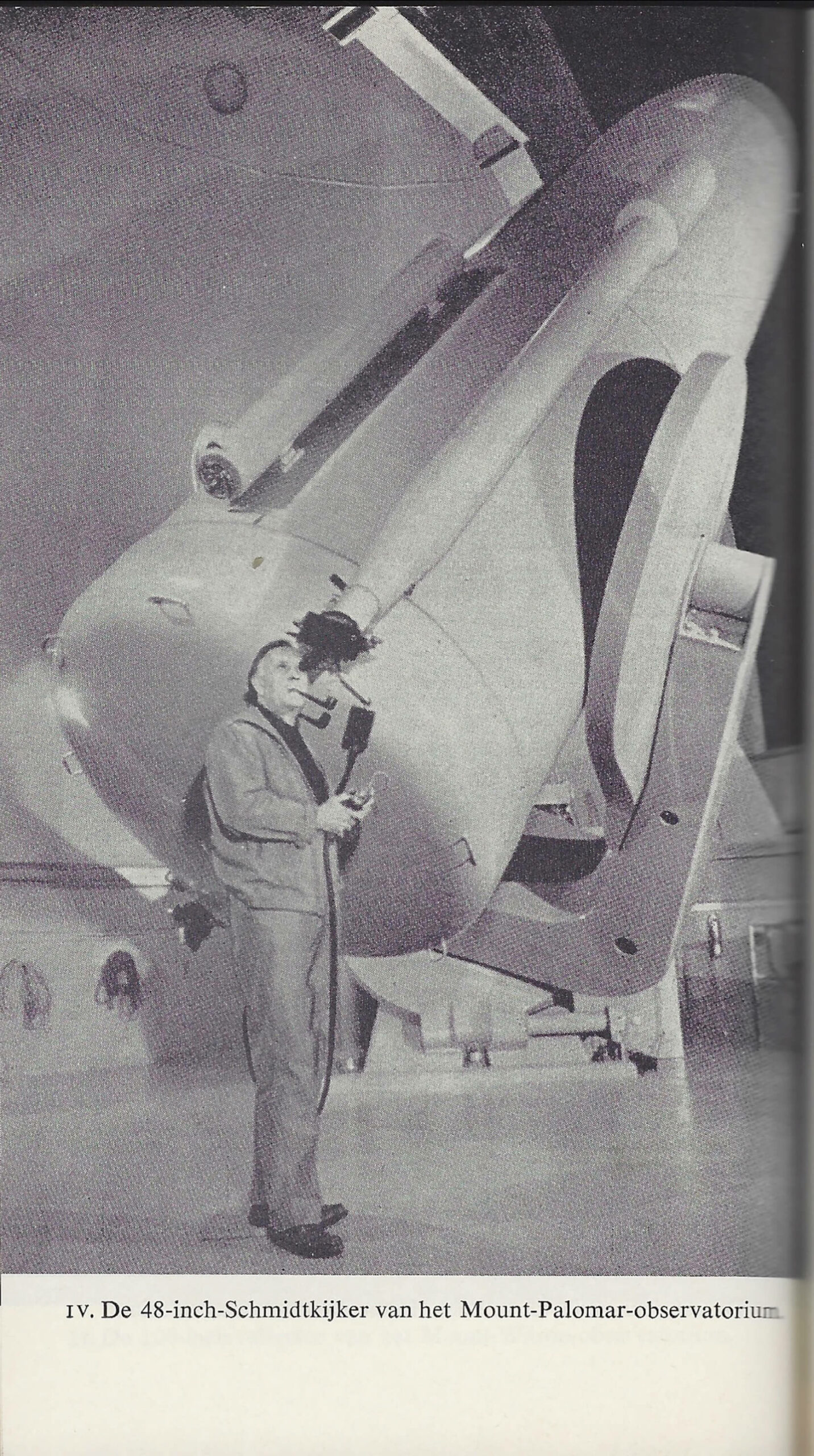

The 48-inch Oschin Schmidt, a renowned reflecting telescope at Palomar Observatory, California, was used for the Palomar Observatory Sky Survey (POSS), published in 1958, one of the largest photographic surveys of the night sky.

Based on the man’s pipe shadow’s direction, thrown onto the telescope, there is reason to believe an off-camera flash was used to make the picture.

At the copyshop, on a shelf above photocopier 8, the lid of a box of paper serves as the container for ‘forgotten originals’.1

The book being copied: Didi-Huberman, G. La ressemblance par contact. Archéologie, anachronisme et modernité de l’empreinte. Paris: Les Editions de Minuit, 2008.